Episode 173: NASA-6 Part 2 - Stuck Between a Hatch and a Cold Place (Wolf on Mir)

Table of Contents

As Dave Wolf wraps up his stint on Mir we try to be efficient with our comms, try not to spill too much caffeine, and try not to get locked outside the station!

Episode Audio #

Photos #

Video tour #

Here’s a short video where Wolf shows us around Mir.

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 173, Long Duration Mir Flight NASA-6 Part Two: Stuck between a hatch and a cold place

Last time, we rode along with astronaut Dave Wolf as he became the sixth American to serve on a long duration flight on the Russian space station Mir. Compared to his predecessors his flight so far has been going extremely smoothly, but in space there’s always some new complication to look out for. Today, we’ll look at the second half of Wolf’s flight, focusing in particular on some fun aspects of day to day life, an EVA that almost didn’t happen and ended up being more excitement than Wolf bargained for, and a peek into how the Mir astronauts interacted with their American support teams.

When we left Wolf, he had settled into a good routine, getting lots of science done while also doing his part to help maintain the aging space station. He had come a long way from the early part of the mission where he was still finding his space legs. In his blog-like “letters home”, Wolf documents the process of learning how to live on Mir. For him, it took about two months before he began thinking and moving as a true resident of space, internalizing the lessons learned over the course of the flight.

Just as an example, Wolf describes how three weeks into the mission he looked up at a gas analyzer on the ceiling and was momentarily flummoxed on how to get quote-unquote “up there” to read it before remembering that, oh right, he can fly now. On another occasion he was traversing a module and came across his crewmate Pavel Vinogradov. He politely waited a few moments for the Russian to clear a path before he remembered that he could just move up and drift over his head. Yet another important lesson came from habitually picking up too many items at once when working, only to realize that there’s no way to put them down!

Another effect of living in space that took months to resolve seemed to be related to some sort of filter inherent to human vision. Wolf describes the bizarre experience of using a wrench, then positioning it in front of his face and letting it go as he continues his work. Moments later he looks back up to get the wrench and.. it’s gone! It could be that it had migrated to the air filters, as anything that’s not tied down will eventually do if it’s able to navigate the station’s clutter. But actually, no, it’s still right in front of his face, but since no matter how careful he was Wolf would inevitably impart a small rotation to any item he let go of, it had changed its attitude. Wolf, looking for the wrench, found that he literally couldn’t see the same wrench now that it was pointed away from him or in some other orientation. His hypothesis was that his brain was looking for a specific item as he remembered it looking and essentially filtered out any unrelated items since they weren’t relevant to the search. Ironically, Wolf found that the way to find the missing tool was to actually stop looking. Once the search was off, his filters apparently relaxed and he would suddenly notice this unexpected object floating in front of him, bumping him on the forehead.. and oh hey! It’s that wrench!

Yet even with his brain and body fully accustomed to space, it’s hard to shake decades of Earth-bound intuition. Wolf describes waking up one morning from a dream where he and a bunch of friends were playing volleyball in weightlessness.. except for some reason they could never quite make it all the way to the ceiling. Even in the dream world, the brain apparently resisted the concept of free movement in all three dimensions.

Yes, things were going well for Wolf, but no trip to Mir is going to be completely smooth. On November 13th, a week after Solovyev and Vinogradov spent two EVAs installing a new solar array on Kvant-1, the crew were testing the new array. Unfortunately, the test didn’t go great, with the station momentarily losing power, once again throwing the attitude control system out of whack. The crew moved some fully charged batteries from Kristall to the Base Block, which restored power to enough gyrodines to begin to stabilize the station, but not quite get the job done. So for the next 48 hours or so the men would sleep in shifts, with someone always awake and keeping an eye on the systems. Whenever Mir happened to enter an attitude that was favorable for power generation, they’d flip the appropriate switches and begin charging the batteries back up again.

Just a week later, another malfunction again knocked Mir out of its nominal attitude. This time the fault actually came from the computer which STS-86 commander Jim Wetherbee was so happy to deliver to the station. The crew were able to swap the computer with a similar one that had arrived on a Progress resupply vehicle after the shuttle departed, but again had to endure a roughly 48 hour period of attitude recovery.

Wolf talked about how eerie it was to be on the station with none of usual background noise provided by fans, pumps, and other equipment. Space was suddenly dark and quiet, an unusual experience for any space traveler.

On December 17th, the crew gathered to watch the departure of Progress M-36, which promised to be especially interesting thanks to the inclusion of a nifty little German payload named Inspektor, but spelled with a K instead of a C. Inspektor was a mini satellite that was deployed from Progress as part of a tech demo. The 72 kilogram satellite contained a video camera, star tracker for attitude control, and some small thrusters. The plan was for it to separate from Progress M-36, orient itself, and then begin slowly circling the resupply vehicle. After that, Vinogradov would take over manual control and fly back to Mir, where it would circle the station. The hope was that such a spacecraft could be used for inspecting (oh hey, I get it) the exterior of Mir or the ISS without the need for an EVA. It was a pretty cool idea that probably would’ve resulted in some really spiffy video footage, but unfortunately it was a bust. Shortly after separating, its star tracker instrument overheated and failed, leaving the tiny satellite with thrusters that could control its attitude.. but no idea what its attitude was. The disheartened crew could only look through the window and see the hapless spacecraft spinning out of control before drifting away. It was especially a bummer for Vinogradov who was looking forward to piloting Inspektor, but these things happen.

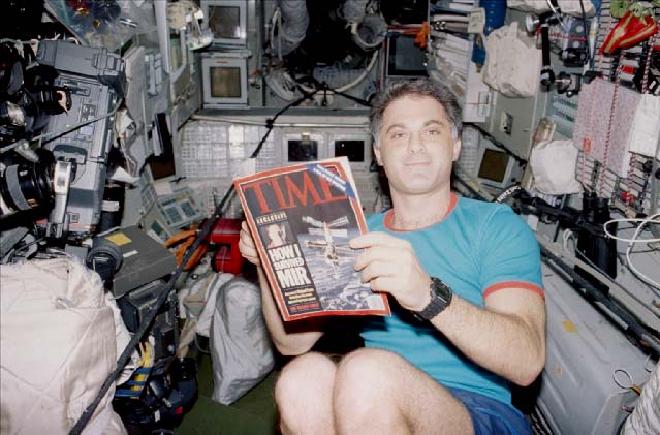

But maybe it was even worse for Wolf and Solovyev. Just before the Inspektor demonstration was going to begin, Wolf had prepared a bag filled with hot coffee, sugar, and cream. Realizing that it was actually a little over-filled, when Wolf needed the use of his hands he simply held the bag in his mouth, clamping it shut with his teeth. Hoping to get a better look at the demonstration spacecraft, Wolf moved over to a window that happened to be in Commander Solovyev’s sleeping quarters. So of course, right as he gets in there, his headset wire gets snagged and yanks his head back, dislodging the coffee bag. The bag then starts dumping hot coffee quote-unquote “at a surprising race” all over Wolf’s face, up his nose, and into his eyes. But since this is space, it just sort of stayed there, glomming on and adhering to his face. Thinking quick, and not wanting to soak Solovyev’s belongings, but unable to communicate what was going on, Wolf frantically moved back out of the compartment as a gurgling mess. He soon freed himself, regaining the ability to breathe, and began cleaning up the coffee while Vinogradov laughed hysterically. The worst part was that this was well after the two month point where Wolf himself declared that he was fully acclimatized to space, so he didn’t even have an excuse! In a letter home discussing the event, he explained to his operations lead quote “that’s what all the gurgling was on the air-to-ground loop earlier.” No word on how much coffee got on Solovyev’s stuff.

As the end of Wolf’s mission rapidly approached there was major task remaining that he was very much looking forward to: his first EVA. The fact that the spacewalk was on the table at all for Wolf was a testament to all the hard work that he and his Russian trainers put in during the crunch period after learning that he would fly to Mir several months earlier than expected. But all that work was to just maintain the option of doing a spacewalk, it wasn’t a sure thing. One part of this was that there was a lot of science to be done on this flight, and all of it required Wolf’s attention. And since some of it also required examination of his own body, the EVA and preparations for it would interfere with the ongoing science. Thanks to his support team on the ground and his seemingly untiring efforts day after day, the science folks were eventually satisfied, and with Russia’s sign off, Wolf was ready to head outside.

For Wolf this was a really big deal. When he was a kid he had seen footage of Ed White performing NASA’s first ever spacewalk and that was what had inspired him to become an astronaut in the first place. If you’re wondering, before that moment his career goal was to become a garbage man.

On January 14th, 1998, Dave Wolf joined Mir commander Anatoly Solovyev in the Kvant-2 module and they began to suit up for the journey outside. This may have been Wolf’s first EVA, but it was Solovyev’s 16th, a record which as of 2023 stands to this day. So while for Wolf is was the fulfillment of a life-long goal, to Solovyev it was Tuesday. Well, it was Wednesday, but you know what I mean.

Before we get into the EVA, I need to talk a little about the research I put into this EVA. Of course, this podcast is really about spaceflight history, but every once in a while it’s fun to talk just a bit about how it gets made. If you are listening to this episode in realtime you will no doubt have noticed that the episode slipped by a week. A big part of that was that my plan for writing this episode was something like “OK, I’ll talk some more about day to day life on the station, the power and attitude problems, that funny little Inspektor payload, and then the EVA should take up the rest of the episode.” I had read some brief summaries of the EVA and also knew that I had heard some interesting details about it on an episode of Radiolab in the past, so I figured it’d just be a matter of gathering up the last few details and weaving it into the show. It turns out I found a bit of a rabbit hole.

The WNYC show Radiolab interviewed Dave Wolf in 2012, where he gave sort of off the cuff answers about his spacewalk on Mir. The details were largely what I had remembered from when I heard the show years ago, and with the knowledge I’ve gained about Mir, I could better piece together what exactly was going on. But there were some odd details. For example, hosts talked about Wolf having done dozens of spacewalks, while the actual number is 7. OK fine, but these guys aren’t space experts, so whatever. But then Wolf talked about spending something like 10 hours troubleshooting a problem at the end of the EVA. But.. nothing else I saw said that this happened. So I went hunting for more details.

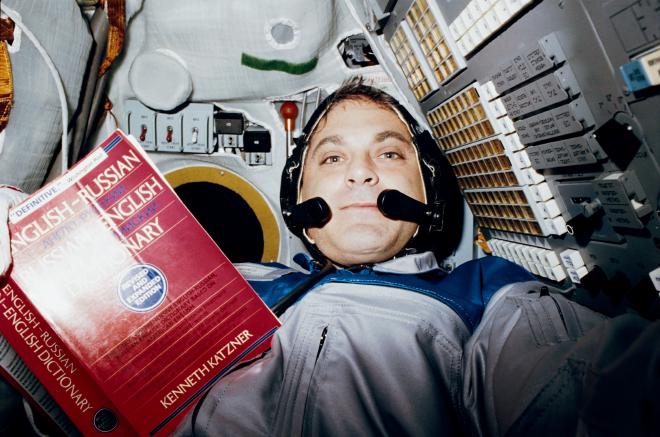

While digging through archived websites from the 1990s, I saw someone mention seeing some piece of data in a series of Mir news bulletins, but with no link to the bulletins themselves. These were apparently a series of hundreds of updates in a sort of proto-blog posted on usenet groups by a dedicated space nerd named Chris van den Berg. Chris van den Berg was a pretty interesting dude. I found another source that shares recordings he made of radio broadcasts of early Soviet crewed missions, going all the way back to 1963. This is the moment that I made a connection to a funny line in an oral history with Dave Wolf’s flight surgeon Chris Flynn. Flynn had mentioned that how even though they called it a private medical conference, there was quote “a guy on a ham radio in the Netherlands who would type out whatever we said.” And that was him! Chris van den Berg was the guy with the ham radio!

After still more digging, I discovered that noted astronomer and spacecraft tracker Jonathan McDowell had an archive of van den Berg’s “Mir News” bulletin going all the way back to the 1980s. He was gracious enough to dig through his archives and post a bunch more bulletins, including the one that covered this EVA, so thanks very much, Jonathan.

So this EVA account comes from the somewhat terse official records, Wolf’s recollections in a 1998 oral history, Wolf’s somewhat suspect recollections from a 2012 interview, and Chris van den Berg’s realtime reporting from 1998. It’s just fun to think that this information started when the crew said it out loud, it was beamed to a Russian satellite in geostationary orbit, which beamed it back down to Earth, was then picked up by van den Berg, who then posted about it on usenet and/or email lists, which was saved by Jonathan McDowell, who held onto it for 25 years, and then was kind enough to post it on his website when I came stumbling into all of this, and now I’m reading it to you. Given all that, I won’t be shocked if not every detail is perfect, but I’ll do the best I can with what I’ve got.

As Solovyev and Wolf headed outside, it was into darkness, as Mir passed behind the Earth. Since the station had no exterior lights, all they had were the small lights on their suits, which meant that it was dark out. Really dark. Wolf described the eerie sight of the Earth as a black void, notable only for the absence of stars. Wolf was happy to discover that he didn’t suffer from unpleasant sensations experienced by other spacewalkers, like the feeling of tumbling end over end. But when the sun rose he suddenly became keenly aware of his altitude and velocity, which caused him to clutch onto the handrails. But with work to do, there was little time to admire, or be intimidated by, the view.

The plan for this spacewalk was for Solovyev to continue to work on the problematic airlock hatch, while Wolf crawled around the exterior of the Kvant-2 module testing out a fancy new instrument called the space portable spectroreflectometer, shortened to SPSR. This was a sizable but still handheld instrument that would examine the light reflected from various surfaces outside of Mir and determine their characteristics. In essence, it was the Long Duration Exposure Facility, but instead of bringing the material back home to study it in a lab, Wolf would use a handheld instrument to measure the material right there outside Mir. The instrument sort of worked, but had issues with its display, and could only be used with Wolf coordinating with Vinogradov, who was supporting them from inside the station. It also proved to be difficult and cumbersome to both handle and read the data, especially with the balky display.

But really.. the goal of this EVA was to have an EVA. As always, NASA had its eye on the upcoming ISS and was hungry for more EVA experience, eager to get its astronauts outside the spacecraft whenever it was reasonable. Doing an EVA with Solovyev was even better, since who better to learn from than the world record holder on EVAs? Listening in to the air to ground transmission, Chris van den Berg’s impression was that Solovyev had a lot of work to do in keeping an eye on Wolf, who was qualified for the spacewalk but had a lot less practice than was typical. Solovyev pointed out a sensor that Wolf had to avoid, advised him to keep his movements smaller to remain under control, and to keep things short when speaking.

To me, this firm handling doesn’t seem unreasonable, nor does it impeach Wolf’s spacewalking abilities. Solovyev was the mission commander, was a mega-expert on this, and was Russian. It was only natural for him to be terse and direct. But Solovyev also had a special treat in store for Wolf. At one point in the spacewalk, as another night pass approached, mission control asked the two men to pause their activity and simply wait for the sun to come back in a few tens of minutes. Solovyev invited Wolf to turn off his helmet light, presumably double check his tethers, and let go of the station, turning to face the night sky. Wolf had also turned the suit’s cooling system down a bit, which made him a bit warmer and the noise a bit quieter. Recalling this moment in 2012 he said quote “I felt like I didn’t have a space suit on. It was so comfortable, the air temperature was just right. I felt like I was just out in the universe, in the stars – I couldn’t see anything but stars all around me and I couldn’t feel anything.. outside a spacecraft going 5 miles per second, out in the universe.” We’ve talked about some pretty magical moments up in orbit, but Dave Wolf staring into the universe is up there for me.

After a few short hours it was time to head back inside. Wolf and Solovyev clamored back into the Kvant-2 airlock, closed the hatch, and.. oh. The hatch won’t close. That’s.. not ideal. It sort of closed, and even lit up the indicator that said it was closed, but air pressure was not building up properly and there wasn’t nearly enough air for the spacewalkers to take their suits off. There was, however, enough air to start interfering with the suits’ cooling systems. This was.. very bad!

Let’s leave Solovyev and Wolf hanging for a minute and take a step back to figure out just what’s wrong with this darn airlock that’s been giving us so much trouble in the first place. Way back in November of 1989, Mir was just a little baby space station. The only components in place were the Base Block, Kvant-1, and depending on when you checked, maybe a couple of Soyuz or a Progress vehicles. But launching atop a Proton rocket, the Kvant-2 module soon found its way approaching the nascent space station.. before departing again due to some rendezvous issues. A few days later though, it closed the gap, docking with the node at the front end of the base block. For whatever reason, Kvant-2 didn’t get its own fancy name like later modules, which is how we ended up with both Kvant-1 and Kvant-2, with “Kvant” translating to “Quantum”.

Kvant-2 arriving was a big deal. It carried new gyrodines that would help with attitude control, new water and oxygen recovery systems, and even a shower. Yes, the Russians apparently hadn’t learned that particular Skylab lesson because they thought a shower would be pretty cool. Of course, they soon figured out why the shower was so rarely used on Skylab: the water stuck to the cosmonauts’ bodies and to the walls, making it a big hassle to clean up afterwards. The shower would eventually be converted into some sort of steam shower, because what Mir definitely needed was more humidity, before it was finally sacrificed in the name of additional storage space. But that’s besides the point, the shower was not the reason Kvant-2 was a big deal: its airlock was.

Before the new module’s arrival, spacewalks were performed by opening one of the unoccupied hatches in the node. This worked but wasn’t ideal. The crew would have to seal off every other hatch, which at this point just would’ve been the Soyuz and the Base Block, but was still a hassle. Also, the node’s hatches were a little smaller than the airlock hatch in Kvant-2. Lastly, in a first for the Russian space program, the Kvant-2 airlock had an outward opening hatch, which made it much easier to get equipment through.

But that outward opening hatch is also the root cause of all of this trouble. At the start of only the fourth spacewalk from the new module, back on July 17th, 1990, the perhaps over-eager crew accidentally turned a wheel a little too far, releasing hooks and opening the hatch a little too early.. before the airlock had a chance to purge the last traces of air. When pressure acts on a large surface it can push with a surprising amount of force, and even with only 5% of sea level pressure still in the airlock, around 400 kilograms of force was being exerted on the hatch, nearly 900 pounds. So of course, the hatch flew open and slammed against its hinge, distorting the mechanism. And just who was the unlucky spacefarer who was in command for this mishap? Ah, says here it was some cosmonaut performing his first ever spacewalk.. Anatoly Solovyev. Oops.

The hatch continued to have trouble sealing until the next crew arrived with the proper tools to effect a repair. And that repair mostly held up over the years, but apparently Vasily Tsibliyev wasn’t wild about it and forbade Jerry Linenger from touching the clamps that were now holding the hatch together. And I guess he was right because here we are again, with Solovyev struggling to get the hatch to seal.

Officially, the spacewalk ended when the hatch closed, adding 3 hours and 52 minutes to the running tally. But while the hatch closed, one of the ten latches wasn’t slotting into place, with the result being that the compartment would not hold pressure. Solovyev spent around an hour and a half troubleshooting the issue, but this couldn’t go on indefinitely. Eventually the carbon dioxide scrubbers in the Orlan suits would be saturated, the crew would begin to get a bad headache, then their vision would go fuzzy, and then they would lose consciousness. Thankfully, while this was a serious situation, it wasn’t quite as dire or hopeless as it might seem.

Kvant-2 was broken up into three internal sections, and each one could be sealed off from the others. So the option existed to simply move out of the airlock and into the middle compartment, sealing the hatch behind them and using the middle compartment as a sort of emergency backup airlock. As Wolf describes it, the only way to do this was to unhook some umbilicals before moving through the inner hatch. The only trouble is that as soon as this is done, the suit visor fogged up, and both men began getting warmer and warmer, with only a few minutes until they would overheat. Groping around the module and navigating by feel, Wolf made his way towards the hatch, aided by spitting onto the visor and gaining a tiny window through the fog. Once inside, they closed the inner hatch, and were able to repressurize and remove their suits.

Wolf later said quote “When I look back at that experience, I shudder. But at the time, the two of us were just trying to resolve the problem step by step and I didn’t even feel nervous.”

And for those who were wondering how those earlier problematic EVAs ended, yes, they used a similar solution. I just left that out to create more drama.

Like I mentioned on the previous episode, the cosmonauts did not give out compliments lightly, so Dave Wolf was pretty pleased with himself when after the ordeal was done, Solovyev turned to him and said “Good job.”

One thing that was fun about researching Wolf’s stay on Mir was that thanks to oral history interviews with his Ops Lead Patti Moore and his Flight Surgeon Chris Flynn, we get a little more of a glimpse into Wolf’s relationship with the ground while orbiting the Earth. While Atlantis was still docked, Wetherbee said that Wolf liked to flip around the typical way that people think about spaceflight and risk and safety by ending his transmissions to mission control with the warning “Now, be careful down there. You’re awfully close to the ground, you don’t want to get hurt.”

Once Atlantis left, access to TDRSS left with it. While the crew were able to use the Russian equivalent during special events like the EVA, they were typically constrained to 10 or so minute long passes while flying over Russian ground stations. And from what I can tell, Wolf would typically only get one of those passes a day to talk with his own support team. Flight Surgeon Chris Flynn talked about the challenges of working with such a small amount of time. Both sides had a lot of information to convey as quickly and efficiently as possible. It helped to have experts readily on hand so time wasn’t wasted going to get the right person. And it was really important to be sure of what you were saying, since a thoughtless mistake might cause Wolf to lose an entire useful day on orbit as he toiled away with the wrong information.

But despite the importance of conveying this information, it was also important to keep Wolf’s mental health in mind. Since the ground crew didn’t want every second that Wolf was interacting with them to be a high pressure work-oriented discussion, they would also discuss lighter things from day to day life, helping keep the astronaut connected to life down on the planet. And one time, they really went all out, dedicating an entire video conference to a fun surprise for Wolf.

The ground team wanted to gift Wolf with a moment to laugh and relax and were careful to think about the best approach. For example, they specifically didn’t make it interactive since they didn’t want to put Wolf on the spot and make him be “on” and basically force him to entertain them. So instead they did a series of skits to make sure that the entertainment was going from the ground to Mir. In one skit the timeline schedulers came on camera dragging six foot long printouts and asking Wolf if he could just add these few items to his todo list and get through them by tomorrow. And in another skit Tom Marshburn and Joel Montalbano strutted into frame wearing tracksuits stuffed full of rags and other clothes to make them look super buff. They then went through a whole routine, imitating the characters Hans and Franz from Saturday Night Live, and telling Wolf how important it was that he do a lot of weight lifting while up there.. in weightlessness. Oh and if those names sound familiar, it’s because Tom Marshburn will become an astronaut six years later, and at the time of this recording Joel Montalbano is the program manager for the International Space Station. But before that, they were bootleg Hans and Franz.

And that relationship with the ground support team continued even after Wolf himself was back on the ground. We’ll, of course, talk about this in more detail in just a few episodes, but on January 24th, 1998, just ten days after Wolf’s EVA, Space Shuttle Endeavour arrived to perform the final NASA crew swap on the station. Wolf returned home on Endeavour and began re-adapting to life on Earth. But the mission doesn’t end when you land. For months after touching down at the Kennedy Space Center, Wolf’s schedule was jam packed with medical exams, engineering and science debriefings, meetings with scientists who had experiments on Mir, and of course, engaging with the public. There through all of it was Chris Flynn, Wolf’s flight surgeon. He’d pick him up in the morning, and on the way to work they’d stop at a local shop to grab coffee and a donut, finally able to allow the Earth thoughts in. Between training in Russia, the stay on Mir, and the intense after-mission duties, Wolf was essentially gone for around two years. He had to pick back up neglected hobbies and day to day chores, relearn his neighborhood, noting new housing developments, stores that had opened and closed. It kind of puts in perspective why people leave this dream job. Wolf was a bachelor so it was a little easier to literally disappear off the face of the Earth for a couple of years, but like Dan Tani told us in his interview, that gets a lot harder when you have a family.

For now, Dave Wolf could focus on settling back into day to day life, enjoy his Earth thoughts, and turn his attention to his next assignment.

Next time, we roll back the clock a bit to visit the one shuttle mission that took place while Dave Wolf was on Mir: STS-87. We’ve got science to do, and a stranded SPARTAN to rescue!

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass.