Episode 172: NASA-6 Part 1 - Infinite Job List (Wolf on Mir)

Table of Contents

After much deliberation on the ground, the verdict is that Dave Wolf will indeed remain on Mir for his full mission! So what does he do while he’s up there? And who’s that in the window??

Episode Audio #

Photos #

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 172: Long Duration Mir Flight NASA-6 Part One: Infinite Job List

Last time, we covered the seventh space shuttle flight to dock with the Russian space station Mir: STS-86. The flight was notable for a few reasons depending on who you ask. To space trivia buffs, it was Space Shuttle Atlantis’ last trip to Mir, with other orbiters taking over as Atlantis entered an extended maintenance period. To Mike Foale it was a ride home after a long and trying mission. To Dave Wolf it was a ride to work, hopefully not to kick off a long and trying mission. To Scott Parazynski it was his first time donning a spacesuit and heading out into the black. For Wendy Lawrence it was a dream denied for want of a few inches of height. And to NASA Administrator Dan Goldin it was a gamble that the hard work of Mir’s crew and ground controllers had resolved its ongoing issues; the future of the partnership between NASA and Roscosmos, and thus the International Space Station, depended on it. That’s because after much drama swirling around on the ground, the decision was made that yes, NASA astronaut Dave Wolf would indeed remain on Mir to serve out his full mission. Yes, there were safety concerns, but there are always safety concerns in space. Everyone from Dan Goldin to Dave Wolf and everyone in between had examined the risks and the rewards and determined that this was a task worth doing. NASA would stick with the partnership even when it wasn’t easy after all. Today we’ll learn about Wolf’s four month stint on Mir, which, it turns out, were a little easier than his predecessors. At least the last two.

But first, how did Dave Wolf even get here? Of course, we already know Wolf from his 1993 flight on STS-58, the second Space Life Sciences flight, but what has he been up to since? Well, at least part of what he’s been up to has been living and working in Russia, training to become the final NASA astronaut to live on Mir. The plan was that Wolf would fly after Wendy Lawrence’s upcoming stint and would likely launch some time in January of 1998, becoming the last astronaut to live on Mir. Of course, he was also technically Wendy Lawrence’s backup, theoretically ready to swap places and fly in her stead, but crew swaps like that were exceedingly rare so it’s not like–oh. Oh he is replacing Wendy Lawrence? That changes things.

So it was that while hard at work in Star City, keeping an eye on his expected launch date in around six months, Wolf sat down for a discussion with fellow astronaut the manager of the Shuttle-Mir program: Frank Culbertson. Wolf had been intending to ask Culbertson if there might be a chance for him to squeeze in some Russian EVA training during the upcoming six months. Instead, Culbertson asked how Wold would feel about heading to space.. in one month. Wolf, of course, immediately accepted and was thrown into the metaphorical pressure cooker as he rushed to finish his training.

But that metaphorical pressure cooker was actually a little bit literal, with Wolf’s body run through a gauntlet of unusual atmospheric pressures. I’ll explain. The reason Wendy Lawrence could no longer stay on Mir was that she was too short for the Russian space suit. Previously there was no need for her to wear one, but after the Progress collision it was deemed necessary that all long term Mir crew members be able to perform a spacewalk. So while Wolf did get his wish of undergoing Russian EVA training, he got a version where they squeezed about six months of work.. into three weeks. Almost every day, Wolf was in the Russian neutral buoyancy pool, learning how to operate safely in space using the Orlan suit. The compressed timeline was possible because he had already undergone NASA’s EVA training, allowing him to only focus on the differences between the two spacesuit systems, but it was still a grueling and physically demanding schedule.

When he wasn’t in the bottom of the EVA training pool or studying like crazy for his exams, Wolf was in an airplane doing training in weightlessness or even in vacuum chambers, trying an Orlan suit in an actual vacuum. All these rapid and extreme changes in pressure were a cause for concern from his flight surgeon, Chris Flynn, as he relayed in an oral history interview. Flynn’s job as Wolf’s flight surgeon was to keep the astronaut healthy, both physically and mentally, such that he would be able to best accomplish his mission. Part of this was just because Dave Wolf is a human being who deserves to be healthy and happy just like anyone else, and it was important to have a dedicated advocate watching out for him. But another part was that at this point Wolf was a valuable national asset. A lot of time and money had been invested in Wolf’s training and a lot of time and money would be squandered if he were to be injured and unable to fly to Mir. So Flynn kept a very close eye on his training.

In yet another example of the culture clash between Americans and Russians in Star City, Flynn ruffled some feathers by insisting that he be allowed to see the diving charts being used while training in the pool, and the depressurization rate used in flight and vacuum chamber testing. These charts combined the pressures Wolf was exposed to, and the durations he was exposed to them, and calculated the amount of time needed to depressurize or repressurize. Wild swings between the raised pressure of the pool and the lowered pressure in the plane and vacuum chamber could lead to Wolf getting the bends, a painful and dangerous condition where nitrogen that had been forced into his blood by high pressures would begin to form bubbles in lower pressures. It was a valid concern.

But from the point of view of the Russians, they were somewhat appalled by this young doctor seemingly hassling and double guessing the Russian leaders in the field, men who had been around since the Gagarin days. But just as NASA had to simply accept that sometimes Russia did things differently, Russia had to reciprocate, and after working through the language barrier, they begrudgingly involved Flynn more in the process, tweaking the procedure to be less demanding on Wolf’s body. Teamwork! Compromise! The good stuff!

Wolf made it through his pressure gauntlet intact, blasted through his accelerated training, flew back to the United States, cleverly placed some meetings and travel on his schedule that may or may not have existed in order to carve out a few days for himself to have a breather and enjoy Earth. And before he knew it, he was at Mir.

As we’ve established, a critical part of every long duration stay in the handover. John Blaha and shown Jerry Linenger how life on Mir actually worked, Linenger showed Mike Foale, and now Foale was showing Dave Wolf. Asked about Foale’s advice during the handover, Wolf said quote “Well, handovers are very important. He had a lot of good advice. He showed me how to work the toilet properly, along with a myriad of critical information.” Always good to start with the toilet.

But Foale also passed on some less obvious advice, including the importance of attending the communications passes. Since the Mir program preferred to rely on ground stations located within Russia, comm passes were typically around 10 minutes long and would happen about once every rev, or about 90 minutes. Foale stressed that Wolf should prioritize attending these passes since it helped to integrate with the crew and the ground support teams, even if that was sometimes a challenge because it might interrupt long-running experiments. This advice stuck out to me because Jerry Linenger seems to have almost entirely abandoned the comm passes, deeming them to be a waste of time. And while Linenger seems to have gotten along fairly well with his Russian crewmates, Foale seems to have done quite a bit better, becoming a trusted and critical part of the team, especially during the chaos surrounding the Progress M-34 collision.

Advice relayed, Foale then hopped across the Docking Module to Atlantis, which soon departed the station. Wolf compared the view of Atlantis backing away from Mir as akin to being dropped off at summer camp and watching your parents’ station wagon recede into the distance. He was here now, and he was excited to get started.

Along with various advice on how to live and work on Mir, Foale also helped Wolf out by working so hard with his Russian crewmates to get the space station back in working order over the previous months. While Foale was still able to get some science done, his stint on Mir had been primarily taken up by recovering from the disastrous collision of Progress M-34. But by the time that Wolf had arrived, all modules other than Spektr were powered and working, and there was enough electricity to begin working on science again.

Also key to Wolf’s success was Wendy Lawrence. As Wolf himself went out of his way to mention, Lawrence’s contributions early in the mission were critical. Since up until very recently she had been the prime crew member for this flight, she knew the experiments inside and out. While Atlantis was still docked she had worked to get all the experiments set up and started, ensuring that Wolf could start with productive science right off the bat. So while Lawrence would be heading back with Atlantis, she was still an essential part of the mission.

As always there were a variety of experiments in a variety of fields being performed with a variety of involvement levels by Wolf. The easy ones were the long duration passive experiments: material samples on the exterior of Mir, radiation sensors inside the station, closed-up dewars of protein slurries that were gradually becoming crystals, and so on. There were also experiments on Wolf himself, examining how the months of time in weightlessness were affecting the astronaut’s body. There were also more refined crystal experiments, taking advantage of the vibration isolation mount that we’ve seen fly on the shuttle on previous episodes. Sensitive accelerometers on the mount would detect minute vibrations in the space station from stuff like onboard systems or crew members running on the treadmill. The mount’s controller would then react to those vibrations, using precise motors to physically adjust the mount, leaving the environment inside undisturbed. The result was that the station essentially vibrated around the crystal. But Wolf’s favorite experiment was one that took advantage of the microgravity environment to build 3D tissue cultures. Though he may have been a little biased since he invented it.

Yes, before he was an astronaut, Dave Wolf was a medical doctor and NASA researcher. And among other things, for years he was the lead for this space-bound tissue culture experiment. It was just a weird stroke of luck that nearly ten years later both he and the experiment actually flew and somehow flew at the same time on the same mission. I mean this wasn’t even supposed to be his mission. I’m no expert on this, so if any biology-minded listeners would like to confirm or refute this, please send me an email, but on Earth when scientists grow tissue samples of different types of cells, they would grow them on a flat Petri dish, essentially in two dimensions. But that’s not typically how living creatures work. I don’t know about you, but I’m pretty 3D. But how do you grow cells in a 3D structure when hampered by gravity? Well, the answer is that you remove gravity from the picture.

Over the course of NASA-6 and NASA-7, the experiment grew samples of breast cancer cells, nerve tissue, kidney tissue, and lymphocytes, all taking advantage of the weightless environment to grow the tissues in three dimensions, just like would be found in the body. It was unique and important research that could only be done in space, and Wolf was the perfect guy to be operating it.

Of course, science was only part of the picture. Yes, NASA was pouring a lot of resources into the Shuttle-Mir program in part for the scientific return from the various experiments being flown on board Mir, but also for the more intangible goal of learning to better work with their Russian partners. The ISS was going to be a difficult and expensive undertaking. The more that could be done to ensure success between the American and Russian crew members, the better.

Part of this was accepting and embracing cultural differences. As one example.. Russia had very different approaches to handling day to day problems. Astronauts were encouraged to speak up early and often, pointing out potential issues as they came up and easily involving crewmates and the ground. It would be a faux pas not to point out problems. With the Russians, it was different. Pointing out a problem might be met with silence or disdain. Russian crewmates also had less of an air of politeness and teamwork, at least in the ways that Americans are used to. Wolf quickly learned to expect to be treated harshly and firmly. For the Russians, if you’re on Mir you’re a professional, you have a job to do, and you don’t need to be coddled. And actually, Wolf pointed out that not only did he come to expect this treatment, he preferred it. It showed that he was being treated as a fellow crewmate and not being patronized as some pampered outsider who couldn’t handle real work.

The Russians also weren’t likely to thank you or encourage you for doing something that they considered a basic part of the job. If it was required of you, why thank you for it? So if you actually got a pat on the back from a Russian crewmate, you knew he really meant it. We’ll talk about this spacewalk in more detail in Part 2 of this episode, but after Commander Solovyev and Wolf came back inside from an EVA, Solovyev told Wolf “good job” and Wolf considered it a high point of the mission.

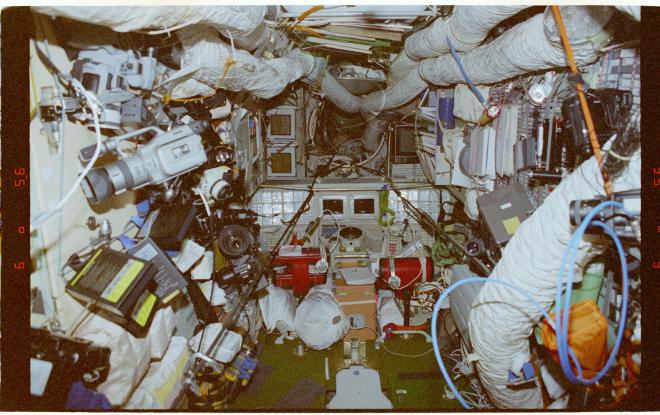

Like Foale before him, Wolf was eager to be an accepted member of the crew. Something a lot of these NASA Mir astronauts seemed to dread was the idea of being treated like a guest at a resort instead of a comrade in the trenches. As such, after observing Pavel Vinogradov spend five or six hours sopping up condensed water using rags, Dave Wolf swooped in and told him that he never needed to worry about it again, that he would handle it. Wolf told Vinogradov had more important things to do like continuing to repair the station. But just like Foale, Wolf didn’t fully appreciate what he had signed up for. From that day on, for 4 to 8 hours, nearly every single day, Wolf would float over to the Kvant-2 module, slip behind a particular wall panel, and squeeze his body in among the equipment and cabling until he reached his destination: the Elektron oxygen generating system, buzzing with electricity. Once there he would begin sopping up blobs of frigid water that were typically the size of a grapefruit or a bowing ball, but could sometimes reach the size of beach balls. The issue was that the heat exchangers on the Elektron system were cold, and Mir was both hot and humid. The humidity would condense on the heat exchangers, and with no gravity to pull the water away, it would just grow and grow as a big blob. The work was tedious and uncomfortable, but it had to get done, and so Wolf did it.

In addition to mysterious blobs of gross water, another thing this mission had plenty of was spacewalks. During Dave Wolf’s stay, Mir would see four EVAs and one IVA.

First the IVA. Again, since this is sort of a weird concept, I’ll remind you. Instead of an extravehicular activity, this was an intravehicular activity, with the crew sealing off all the hatches in the node leading to other modules, depressurizing it, and heading into the damaged Spektr module. Just like Foale before him, Wolf waited in the Soyuz in case something went wrong and the crew were forced to evacuate. The goal of this IVA was to replace the hatch that sealed off Spektr from the rest of the station, as well as regain access to some electrical cables that controlled the slew motors on Spektr’s three remaining functional solar arrays. As it stood, the solar arrays were connected to the station’s power system but the only way to point them in a desired direction was to literally go outside and poke at them with a big stick. So ever since the accident they had just been pointed in a direction that was vaguely good for most of the time. Regaining the ability to actually point the arrays would be a real boon to the station.

The IVA proved to be challenging, with the cramped environment already making things difficult due to the bulky space suits and general clutter, but also one of the three control cables turned out to be stiff and difficult to work with and their tools proved inadequate to the unusual task. Even after dipping a bit into their emergency backup resources, Solovyev and Vinogradov were unable to connect the third cable and were finally forced to accept that two outta three ain’t bad. After around six and a half hours in a vacuum, the duo repressurized the node, ending the internal spacewalk. With their repairs now allowing Spektr’s solar arrays to track the Sun, Mir’s power capability was increased by 15-30%.

Two weeks later, the Russian crew again suited up, but this time they headed outside; how novel. While the Russians were outside, Wolf would remain inside and be responsible for keeping an eye on space station systems and for issuing computer commands related to the goals of the spacewalk. Wolf compared to look he got from Mir Commander Solovyev to the look that a kid gets from their dad before taking the car out to drive on their own for the first time. I’m sure Solovyev believed that Wolf was up to the task or he never would have trusted him with the responsibility, but, still. The station was his baby.

Before work really got started on this EVA, Solovyev took a moment to commemorate a special anniversary. On October 4th, 1957, the Soviet Union changed the world forever. It was on that day that a small metal sphere named Sputnik was lofted into the heavens atop a modified ballistic missile, becoming the world’s first artificial satellite. An artificial moon. Well, on November 3rd, 1997, just over 40 years later, as Anatoly Solovyev used one hand to hold onto the 100-plus ton space station, he used the other to release a small replica of that benign beeping beach-ball, and watched it sail off into the void. We’ve come a long way since then. It’s kind of incredible how quickly things can change when we decide to set our minds to something.

With that poetic moment out of the way, Solovyev and Vinogradov got to work on their actual task for the day. Well, I think this was the task for the day. All of my sources sort of lump this EVA and the next one together into a single thought, so we’ll just do our best.

The spacewalkers traversed from Kvant-2, where the airlock is located over to Kvant-1. A solar array mounted to Kvant-1 had deteriorated to the point that it was only providing a trickle of power. The Russians dismantled the structure, folded it up, and mounted it to the exterior of the base block for temporary storage. They also installed the exterior components another CO2 scrubbing system on Kvant-1.

In his letters home, which I believe were posted on NASA’s website as he sent them down, Wolf wrote about how he could track the positions of the Russian spacewalkers by the sounds of them clanking against the exterior hull of the station. Occasionally would of them would suddenly appear in one of the windows and startle him, which I imagine was the intended effect!

After completing their work, the Russian duo headed back to the airlock where they ran into a minor snag. The airlock door had been damaged years ago but some space-based repairs by an earlier crew had fix it.. until now, apparently. The hatch mostly sealed, and even indicated that it was closed, but it was letting an unacceptable amount of air leak out. Luckily, this airlock was designed with a second, smaller, compartment that could be used as a backup. We’ll be learning a little more about this later but for now we can just say that after 6 hours and 5 minutes, the EVA ended in the inner compartment.

Just three days later, Solovyev and Vinogradov headed back outside again to complete the solar array job. Or maybe to troubleshoot the job that was left unfinished, again, the sources sort of blend these two walks together. With the old solar array removed from Kvant-1, that spot was now clear to install a new solar array that had been delivered all the way back on STS-74, almost exactly two years earlier. Remember, this is the one that NASA and Russia built together and was delivered alongside the Docking Module. The spacewalkers were able to get the large array into position but when Wolf punched in the commands to deploy it, something went wrong. The structure partially deployed.. but then stopped.

Wolf would later mark this as a particularly stressful moment of the mission, with him suddenly having to work with the Russian control center to improvise a new procedure and punch it into Mir’s computer, with limited communications, limited time for the spacewalkers to be outside.. and all in Russian. By retracting the motors, restarting the sequence, carefully extending one segment at a time and keeping an eye on the power flowing to the motors, he was ultimately able to get the array to successfully deploy, adding still more power to the station’s electricity budget. Between the Spektr arrays and now Kvant-1, Mir was really starting to crawl out of its power woes.

As Solovyev and Vinogradov came back inside they took some time to inspect the seal on the airlock’s outer hatch, including taking some photos and video. They noted that the rubber gasket seemed to have some damage and that the door’s mechanism was not moving smoothly. Once again they ended the spacewalk using the inner compartment, after 6 hours and 19 minutes outside. Once back inside the station, the three-man crew were delighted that they had overcome the problem with the new solar array, and celebrated with high fives, which of course sent them tumbling backwards. Newton’s laws care not for your high fives.

With the first set of EVAs complete, life onboard Mir returned to its usual routine. For this crew, that routine involved work: lots and lots of work. Wolf recalled working 9 AM to midnight nearly every day of the mission, except for taking the afternoon off on Christmas and a couple of Sundays. This again seems to stem from the desire of the American crew members to make sure that they weren’t taking it easy at the expense of their Russian colleagues, which is a commendable attitude. Wolf would see Solovyev and Vinogradov busting their butts working to keep Mir alive while also slowly upgrading its systems and wanted to do his part. So despite putting in 8 or 9 hours a day on his science tasks, he also did what he could to help with the overall station. As he discussed in an oral history interview, sometimes that meant taking another job off the job list at ten at night, and it was an infinite job list.

One important part of getting into this groove was a mental discipline that all astronauts seem to share. Wolf talked about making a conscious effort to not allow Earth thoughts to wander into his mind. It was important that he didn’t allow himself to start pining for his Earth routine of little things like driving to the store to get a cup of coffee, or that would just open the flood gates. To be honest, I wonder if this is part of what made John Blaha’s stay on Mir so difficult.

But at the same time, while it was important to live in the moment and be a resident of space, that connection to Earth was crucial. Wolf maintained relationships with his friends and family via email, even expanding his circle of pen pals to include friends he had lost touch with a bit. So to his surprise, while training and the mission itself had been a strain on relationships, it also helped others flourish.

In an further connection to Earth, Wolf became the first American to vote from space. John Blaha had run into this issue on his flight, so election officials worked with NASA to come up with an email-based system for the most absentee of ballots. Wolf said that the act of voting showed how space was becoming a place to live, so unlike a short shuttle flight you actually had to pay attention to life on the ground.

He also found himself unusually affected by movies. Something about seeing people on Earth interacting with Earth things had a surprising impact on him, far more so than the same movies when viewed on the ground.

As the days ticked by, Wolf also joined a small group of only four other Americans who had rung in the new year from orbit. If you want to guess the others on your own you’ve got about five seconds to frantically pause the podcast before I reveal that the others were.. John Blaha, of course, just the previous year, but also the crew of Skylab 4: Gerry Carr, Ed Gibson, and Bill Pogue, who celebrated the start of 1974.

All in all, Wolf’s mission was clearly going quite a bit more smoothly than those of Foale and Linenger. Science was getting done, nothing was crashing into stuff, and Wolf was in a good groove mentally. Next time, Dave Wolf will finally head outside on his first EVA, but will get a little more excitement than he bargained for.

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass.