Episode 176: NASA-7 - The Last American (Thomas on Mir)

Table of Contents

Andy Thomas’ four month stay on Mir will close out the American presence on the Russian space station. We also wonder what that burning smell is, do a bunch of EVAs, and wave farewell to “Ol’ Stinky”

Episode Audio #

Photos #

Monty Python Game #

Here’s some gameplay footage of that Monty Python video game that Andy Thomas brought to Mir.. for some reason.

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 176, Long Duration Mir flight NASA-7: Последний американец: The Last American

Last time, we welcomed Space Shuttle Endeavour back to operational status, welcomed Dave Wolf back to Earth, and welcomed the view of some relaxing fish, even if it turns out that they may have been dead the whole time. The flight featured a fair amount of science but the primary objective was the transfer of literally tons of logistics and experiments traveling in both directions through Endeavour’s airlock. First and foremost on the transfer list was NASA astronaut Andy Thomas, who became the last American to live and work onboard the Russian space station Mir.

The funny thing was, Andy Thomas was never supposed to fly to Mir in the first place. At least, that had never been the plan. Thomas had been asked to serve as Dave Wolf’s backup and since he was interested in seeing what Russia was all about he agreed, never expecting to actually get a flight out of the deal. But when Wendy Lawrence’s short stature caused her to be pulled from her long duration mission, everybody took a step to the left: Wolf into Lawrence’s mission and Thomas into Wolf’s. Thomas said that the conversation with his family got decidedly quiet when he revealed that he would, in fact, be flying after all.

So nobody had expected it, but I suppose that’s why we have backups, and that’s how it was that Andy Thomas became the astronaut selected to fly NASA-7, closing out the American presence on Mir.

As we saw last episode, Thomas hitched a ride to Mir on Space Shuttle Endeavour, which breezed through a flawless rendezvous and docking. A minor hitch appeared when Thomas struggled to put on his Russian launch and entry suit, which would be necessary in case of an emergency evacuation from the station. But after a little spacesuit surgery (on either his suit or Wolf’s, I’m not actually sure) he was all good to go, joining the Mir EO-24 crew.

Thanks to an oral history interview that Thomas gave around six weeks after returning home, we have a lot of insight into his mental status throughout the mission, or at least his recollection of it. Right off the bat the mission was an adventure, with Thomas finding that when launching from the middeck, the lack of a window means the only option is to imagine what’s going on out there, which turned out to be maybe more dramatic than the actual view from the flight deck. Upon arriving at Mir he went through the traditional shock at the state of the station. He had expected that it was going to be confined and crowded but nothing can truly prepare a crew member for just how confined and crowded the aging space station was. Though Thomas admitted that you do eventually get used to it and he actually never felt claustrophobic during his flight.

One thing I was interested to learn about this flight was how Thomas mentally prepared himself for the lengthy mission. We’ve seen pretty diverse approaches to long duration space flight even among just the six Mir flights we’ve covered. Would Thomas overwork and drive himself into a funk like Blaha? Spend his flight wondering about the next disaster like Linenger? Or maybe bribe his Russian colleagues with Jello like Lucid? Thanks to the work of his predecessors, Thomas had a pretty clear idea of what to expect, and went into it with the idea that he wanted to have a good experience on both a personal and professional level. His thinking was that if he was having a good experience on a personal level, fulfilling his professional duties would be no problem. So with that in mind, the name of the game on this flight seems to be steady attention to detail, but also plenty of attention to his physical and mental health. Which sounds like a pretty good approach to me.

As he watched Endeavour fade into the distance, Thomas was sad to see his friends depart, but glad that life around the station would quiet down a little and he could begin to focus on his mission.

Except, just kidding, because two days later, on January 31st, what’s that outside the window? No, it’s not Endeavour, back for a surprise visit, it’s Soyuz TM-27, carrying the next crew of Mir. After an uneventful approach and docking, the hatch opened and three men piled out, so I suppose we should introduce them.

Commanding Mir Expedition 25 was Talgat Musabayev. Talgat Musabayev was born on January 7th, 1951, in the village of Kargaly, in the Dzhambul Oblast of what is now Kazakhstan. He attended the Red Banner Aviation School in Riga, though I think back then it was called the Lenin Komsomol Riga Institute of civil aviation. Whatever it was called, he graduated with a specialty in aviation electronics. For the next sixteen years he worked in various roles as an engineer and commander for Kazakh’s civil aviation department, including as an aerobatic pilot. He was selected as a cosmonaut in 1990, spending four months on Mir in 1994. This is his second of three flights.

Joining Musabayev on the ride uphill was EO-25’s flight engineer: Nikolai Budarin. We actually briefly met Budarin earlier, when he joined Anatoly Solovyev in catching a ride to Mir on STS-71. Now that he’ll be with us for several months, let’s meet him properly. Nikolai Mikhailovich Budarin was born on April 29th, 1953, in the village of Kirya, in the Alatyrsky district of Russia. He graduated from the Moscow Aviation Institute with a diploma in mechanical engineering, which he put to work at RSC Energia, where he was had already begun employment. In 1989 he was selected as a cosmonaut and as mentioned earlier, he served on EO-19 with our buddy Solovyev, spending a few months on Mir in 1995. This is his second of three flights.

Musabayev and Budarin were also joined by a short term crew member, French astronaut Leo Eyharts. Just like Reinhold Ewald a few missions back, Eyharts would be flying up with the new crew, sticking around for the few weeks of the handover, and landing with the old crew. As such, I’m not going to get into Eyharts’ background, but we’ll see him again a little down the road for a lengthy stay on the ISS.

Thomas’ recollection of this period sounds similar to when the shuttle was still there. It was fun having so many people around, but the station felt crowded and it was difficult to get into a groove with his work. His groove was further disrupted when yet another computer error lead to yet another loss of attitude control on the station. Though compared to earlier incidents this wasn’t nearly as bad. The station’s solar panels drifted off of the sun, reducing the electricity to onboard systems, but the gyrodines didn’t actually stop spinning. If I’ve got it right, they were unpowered but just kept spinning from inertia. The result was that the crew were able to fix the problem pretty quickly by powering down some unessential systems and prioritizing the gyrodines. Never a dull moment on Mir.

Three weeks after the new crew arrived, it was time to say goodbye to the old crew. On February 19th, Anatoly Solovyev, Pavel Vinogradov, and Leo Eyharts all said their goodbyes, climbed into the old Soyuz, and departed for the steppes of Kazakhstan. The reentry went fine but I’m sort of puzzled why they didn’t delay for a day or two, since they actually landed in the middle of a blizzard, complicating recovery efforts. But I guess that’s how Russia does things. For Solovyev and Vinogradov the landing wrapped up nearly 200 days in space.

The next day, it was time for the usual reshuffle of Soyuz docking locations. The Mir program preferred to keep long duration Soyuz spacecraft docked to the node, at the front of the station complex, while leaving the Kvant-1 port at the back available for various Progress resupply ships and eventually the next Soyuz. The three man crew stuffed themselves into the Soyuz, undocked, and backed away from Kvant-1. But instead of puttering around to the other side of the station for a redocking, they just watched as the ground commanded the entire station to rotate 180 degrees around the Kristall/Priroda axis. Once the slew was complete, the crew were now facing the node’s docking port, despite not having gone anywhere, and were able to move back in for a simple redock. I’m not entirely sure what the reason for rotating the entire station was, especially considering just how much stress the attitude control system had been under lately, but it seems to have gone nice and smoothly. If I had to guess, I’d say that this strategy was preferred because the station could slew using electrically-powered gyrodines, while the Soyuz would have had to burn propellant in order to move itself from port to port.

And speaking of docking, just a few days later, Progress M-37 returned from a lengthy free-flight. Several weeks ago it had been told to take a hike, freeing up the Kvant-1 port for the new crew to dock their Soyuz. But rather than reenter right away, it was just sort of parked in a nearby orbit. Ground controllers decided to bring it back, I think so the crew could stuff some more garbage in there. After a thankfully uneventful automated rendezvous and docking, the crew opened up the cargo vessel. Unfortunately, during the three and a half weeks it was flying on its own, a garbage container inside apparently ruptured, and a foul odor flooded the station. Yuck.

Now that the long term crew of Musabayev, Budarin, and Thomas were in place, Thomas was able to finally settle in to his day to day routine. Except, just kidding again. On February 26th, three days after the return of the stinky Progress spacecraft, something happened that resulted in me writing in my notes “Are you kidding me.” There was.. another fire. No, I’m not kidding you. Andy Thomas had just wrapped up exercising on a treadmill in the Kristall module when he drifted into the node, passing the entrance to the Base Block. He was startled to see thick acrid smoke emanating from the Kvant-1 module, just like Jerry Linenger had seen nearly a year earlier. Thankfully, this was not being caused by the oxygen generating “candle” system, but rather the system dedicated to removing contaminants from the air, which is actually pretty ironic.

The device had been misconfigured and instead of venting into space, it was still exposed to the in-cabin atmosphere, overheated, and caught fire. Luckily for the crew, the fire was contained to the unit itself, and was apparently allowed to just burn itself out, which is sort of a bizarre choice but it seems to have worked.

So the fire itself wasn’t actually all that bad, but it came with some alarming new information. First, the station’s fire detection system had apparently been perfectly content to let this one slide, not sounding the alarm at all. Since this happened during the day and the crew were quickly able to shut the machine down this problem didn’t end up being all that bad, but what if a more serious problem had been developing during a crew sleep period? A missed alarm could be far more serious.

Second, the crew were asked to measure the air quality inside the station after the fire was extinguished. When they conveyed their results to the ground they were told that their instruments must have been having trouble because the levels of carbon monoxide they were detecting were far too high to be accurate. I mean, the next day Andy Thomas was feeling lousy enough to don an oxygen mask, but surely it must be instrumentation, right? Nope! The crew collected samples of the air that was measured later, and it was discovered that the carbon monoxide levels had been something like 20 times higher than safe limits and remained high for days. So I guess the instruments were right after all. Whoops!

I’m starting to think that between the first fire, the stinky Progress, and the second fire, maybe it would be best if the hatch between the Base Block and Kvant-1 was kept closed most of the time.

OK, but for real this time, with the shuttle crew gone, the Mir 24 crew gone, and the carbon monoxide gone, Andy Thomas was finally able to properly settle into his groove. Based on Thomas’ recounting in his oral history, his stint sounds considerably more relaxed than some of the earlier ones. The crew would typically begin work around 9am and continue until 7pm, but with a break in the middle for exercise and lunch, when they’d usually eat together so they could chat. And of course, they’d gather in the Base Block for communication passes with the ground.

Thomas’ main work was mostly done in Priroda and focused on the 27 different experiments carried up on the shuttle. As always, these touched on a variety of different subjects including earth sciences, human life sciences, microgravity research, and ISS risk mitigation. In good news for the science but sort of bad news for an interesting story, the science seems to have hit no major hitches. The biggest problem seems to have been the formation of bubbles in the Biotechnology System Co-Culture Experiment. But this was actually nothing new, it was giving John Blaha trouble all the way back on NASA-3. I’m betting that the most unpleasant experiment was one where Thomas had to collect his urine so scientist could study if all the bone loss from weightlessness put astronauts at risk of developing kidney stones. Delightful.

I thought it was interesting that in his own blog-like letters home, Thomas also experienced the same issue as Wolf in that he just kept losing stuff. As fun as zero gravity is, it’s not the most conducive to getting stuff done. He said that he would turn his head for a moment and then something he had left floating would be gone. Sometimes it had actually drifted off, but sometimes, like Wolf, he just couldn’t see it. His brain would instinctively scan any surfaces that appeared horizontal to him at the moment before he would remember that there was no reason for the missing object to be in those places. But with a little effort, he eventually had a nice collection of tethers, velcro, and spare pens and pencils set up in his workstation in Priroda.

While a smooth mission is what every astronaut hopes for, Thomas did admit that the flight could get a little monotonous. Because of that, he emphasized the importance of recreation. He said quote “recreation is very important, because that’s how you regenerate yourself and keep charged up to get the work done and to fulfill the requirements of the mission under these very trying circumstances,” later adding “because you can’t physically escape the environment, but psychologically you can.”

Because of that, Thomas arrived with a solid amount of entertainment to help recharge during his off time. There was the usual fare such as cassette tapes and CDs with a variety of music, along with a decently large collection of VHS tapes with movies and recorded sports games on them. And of course, Thomas enjoyed frequent correspondence with friends and family on the ground both over the radio and via email. He said he actually preferred email because voice communications were so fleeting, while an email could be re-read and he could take his time crafting a response.

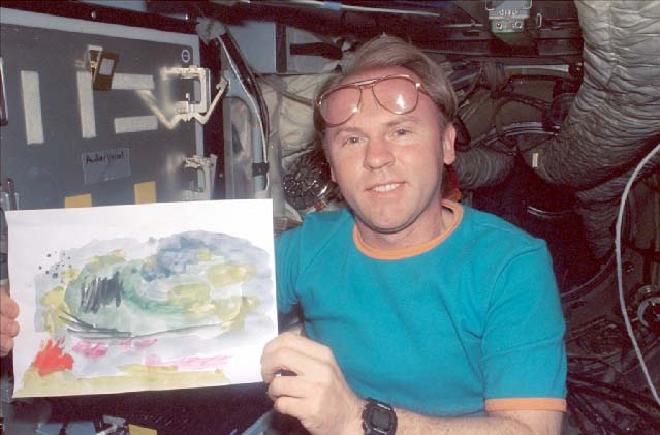

Not all relaxation time was electronic in nature, though. Thomas tried his hand at a guitar that was onboard the station, only to discover that playing a guitar in weightlessness is actually somewhat challenging because the instrument no longer rests in your lap as you play. He also drew some sketches of scenes around the station and out the windows. He said that while he was proud of the sketches, they weren’t all that remarkable. But one reason he enjoyed them was that he found them so engrossing that suddenly he’d realize he had been completely absorbed in one for hours. And of course, as Shannon Lucid would point out, for non-electronic entertainment you can’t go wrong with a good book. Among the ones that Thomas read while whizzing around the Earth was Huckleberry Finn, which he had always wanted to get around to reading.

But the recreational activity that caught my eye was a certain CD-ROM. As someone who has played video games pretty much his entire life, I was extremely interested to learn that Andy Thomas had flown to Mir with a PC video game among his entertainment options. Of course, in early 1998 there was already so much to choose from. Would he go with one of my favorite games, X-COM: UFO Defense? It seems like it’d be on brand. Or maybe something a little more realtime, with a game like Doom or Quake. What better way to take out the frustrations of unwanted bubbles in a biotechnology experiment than to shoot a Cyberdemon? Or maybe even some good old fashioned adventure games like The Secret of Monkey Island, something a little more tolerant of using a laptop nub to control the mouse. The answer was.. none of these! Thomas chose “Monty Python’s Complete Waste of Time”. This collection of mini-games and full motion video lives up to its name. It comes from that multimedia CD-ROM era where you didn’t really have to be much to call yourself a game. And, well, of all the video games that exist in the world, it certainly.. is one. I’ll include a link to a gameplay video in the show notes and on the show’s twitter page so you can judge for yourself.

But the reason I’m giving this terrible game so much attention is that as far as I can tell, this is only the second video game ever flown to space, and the first by an astronaut. You’ve got about five seconds to guess the first game in space. I’ll give you a hint (hums Tetris theme) that’s right, it’s Tetris. Specifically, Tetris for the Game Boy, which according to the Guinness Book of World Records was flown to Mir by cosmonaut Aleksandr Serebrov in 1993.

And of course, when not reading about Huckleberry Finn or puttering around in the Monty Python game, there was always food to enjoy. Thomas had high praise for both the American and Russian food, in particular saying “The soups are outstanding and the juices are just marvelous, and there’s plenty of it.”

On March 4th, Thomas prepared to have the entire station to himself as Musabayev and Budarin suited up for a trip outside. Unfortunately, they didn’t quite get there. As part of the updated egress procedure with the problematic hatch, the crew were required to use a wrench to turn ten latches. Nine of them opened for the crew, but the tenth remained stubbornly closed. It remained so closed that Musabayev broke not one, not two, but three wrenches trying to open it. I’m not sure I should be impressed by Musabayev’s strength or unimpressed by the quality of the wrenches, but either way, the heads of the wrenches just snapped off. Ground control told him to stop, presumably before he broke every wrench on the station. They would just have to wait until Progress M-38 arrived with some specialized tools.

This was actually kind of a big deal. Obviously it was a problem since it held up the goal of the EVA, which we’ll get to in a little bit, but it also means that no EVAs were possible at all, even if it was an emergency. With all the ports of the node occupied, Kvant-2 had the only airlock on the station. I guess they could have sent Progress M-37 away and moved the Soyuz from the node port back to the Kvant-1 port but that’s not something you want standing between you and your emergency EVA. So I guess we’ll just wait and hope.

A couple weeks later, Progress M-38 launched successfully, and M-37, aka Ol’ Stinky, was sent off to a fiery demise. Two days later, Progress M-38 docked after a mostly nominal approach. Commander Musabayev saw something he didn’t like in the final approach and took over manual control with the TORU, but since it was only around 20 meters away from the station, docking under manual control was no problem.

Progress M-38 was actually pretty interesting because it carried some external cargo that we’ll get to in just a few moments. I was curious what this actually looked like, so I went to an image search engine and put in “Progress M-38 photo” and instead of the spacecraft, I got a bunch of weight loss progress photos of males aged thirty-eight. Oops.

To the crew, Progress M-38 meant the arrival of the tools that would enable the upcoming set of EVAs, as well as some welcome treats from the ground. Instead of stinky garbage, the aroma of fresh apples greeted the crew, along with some digital photos, a CD player, and some Beatles albums.

And we’ll get to those EVAs in just a second, but in between the Progress docking and the first spacewalk was a notable milestone. On March 22nd 1996, STS-76 had launched carrying NASA-2 astronaut Shannon Lucid. Well, it was now March 22nd 1998, and in all that time, at least one American had always been in space. Two years of continuous presence in space is a pretty notable achievement, so congrats to all those who worked to make that happen.

Alright, but now that we have the proper tools, it’s time to get to work on these EVAs. We’ve actually got a grueling batch of five EVAs, in a pretty short amount of time. For a lot of these spacewalks I’ve found some fun little details courtesy of Chris van den Berg, who was again listening in to the communications thanks to Russia’s use of the Altair-2 geosynchronous communications satellite. It’s a shame I only found van den Berg’s Mir News updates for these last two stints because there’s all sorts of interesting details and commentary in there. Oh well, better late than never.

On April 3rd, Musabayev and Budarin succeeded in getting the hatch open, and crawled out onto Mir’s exterior. The main goal of this spacewalk was basically to do some prep work for other spacewalks to follow. There was a desire to add some bracing to Spektr’s damaged solar array, strengthening it. But first, they had to prepare the work site, setting up handrails, foot restraints, and so on. The six and a half hour spacewalk hit no major issues except one. Part way through the EVA commander Musabayev suddenly stopped responding. Some period of time later, I’ve seen “several seconds” and “a few minutes” both listed, he began responding again. It turns out he had accidentally turned off the power supply to the suit, losing comms, cooling, CO2 scrubbing, ventilation, everything. He managed to get the suit powered back up again but it was a pretty scary moment.

A few days later, they were back at it again, heading outside to finish installing the support brace for Spektr’s solar array and take care of a few other things. They were able to finish bracing the solar array but the task took longer than expected, leaving less time for the next items on the list. But it turns out it didn’t matter anyway because ground controllers suddenly asked them to quickly wrap up the spacewalk and get back inside. The reason for ending the spacewalk early was actually related to their next task. Outside of Kvant-1 was a fourteen-and-a-half meter long girder, topped with the VDU attitude thruster. VDU stands for something in Russian but don’t make me read it. Those who paid attention in physics class will know that the benefit of putting a thruster out on the end of a long girder was that it increased leverage and allowed the thruster to exert more torque on the station while using less force, saving fuel. The remaining EVAs were actually dedicated to replacing the aging VDU, the new one was that exterior cargo I mentioned on Progress M-38. But in the middle of the EVA the ground reported that the VDU had run out of fuel, right this moment, causing the station’s attitude to drift. The Russian crew hustled back inside to fix the situation.

But here’s something sort of odd. While this is apparently still the official story, and repeated in several sources, there’s some doubt that it’s actually what happened. One source hints at this by reporting that the EVA was ended early due to what was misdiagnosed as VDU fuel depletion. But a familiar name provides more details. James Oberg, a Russian spaceflight expert who we saw testify at the Mir safety hearings before Congress, says that in reality, the ground sent an incorrect command up to the station. Then, not realizing their error, they mistakenly attributed the drifting attitude to a lack of VDU fuel. As always with the Russian side of things, I’m not entirely sure what the truth is here, so I’ll leave it up to you to judge. In any case, the truncated spacewalk lasted four hours and 23 minutes.

Five days later, it was time to suit up for a third time. As Thomas once more watched from inside, Musabayev and Budarin crawled out onto Kvant-2’s exterior and made their way over to Kvant-1 to get to work. On this spacewalk they basically wrapped up the previous spacewalk, collecting an experiment, jettisoning some unneeded equipment, and disconnecting the old VDU. Though I’m sort of confused why it was OK to take down the old VDU if its contribution to attitude control was so important that the last EVA had to be cut short. Like.. what was the plan? “Hey, don’t throw away the VDU, the VDU stopped working!” Chris van den Berg noted something that made me laugh but also sort of confused me. Apparently Commander Musabayev wanted Thomas to observe and take photos as the old VDU was jettisoned. Thomas did so, but due to the angle of departure and the limited windows, was only able to watch it for a few minutes. According to van den Berg, quote “Musabayev did not like this and did not hide that verbally. Let us hope that Andy

neither heard nor understood this.” What? Was Musabayev upset that Thomas couldn’t see through walls? Anyway, six hours and 25 minutes later, they were back inside.

Six days later on April 17th, they were back outside, doing some final prep work with the new 700 kilogram VDU. This involved setting its girder at a specific angle and bolting it into place to make the final VDU replacement easier, along with dismantling and storing some other trusses for future use. After another six and a half hours outside, the spacewalk came to a close.

Finally, on April 22nd, the duo headed outside one last time, attaching the new VDU to the end of the girder and moving the girder back up into its vertical position. Or I guess horizontal position, depending on how you want to think about it. With the new, fully fueled, VDU in place at the end of the girder, Mir regained enhanced attitude control about its long axis.

Not counting the several hours of troubleshooting on the first failed EVA attempt, the five-spacewalk series added up to just over 30 hours outside the spacecraft. Andy Thomas later said that he would have liked to tried a spacewalk of his own, and he would later, but also that thirty hours of spacewalking is hard hard work, which he did not envy.

One sort of funny side note on the EVAs.. according to Chris van den Berg, the Russians happened to use a similar radio frequency as a nearby airport. This was a nuisance for van den Berg since sometimes the airport traffic clashed with the space-based traffic he was trying to listen to. But it was also occasionally a nuisance for the Russians, who apparently would sometimes get snatches of conversation from ground crews at the airport. And during one of these EVAs, van den Berg reported that for the first time, someone on an airport ground crew realized this, and radioed up “dosvidanya.” I can only imagine the reaction of the Russian crew.

As I mentioned earlier, this was a pretty trouble-free few months on Mir, even if we did have that one minor attitude computer problem and of course, the second fire. But really, all the hard work of the previous crews must have been paying off because for the most part it was smooth sailing. So it was pretty funny when right near the end of the flight, just as Andy Thomas was about to do a video interview with the press about his trouble-free flight, the attitude control computer again had a problem and the station slewed off the sun. In what Thomas called “unbelievably bad timing” they had to cancel the interview about their problem-free flight.. in order to solve a serious problem.

And actually the stakes were a little higher than just a missed press interview. Space Shuttle Discovery was on the pad and planning to launch in just a few days to retrieve Thomas. If Mir’s attitude was drifting, rendezvous would not be possible. Thankfully, after a day and a half or so, control of the station was reestablished and everything was back to normal.

That launch was delayed by five days due to ground crews needing a little more time to prepare the shuttle, but given the timing of the attitude problem, it may have been lucky after all. We’ll cover the details of STS-91 in a couple of episodes, but for now we’ll say that it arrived at the station on June 4th, with a bunch of new supplies and equipment, but no replacement astronaut. A few days later, Thomas said his goodbyes to his Russian colleagues, took one last look around the station, and moved over to the Shuttle. Once the hatches were sealed and Discovery departed, no American would ever again float foot on the Russian space station.

Thomas later described the departure, which I’ll just read in a bit of an extended quote. “Perhaps one of the most moving moments, though, was as we drew further and further away. We went into the night side of the planet, and I could see the stars, and the running lights of the station were on. You couldn’t see the station. All you could see was lights flashing, and they were just going off into the distance, these flashing points of light fading out slowly. That was kind of an emotional moment, because I knew that would be the last time I would see it - ever.”

After returning to Earth from his nearly 132 days in space, Thomas said that while none of his family members had expressed any concerns about his safety when he announced he would, in fact, be going to Mir, there sure was a lot of relief expressed when he came home safe and sound. With his year and a half Russian adventure over, Thomas turned his attention to living without a schedule for once, and turning his new house into a home. Don’t worry though, we’ll see more of Andy down the road.

And that was it for the Shuttle-Mir program! I’ll have some more things to say in upcoming episodes since we still have to cover the flight of STS-91, the last Shuttle mission to Mir, and I’ll do a little retrospective on the entire program, but we’re all done with long duration crews for now. But before we get to STS-91 and a Goodbye-Mir episode..

Next time.. we once again hop back in time a little bit to see what the space shuttle was up to while Andy Thomas was flying around in Mir. With STS-90, Space Shuttle Columbia is back on the launchpad with our old pal Spacelab in the payload bay for one last flight. So it’s time to drift down the tunnel and get nervous. Er–, I mean, get to know the nervous system.

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass.