144 - NASA-1 - Comrades and Cognac (Thagard on Mir)

Table of Contents

Norm Thagard is about to become America’s first Cosmonaut. What challenges will he encounter during his four months on the Russian space station Mir? And why are they bringing so much juice?

Episode Audio #

Photos #

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 144, NASA-1: Comrades and Cognac

Last time, we rode along with Space Shuttle Atlantis and watched as a distant point of light grew into the cluster of solar arrays and pressurized cylinders that the Russians called Mir. When the orbiter nudged up against the docking port on the Russian space station, the result was the largest spaceborne structure and largest orbiting crew in history up to that point. Among STS-71’s many goals was the delivery of the EO-19 crew to Mir, and the retrieval of the EO-18 crew, including American Norm Thagard. In that episode, we saw the last few days of Thagard’s remarkable four months in space. Today, we’ll get the rest of the story.

Before we really get into Thagard’s flight, I feel like I have to clear the air about something. In the past, I have said some pretty unkind things about the Russian space program, usually when explaining why I had no interest in covering their side of the space race. In the 100th episode Q&A special I went so far as to say that I quote “don’t have a ton of respect for their space program in those days.” referring roughly to the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. Well, I’d like to say right now that while I still am not at all impressed by Russia’s consistent track record of scrambling half-baked plans into action in order to snag some arbitrary space record away from the United States, my comments were probably taking things too far. Stuffing three guys into a Voskhod spacecraft without pressure suits or going out of their way to claim the “first woman to perform an EVA” record before Kathy Sullivan is not cool. But what is cool is Russia’s remarkable series of long duration space stations. Through a combination of technological innovation, a lot of trial and error, and plain old Russian tenacity and grit, our friends to the east set the standard in long duration spaceflight. And as I familiarized myself with the Mir project over the last few months, my admiration for Russia’s space stations has only grown. Coming from the NASA side of things, some of the stories we will hear about Mir will surprise and occasionally shock us. But the fact is that Russia quietly kept this mass of hardware running and doing its job year after year, crisis after crisis, far longer than any of it was intended to last, and at a fraction of the cost of NASA operations. I’ve really come to admire the spirit perhaps best expressed by fictional cosmonaut Lev Andropov when he said “this is how we fix things on Russian space station” before repeatedly bashing critical hardware with a wrench.

With that out of the way, let’s take an extremely brief tour through Mir’s history. I might do a more fleshed out version of this down the road, and probably would have made sense to do it before introducing Mir at all but, well, time makes fools of us all.

Mir came after a long line of Soviet space stations, which flew under the name “Salyut”, which as you may have guessed, just translates to “Salute”. Given the background that we already have with the Shuttle, you can kind of think of these stations as being like Spacelab, the European laboratory that frequently rides in the back of the orbiter. The difference, of course, is that Salyut would stay in space for months or years at a time, carrying their own systems for power, propulsion, communication, et cetera. Soviet crews would launch in their Soyuz capsules, dock with the stations, and go about their work onboard. Regular flights of the Progress resupply vehicles would ensure that the crews had food and water, new scientific gear, and propellant for the station. These missions were largely successful, and gave Russia a ton of experience with the physiological effects of long duration spaceflight, as well as shifting priorities and repairing things on the fly.

On February 20th, 1986, the core of a new type of space station was launched atop a Proton rocket. The station was called “Mir”, which can be translated to “peace” or “world” or “village”. But Clay Morgan’s book on the Shuttle-Mir program points out that it has a deeper connotation, since the word “mir” was used for the 19th century Russian peasant communities that owned the land.

What made Mir different was that it was designed to be modular. One of its two longitudinal docking ports was replaced by a five port node. You can imagine this as a cube with a docking port on each side. Only five ports, not six, because one is built into the station itself. So there was still a longitudinal port, lined up along the length of the station, as well as four radial ports sticking out to the sides. This would allow multiple modules to be launched and connected over time.

Just as one quick side note that’s too weird and interesting to skip.. at the time that Mir was just getting started, Russia was still operating the aging Salyut 7 station. In a unique operation, Mir’s first crew climbed into their Soyuz spacecraft, undocked, puttered over to Salyut 7, grabbed a whole bunch of useful stuff like spacesuits and computers, and brought it back to Mir. Station to station! In fact, one of those computers went home on Atlantis on STS-71. So it went from Baikonur to Salyut 7 to a Soyuz to Mir to Atlantis and back down to Earth.

Anyway, skipping ahead to 1995 (see I told you it’d be a brief history) there are four modules. At the heart of everything is the base block, which was launched in 1986.

On the back of the base block is Kvant, which translates to “Quantum.” It contains some science instruments, a docking port, and oxygen generation systems. It also contains some gyrodines, which are similar to the control moment gyros we know from Skylab, allowing the crew to point the space station without using thrusters.

Sticking out of two of the radial docking ports on the front of the base block were another two modules, Kvant 2 and Kristall. Kvant 2 included more science gear and more gyrodines, among other things. It also included a dedicated airlock, so crews no longer had to vent the entire station to head outside. Kristall, which just means “Crystal” completes the picture for now, and added some materials processing and other science capabilities to the station. The resulting station sort of looks like a capital T flying through space, but with a bunch of solar arrays sticking out of it all over the place.

As we’ve discussed in previous episodes, the Shuttle-Mir program started to take shape in the early 1990s, but as soon as it came together it began to evolve. Originally the plan was just to fly a single astronaut on Mir, a single cosmonaut on the Shuttle, and complete a single docking. But it soon expanded into a seven astronaut program with NASA paying for additional Mir modules and flying a number of docking missions. In fact, thanks to the shifting nature of this program I might not even have the name quite right. It seems that it started as Shuttle-Mir but soon evolved to “Phase One” or maybe “the “NASA-Mir Program”. I’m just going to mostly stick with “Shuttle-Mir” since it’s the most descriptive.

It was under that original limited program that veteran shuttle astronaut Norm Thagard first got involved. And while things later improved, it seems clear to me that NASA’s initial involvement with the Mir program was a little.. scattered. In a 1998 oral history that I will be drawing from a lot in this episode, Thagard recalled how the initial Russian language training consisted of hiring a Russian woman who lived in Houston to swing by the center for an hour or two a week. I’m sure that helped, but he was never going to gain fluency that way. When he eventually did get support to attend the Monterey language institute, Thagard didn’t even get any transportation funding and had to drive his own car the nearly 2000 miles from Houston to Monterey. And then a wheel fell off the car in Death Valley.

Thagard eventually made his way over to Star City, Russia, home of the Russian space program. There he would spend a year training on the Soyuz and Mir systems, a process that normally took two full years. Joining him were a few NASA support staff, as well as his backup for the mission, Bonnie Dunbar. Dunbar was selected as backup thanks to her extensive knowledge of the payloads and science operations, but she struggled with the Russian language. Thagard mentioned the difficulty of focusing on lectures in Russian while trying to tune out Dunbar’s interpreter speaking English just across the room.

One of Thagard’s goals with this flight was to truly become a Cosmonaut. While he would bring valuable insight thanks to his experience on NASA missions, he didn’t want to insulate himself in a bubble of American culture. He lived in a Russian apartment in the same building as the other cosmonauts. After several months, his wife and son moved to Star City with him. His wife became a teacher at a nearby school, and his son attended a Russian high school. I have to imagine that this attitude helped Thagard to better integrate with his crew, which is a key metric noted by the Russian space program. With a week long shuttle mission, unless two crew members are literally strangling each other, if there is friction they can generally grit their teeth, be professionals, and get through it. But on a multi-month long mission, with long stretches of time without communications, it was really important that a crew got along.

And while the American and Russian space training programs were more similar than not, that wasn’t the only difference. One notable difference was that crews would be subjected to oral exams, where experts in various subsystems would quiz them, looking for holes in their knowledge. This was especially daunting to the American crew members since the tests were conducted entirely in Russian. This is probably why Thagard said that while he wasn’t exactly fluent in Russian and would struggle with a typical conversation, he was an expert in technical Russian. In fact, several of the instructors joked that the Americans often did better on the tests than the Russians, since they took the tests so seriously.

After a year of living and working in Russia, launch day was soon upon Mir’s next crew, so I think it’s time to meet them. This also means that it’s time for the latest episode of “JP struggles to pronounce Russian words”

The Soyuz spacecraft isn’t reused, but they still get some spiffy names to use as a radio call sign. So today’s Soyuz, Soyuz TM-21, also went by the name Uragan, or “hurricane.”

Commanding the Principal Expedition 18, or EO-18, mission and sitting in the left seat of the Uragan Soyuz was spaceflight rookie Vladimir Dezhurov. Vladimir Nikolaevich Dezhurov was born on July 30th, 1962 in the Yavas settlement in Mordovia, Russia. He graduated from the S.I. Gritsevits Kharkov Higher Military Aviation School before heading off to join the Soviet Union’s Air Force. He was selected as a cosmonaut in 1987 and this is his first of two lengthy spaceflights.

Sitting in the middle seat on the Soyuz was Flight Engineer Gennady Strekalov. Gennady Mikhailovich Strekalov was born on October 26th, 1940, in the Mytishohi mit-show-hee Moscow region of Russia. In 1965 he graduated from the N.E. Bauman Moscow Higher Technical School as an engineer, joining RSC Energia to work on space missions. Actually I’m pretty sure that back then Strekalov actually joined a design bureau which eventually morphed into Energia.. it’s kind of confusing and I didn’t bother running it down. He was selected as a cosmonaut in 1974 and began training as a flight engineer. He flew on several missions of varying length, including a dramatic pad abort using the launch escape system when his Soyuz rocket blew up on the pad in 1983. Alongside him was Vladimir Titov who we talked about a few missions back. Not counting the pad abort, this is his fifth and out of five flights.

And finally, our Research Cosmonaut, Norm Thagard. We know Thagard from STS-7, STS-51B, STS-30, STS-42, and now Soyuz TM-21 / EO-18, his fifth and final flight.

A few days before the March 14th, 1995 launch date, Dezhurov, Strekalov, and Thagard traveled to the Baikonur Cosmodrome in the former Soviet state of Kazakhstan to make their final preparations before heading to space. In a lot of ways, this process is pretty similar to the process over on this side of the planet. The crew entered into quarantine, limiting their exposure to spouses and necessary personnel only. One tradition in the final days leading up to launch involved the crew throwing a party for all of the support people who had helped to make the flight happen. Among the party supplies were a few cases of cognac, a type of brandy, for the guests to enjoy. OK, sounds like any launch party so far. What’s different came after the party. Not all of the cognac was gone after the party. So a couple of days before the launch, Dezhurov, Strekalov, Thagard, and their Soyuz instructor met in Commander Dezhurov’s room and carefully transferred the remaining cognac into one liter plastic bottles normally used to transfer chemicals. After being thoroughly taped up, the bottles were innocuously labeled with the Russian word for “juice.” before being loaded onto the Soyuz. Ohhh-kay.. oh! I see. They’re carrying the, uh, “juice” into space to bring back as a fun space-flown libation, right? Well, not quite. As Thagard put it “they don’t bring anything back”, but more on that later.

On launch day itself, preparations were largely similar to what Thagard had experienced before. One difference was that since it was expected to take two days to get to Mir, flying in the somewhat cramped Soyuz, extra steps were taken to ensure that the crew wouldn’t need to avail themselves of the facilities. After that, they suited up with assistance from suit technicians, did their final checks, and began to make their way outside. Continuing with the quarantine, they limited their exposure to essential personnel, and those they did meet disinfected their hands first. Though Thagard noted he thought it was funny that the crew were also required to disinfect their hands before interacting.

Then, the crew headed outside and stopped in front of the general who commands the base, and stood at attention. Commander Dezhurov saluted the general and said that the crew were ready to fly, and the general gave them permission to fly. And then, despite all of the quarantine precautions I just talked about, the crew proceeded to push through a big crowd of people just standing around at this ceremony with the general. Thagard said they were literally rubbing shoulders with people as they made their way to the bus to be taken to the pad. So much for quarantine.

On the way to the pad, we encounter another tradition dating all the way back to the very first human spaceflight. It seems that while driving out to his Vostok spacecraft, Yuri Gagarin had to pee. So unlike Alan Shepard, he stopped the bus, got out, and for some reason peed right there on the rear tire of the van. Gagarin’s flight went off without a hitch, so it has been a staple of the crews that followed him to repeat the act. If you’re curious, at least one woman cosmonaut collected some urine in a vial ahead of time, just to pour out on the tire at this moment. Anything for the mission, I guess. For the record, Thagard, noting the frigid temperatures, wide open spaces, and broad daylight, declined.

OK, well, that was weird. But whatever, back on the bus. After a few minutes of driving, the bus pulls up at the launchpad and the crew gets out, only to encounter another big crowd just sort of milling about. This is especially bizarre because now they’re right next to a fully fueled orbital-class launch vehicle! The crew pushed through the crowd again and walked up the stairs to the elevator, and were soon aboard their spacecraft.

Once on board, Thagard’s duties for the launch were fairly limited. His main job was to follow a schedule and occasionally switch which onboard camera was being broadcast to the rest of the world. Eventually the crowd outside dispersed, the countdown hit zero, and on March 14th, 1995, at 11:11 am, the Soyuz rocket carrying the Soyuz spacecraft lifted off. An American was launching from the same pad that Yuri Gagarin had only 34 years earlier.

Thagard said that the uneventful ascent was not unpleasant. Compared to the shuttle, it had a much smoother early flight thanks to the lack of solid rocket boosters, but a somewhat bumpier later flight, and overall lacked the same sensation of power that the shuttle gives. Once they were safely on orbit, Thagard was able to look out the window, and became the first American to see a solar array attached to his spacecraft. Well.. I guess other than the nine guys who flew on Skylab. Oh, and I guess other than the crew of STS-41D, who extended that big solar array in the payload bay. You know what, never mind.

The crew settled in for the two days of maneuvering and coasting required to approach Mir. The descent stage of the Soyuz is pretty cramped, but the orbital module, or living module, had significantly more room, allowing the crew to sit around enjoy meals together. And the smaller accommodations actually came with a benefit. Thagard was a frequent sufferer of space adaptation syndrome. On this flight he had gone so far as to have an intravenous line inserted so he could quickly and easily give himself a dose of anti-nausea meds, something his Soyuz commander wasn’t wild about. But once he got up there, he found that the smaller spacecraft lead to less floating around and smaller head movements, and he never actually got sick, just a little “stomach aware”. By the time they got to the more spacious Mir, it had already been two days and his body had adapted. Thagard wondered if this was the true cause behind Russia’s boasting that their cosmonauts rarely get space sick.

After docking with Mir, the old crew welcomed the new one and began to show them around. The two crews would have nearly a week of overlap time before the old crew headed home, and it was a critical period. With Mir already nine years old, the station was a little lived-in. Over the years, the ground’s idea of what the state of everything was up there had drifted, and could no longer be relied upon. Instead, the old crew simply showed the new crew where everything was. One of the old crew members was especially excited to see the new crew because it meant it was almost time to go home. Valeri Paryakov had already been living on the station for more than an entire year. When he eventually returned home, it was after an incredible 437 days in space, a record that stands to this day. He was in good shape but was more than ready to stand on solid ground again.

As they settled in, a couple of minor cultural differences emerged that I think were more interesting than problematic. Thagard noted that his young commander suddenly became a little more authoritarian, ordering his crewmates around. Thagard’s speculation, which I’ll convey as just that, his speculation, was that Dezhurov may have been acutely aware that this was his first flight while it was the fifth for both Strekalov and Thagard, and may have felt the need to be a little more assertive. After a few days, Strekalov would push back, shouting and causing the commander to back off. Thagard figured that was just how things were done and followed suit, leveling a blast at his commander whenever things got too tense. He was apparently right since the crew ended up working well together and remained good friends.

For Thagard, the early part of the mission was dominated by getting started with the 28 different experiments that had been flown up for him. And since it’s not like it’s possible to call a repair person, when the one freezer on board started acting up, Thagard also spent many hours attempting to repair it. The freezer was important since it was used to store biological samples. After a few weeks, it finally failed entirely and a number of samples were lost. This was a bummer all on its own, but it also meant that suddenly Thagard didn’t have a ton to do. A lot of his work was planned to take place on the Spektr module.. but that was delayed and hadn’t launched yet. And now with no freezer, there was no point in doing biological experiments. Thagard became one of the few people to become truly bored in space. He claims that even the view out the window eventually got old, which surprises me, but I wasn’t the one there. Thagard’s wife tried to help out by sending up a book of crossword puzzles, but since his Russian crewmates had the opposite problem and were extremely overworked, he couldn’t bring himself to lounge about solving puzzles while they struggled.

One thing he did to pass the time was to take a bunch of photos. But Commander Dezhurov, perhaps channeling a little bit of the old Cold War paranoia, didn’t want him to take too many. That changed when a resupply vehicle arrived carrying, among other things, a whole bunch of film for Thagard. Dezhurov apparently figured that if the ground had allowed all this film to be sent to them, they must be OK with Thagard taking photos.

As the days tick by, we come to one of the first serious problems that Thagard encountered during his long stay on Mir: poor communications. In the previous episode I stated that Russia didn’t have a geostationary communications network similar to TDRSS. This isn’t quite right. Russia does have one but it belongs to the military, and if I’m understanding correctly, the Russian space agency needs to pay to use the system. Since they’re always strapped for cash, they use it as little as possible. This restricts communications to passes over ground stations. But since those ground stations are mostly in Russia, it’s fairly limited. On some days there would be as little as 42 minutes of communication with the ground. Total. Over 24 hours. And in those 42 minutes, a lot of critical stuff had to be conveyed. Thagard’s work was important but it wasn’t critical to the operation of the station, so was often a lower priority. This resulted in several instances of Thagard not speaking with mission control at all for as long as three days in a row.

This lack of communication was a problem psychologically but not necessarily in the way that you might expect. Thagard just wasn’t looking to chat. After all, he was still able to have weekly conversations with his family via the satellite link. But he was a driven astronaut trying to get a job done. When he couldn’t seek guidance about procedures that didn’t work or couldn’t report unexpected problems it meant that he couldn’t work, which really bothered him.

Still though, a little more human contact would be nice, so his Russian crewmates suggested he make use of the amateur radio on board but Thagard pointed out that he didn’t have a license. They said that anyone on Mir is authorized to use their radio. So Thagard shrugged and hoped the FCC didn’t have any ground to space missiles and made a number of contacts with hams on the ground.

A couple of times now I’ve mentioned a resupply ship bringing stuff up to the crew. There was actually just the one, Progress M-27, which docked with Mir a few weeks into the mission. The Progress is basically a Soyuz but without the capability to survive reentry. That added extra capability for carrying cargo and provided a handy way to get rid of trash. Simply fill Progress with garbage and send it off to burn up over the ocean.

A Progress docking is completely automated and pretty routine. But as we’ll see down the road, it still presents a potential hazard. With that in mind, Dezhurov asked Thagard to wait closer to the Soyuz in case there was an emergency and they had to evacuate. But he said it was fine if Thagard wanted to take photos of the early part of the docking from a different part of the station. Thagard got a little caught up in the photos and suddenly realized that the docking was imminent. He scrambled to get to where he was supposed to be and in the process flew right through the node that the Progress was docking with. So at the moment of contact he was only a few feet away and could actually hear it connecting. As he put it “So I sort of blew that, but I got some good pictures of it.”

Among the many items being disposed of in the Progress was a shower that was installed in the Kvant-2 module. Much like the Skylab crews, the Mir crews found that a shower wasn’t actually all that useful or necessary in space, so the shower wasn’t used. In order to fit it into the Progress spacecraft more efficiently, the crew chopped it up.. using a machete. So now you know that for some reason, there was a machete on Mir.

As we approach the halfway point in the mission, we encounter another problem. NASA was still figuring out how to manage this whole situation, with Thagard’s job largely being to figure out the things they didn’t know they didn’t know. So sometimes things got missed. One thing that got missed was a strict diet experiment. When they arrived at the station, Thagard found out that NASA wanted the crew to meticulously log everything they ate and drank.. for the entire mission. OK, no big deal, except that Mir had two different stashes of food. One was a standard set of meals that repeated every six days, and the other was just sort of a general pantry with some extra stuff. Typically a crew would eat their standard meals and then supplement that with whatever they liked from the extra food. The problem here was that only the standard food had bar codes, and that was how they had to log their food.

The Russians wandered off of the diet plan fairly quickly, but Thagard was determined to stick with it. This is impressive because the food sounded pretty unappetizing, especially for someone like Thagard who is not a fan of fish. Unlike the American program, the food was not built around the preferences of the crew, and was just a standard six day set of meals, over and over again. And for four of those six days, the main entree was canned fish. The crew traded, with the Russians taking extra fish and Thagard taking extra asparagus, but that could only go so far. And come to think of it, it seems like that sort of violates the rules of the experiment, but that’s besides the point. With his miserable food situation, Thagard quickly began losing weight.

Every three days, as part of their medical tests, the crew would measure their mass using an onboard instrument. The resulting mass would be relayed down to the ground to be recorded. Despite being well aware of what the situation was doing to his body, Thagard decided to let it ride. He was curious how much weight he would have to lose until somebody on the ground noticed and intervened. The answer turns out to be six weeks, with the astronaut ultimately losing seventeen and a half pounds, just shy of eight kilograms. When the ground realized what was going on they told Thagard to eat anything on board other than his crewmates. But, as one last little irritation, they asked him to keep a paper log of what he was eating from the supplemental food. Thagard pointed out that that wasn’t really possible. There was so little paper on board that the crew was sketching out EVA plans on the lid of an opened food can, but they asked him to try anyway. Oh well.

Adding to the weight loss was a rigorous exercise regimen. Exercising in space is important, especially on a long duration mission. Thagard was determined to walk out of the shuttle under his own power, so he kept up with his workouts. One day he was exercising with a Russian apparatus that involved him looping some large elastic bands over his feet and stretching. One of these elastics slipped off his foot and rocketed right into his eyeball. The resulting blurred vision and pain when exposed to light made Thagard worried that he had seriously injured it. After patching it up, he was eventually able to speak with an ophthalmologist on the ground, who suspected that the eyelid had become inflamed and instructed him to use some steroid drops, which did the trick. Within a few days his vision was back to normal. Though I had to laugh when in the immediate aftermath of the accident, Strekalov asked what had happened. Thagard explained and Strekalov said “Oh, yes. Those things are dangerous. That’s why I don’t use them.” to which Thagard could only wryly respond “Thanks, Gennady, for the heads up on that one.”

One last little story at Thagard’s expense and then it’ll all be good news from here on out. As the mission was winding down, the Russian crew were asked to draw some blood samples so the impacts of the long duration flight could be studied. Since Thagard was a medical doctor, he was asked to draw the blood. No big deal, except to preserve the blood, specific vials with specific chemicals in them needed to be used.. and the crew couldn’t find them. Thagard spent most of a day going over the procedure and gathering equipment, eventually asking the ground for help with finding the vials. The ground asked the previous crew for suggestions and they told Thagard to look behind a particular wall panel, where he found a pile of white plastic bags full of equipment. He pointed out that quote “In some cases someone had actually written in black marker on the bag what its contents were, and in some cases those actually were the contents of the bag”. He eventually gave up and grabbed the needed vials from the American medical supply kit and finally went to draw the blood.. and Strekalov decided he didn’t want to do it. So Thagard turned to Dezhurov.. who says that if Strekalov didn’t want to do it then he didn’t want to do it. An exasperated Thagard eventually just asked the Russians to draw his blood so at least there’d be something to show for the exercise.

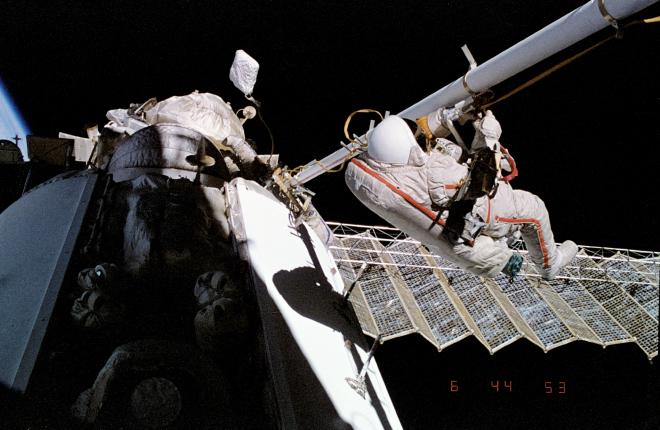

Alright, I promised things would be looking up for Thagard, and indeed they were. In May, the crew spent some time reconfiguring the layout of the space station modules. This reconfiguration required several EVAs which Thagard supported from inside, but is a pretty impressive capability of Mir that I’ll have to explain on another day. The goal was to make room for the new American-funded science module: Spetkr, which translates to “Spectrum.” On June 1st, with a little more than a month left in the mission, the Spektr module successfully launched and docked with Mir, suddenly providing a whole bunch of welcome work for the NASA astronaut. Thagard spent much of his remaining time configuring the module for science operations and actually performing science there. And a busy astronaut is a happy astronaut. I thought it was neat that the crew noted that the air inside Spektr and the Progress smelled notably different. It wasn’t especially good or bad, just different. Fresh Baikonur air.

There are a few major differences between a shuttle mission and a long duration flight like this. On the shuttle, the entire mission is only a week or two. The crew typically has almost every second of their flight booked in the schedule. On a longer flight there might be a few hours of free time, and the schedule sometimes changes, but it’s usually a frantic race to accomplish the mission objectives. On a long duration flight the pace is a little different. And while we’ve seen that an excess can be unwelcome, crews are generally happy to find that they actually have some free time in space. On the weekends, the EO-18 crew would gather around their dinner table to watch movies on VHS tapes, typically dubbed into Russian. This also seems to be the sort of occasion where the smuggled supply of cognac would start to diminish. Thagard said said that he never actually saw anyone drinking it, but on a Friday night Strekalov would float to the base block dinner table and with a smile say, in English, “It’s time to have a drink”

On June 29th, the daily rhythm of the mission was disrupted when a big white spaceplane appeared outside the station. Space Shuttle Atlantis had arrived. Thagard became the first American to watch the orbiter approach from a distance before lining up with the docking port on the Kristall module and moving in to make contact. With the arrival of Atlantis and the STS-71 crew, there were suddenly 10 people on board and a whole lot of work to do. The EO-18 crew did the typical hand-off to the EO-19 crew, explaining where things were and what was going on. They underwent medical studies, and Thagard raided the shuttle pantry, looking for a little variety in his diet.

And speaking of variety in diets, this next part kind of blew me away, but it’s right there in the oral history so I’m just going to go with it. Perhaps celebrating the birthday of STS-71 pilot Charles Precourt on June 29th or Norm Thagard’s birthday on July 3rd, Precourt, Thagard, Strekalov, and Dezhurov made their way over to the Spacelab module in Atlantis’ payload bay. On the way, Thagard found STS-71 commander Hoot Gibson and said “Hoot, I just want to tell you that–” and Hoot cut him off saying “I don’t want to know about it.” So that’s how it was that the group drifted into Spacelab, with the American and Russian flags on the wall, and between the four of them polished off a fifth of cognac. One person would gently stick a straw into their “juice” bottle, take a sip, and float it on over to the next person. So if you’ve ever wondered if anyone’s ever drank alcohol in space, there your definitive answer. To be honest, I’m a little surprised to see Precourt in this group. I’m sure he knew what he was doing, and Thagard said it wasn’t like anyone actually got drunk, but he’s still the shuttle pilot. Theoretically they could have an emergency deorbit at any time and he would’ve been in the hot seat. But I suppose I could also just enjoy this absurd moment as told by an astronaut who clearly had no more fu–ruit juice to give.

We already discussed the other details of what happened when Atlantis was docked at Mir, so we’ll skip to after the successful landing. Thagard did indeed stand up under his own power, despite his 115 days of weightlessness. Though he did admit that it helped that he wasn’t wearing the 90 pound backpack containing his parachute and survival gear. While he still had some balance issues, within a couple of hours the intense feeling of heaviness went away. After getting back to the crew quarters at Kennedy he found a sign in the shower warning returning crew members to not use hot water and not to stand. Thagard promptly took a hot shower while standing with no issues. When the crew returned to Houston, fellow astronaut Bill Readdy met the long duration crew with a van to take them to the crew quarters at Ellington Field, I believe for medical observation. Thagard apparently had other plans, and after dropping off the Russians, asked Readdy to take him home, where he slept in his own bed that night. Within five days he was out doing a three mile jog with the other astronauts. Not bad for four months in space.

This doesn’t really fit in anywhere in the episode, but I do want to mention one last thought from Thagard. He expressed his frustrations with misrepresentation of his mission in the press, which was typically done without even bothering to interview him. He mentions an incident where a Russian newspaper mistranslated something, which was then translated back into English by the American press, and a whole series of articles were based on articles that were based on articles that were based on the original article.. which was wrong. I wanted to call this out because this is precisely how the myth of the Skylab Mutiny got started. So remember folks, do your part to help prevent the spread of misinformation. When in doubt, go to the source!

Alright, let’s say goodbye to Norm Thagard. Or if you haven’t had enough, I really recommend reading his Shuttle-Mir oral history. And if you couldn’t guess by the details he chose to convey in his oral history, Thagard took this as a good opportunity to retire from spaceflight, taking a teaching position at his Alma mater, Florida State University. He mentioned that many of his students didn’t even realize he was a former astronaut. But on the day before the professor evaluation forms went out, he’s spend a lecture showing photos from his space missions. Pretty clever, Norm.

So that’s NASA-1, America’s first long duration flight aboard the Russian space station Mir. The goal had been to learn to work with the Russians, re-learn how to handle long missions, and figure out what NASA didn’t know they didn’t know. There were the expected series of highs and lows, misunderstandings, and camaraderie. And the path ahead was left that much clearer for the six astronauts who would follow in Thagard’s footprints.

I gotta say, in retrospect I’m not sure why I’m surprised by this, but I found this flight to be way more interesting than expected, while also remaining totally doable in a single episode. So I think it’s safe to say that we’ll be taking a look at the other NASA-Mir flights in the months to come. Believe it or not, it turns out that this flight is just a warm-up for some truly crazy moments to come.

Next time.. we turn our attention away from space stations for a while, and wonder why so many people from Ohio are trying to escape the Earth.

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass