Episode 168: NASA-5 Part 2 - The Specter of Progress (Foale on Mir)

Table of Contents

New episode! In part 2 of our NASA-5 coverage, we’ll find out what the crew did next after surviving the immediate crisis following the Progress M-34 collision. Also, we’ll wonder why there’s so much water in Mir’s walls.

Episode Audio #

Photos #

Post-Flight Presentation #

Here’s that crazy video of Oleg Kononenko hacking away at a Soyuz with a knife in 2018, which we’re using as a substitute for footage of Solovyev doing something similar outside Spektr. The translator might be the best part.

Spacewalk Footage #

I also found this brief clip of Solovyev and Foale outside on their EVA, shot through Mir’s windows by Vinogradov.

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 168, Long Duration Mir Flight NASA-5 Part 2: The Specter of Progress

Last time, we covered the first part of astronaut Mike Foale’s four and a half month stay on the Russian space station Mir. We only made it to the fifth week of Foale’s journey, however, as both our narrative and the entire Mir space station felt the impact of Progress M-34. As part of a rendezvous test gone awry, the resupply spacecraft crunched into the Spektr module’s solar array, tore a hole in the hull, and sent the entire station into a slow but uncontrolled tumble, before itself tumbling off for an eventual deorbiting. When we left our intrepid crew of Vasily Tsibliyev, Sasha Lazutkin, and Mike Foale, they had just wrapped up 30 sleepless hours of crisis management, sealing off the leaking Spektr module and orienting Mir in an attitude that ensured a reliable supply of electricity. After sleeping in shifts and catching their breath for a bit, the natural question was.. what’s next?

The crew had made it through the immediate crisis unscathed, but there was still a lot of work to do before anyone would be returning to life as normal. The first lengthy task was to slowly recharge all of the onboard batteries. To do this, the crew would remove paneling from the sides of various modules to access the large batteries, disconnect them, and bring them over to the base block for charging. Even under nominal conditions this would be pretty onerous, but with the station even darker than usual due to low power, and with the usual level of onboard clutter, it was a real challenge. Before you could even get to the panel you had to clear a workspace as well as clearing a good path to bring the bulky battery to the base block. Though Foale noted that Kristall still had some illumination thanks to the inclusion of the greenhouse experiment, the one that Shannon Lucid had grown wheat in. For some reason despite being physically located in Kristall, the experiment was powered by the base block. Go figure.

Recharging the batteries was tedious, but at least it was fairly straightforward. What was not at all straightforward was the plan being developed to attempt to rescue the stricken Spektr module.

Rescuing Spektr would be a worthwhile cause for a number of reasons. In a sort of vague order of most important to least important as judged by me, we can start off with the fact that Spektr’s exterior sported some nice big solar arrays. OK, one of them wasn’t so nice anymore, but there were still a bunch that could work fine. With electricity always at a premium on Mir, restoring the flow of power from those arrays would make a huge difference. You don’t even need to have hard numbers to see what an impact the disconnecting of Spektr’s solar arrays made. Load up a photo of Mir and do a count of the large solar arrays. By my count there are ten, with four of them on Spektr. And on top of that, most of the other large arrays between five and nine years older than the ones on Spektr and so had degraded over time, delivering less power. Spektr actually had two of its solar arrays added very late in the process specifically to help deal with the diminishing power being delivered by the rest of the station’s solar panels. So the damage and disconnection of its panels was a really big deal.

Second, Spektr was one of the primary modules for doing scientific work inside the station. In addition to various Earth observation instruments, it was also a main location for experiments performed by NASA crew members. This makes sense because NASA actually funded the final development and launch of Spektr as an early part of the Shuttle-Mir partnership.

Third, this is just me speculating, but because of that NASA funding, I would imagine at least part of the desire to save Spektr was in an effort to save face. NASA had joined the Russians to do this project together, forked over a boatload of cash in order to help get more science done, and then Russia has essentially crashed a space truck into it. It wasn’t exactly the image that a country that was very proud of its space program wanted to portray.

And last and actually least.. well, Mike Foale’s stuff was in there! Spektr had been where Foale slept, so his personal effects were trapped in the depressurized module and it’d be nice to get them back. Also, what a weird problem to have..

OK, so I think we can agree that attempting to save Spektr was a good idea, but how could it even be attempted? Well, you’ve heard of EVAs, or extravehicular activity. Now it’s time to plan an IVA: intravehicular activity. The plan, in short, was for Tsibliyev and Lazutkin to don their Orlan space suits and enter the depressurized Spektr, hoping to find and repair the leak in the hull and reconnect the module’s solar arrays to the station’s power system. The first goal seemed somewhat unlikely given the small size of the leak and the large size of the module, and with all the panels and systems and equipment in the way. But the second one was actually pretty doable. There’s just one problem. How would they connect the power cables that were inside Spektr to the overall station when in between them was an airtight hatch?

The answer arrived a little less than two weeks after the collision with Progress M-34 with the arrival of Progress M-35. Among other things, this resupply ship contained a hastily manufactured adapter plate for the hatch that was sealing off Spektr. Built into this adapter were a number of electrical hookups for both sides of the hatch. So if the crew could get into Spektr, install this special hatch, and connect the power cables to it from the inside, then when they were done and everything was sealed back up, the former entrance to Spektr would now have some electrical connections on the outside, allowing its solar panels to be used again. This was a relatively straightforward concept, but in practice it would be difficult to execute. Tests needed to be performed to see if the suits could even maneuver around inside the confines of the module, the crew needed to practice working with this adapter plate that they had never trained for, and every cable snaking its way through the node needed to be disconnected so all other modules could be sealed. The crew got to work.

While the crew prepares for the IVA, let’s take a brief detour to look at something else that arrived in Progress M-35. Along with the adapter plate, shelf-stable food and supplies, fresh snacks, and new family photos for Foale, was a European experiment named MAPS. Now, I must admit that I have been completely unable to find anything about MAPS other than what is mentioned in Mike Foale’s oral history interview. I can’t even find what it stands for. It seems that the combination of using a common English word for its name and the fact that an identically named experiment also flew on the ISS makes this unsearchable. But I’m mentioning it because it really made me laugh and I think highlights the disconnect between ground controllers and the crews actually flying Mir missions, especially under these circumstances.

MAPS was a big cylinder that Foale compared to the size of a desk. Or more importantly, it was barely smaller than the passageway between station modules.. if there were no cables in the way. Clearly, engineers on the ground had dug up the specifications for Mir, looked at how wide the passageways were and how big the modules were, and designed their experiment.. forgetting that those specs were for when the station was empty. Part of why I find MAPS so funny is that even Mike Foale isn’t entirely sure what it was, why it was there, or what it was supposed to do, but he knew that while they eventually wanted to get it outside, for now the ground wanted to park it in the docking module. So the crew had to carefully remove cabling and clear a path around various equipment and supplies, moving it all the way from the Progress, through Kvant-1, through the base block, into the node, into Kristall, and finally into the Docking Module. Oh and be careful, because for some reason this giant cylinder is stuffed full of ammonia. So don’t break it.

To top off the MAPS farce, after being a massive distraction to a crew that really needed to focus on the task at hand, it remained in the Docking Module forever, presumably finally making it outside as the Docking Module disintegrated around it during Mir’s reentry around four years later. Oh well.

Back to our IVA preparations. They’re actually not going great. Commander Tsibliyev, who had been under juuuust a little bit of stress, felt his heart skip in a funny way and an EKG soon confirmed that he had a mild arrhythmia, disqualifying him from the strenuous IVA. However, in a twist that truly demonstrated just how much confidence the Russians now had in Mike Foale, he was asked to substitute for Tsibliyev. Foale had some concerns about whether he could do the novel task with a lack of dedicated training, but got to work preparing so he could do his best.

But just a few days later, it turned out to be a moot point. In order to make the IVA itself go more easily, Lazutkin had been working in the Node, disconnecting as many cables as possible ahead of time, so there would only be a few left to deal with on the big day. It was a big task, disconnecting hundreds of cables in a specific order. Unfortunately, he got one cable wrong, disconnecting a data cable between attitude control sensors and the attitude control system itself. He quickly plugged it back in and for a moment thought maybe nothing had come of it.. but when the master alarm triggered he knew he had screwed up. Lazutkin had been under an extraordinary amount of stress and it was a simple mistake to make, but it was a mistake nonetheless. When the data cable had become disconnected, the station no longer knew which way it was pointed. So rather than risk being in some crazy death-spin without even realizing it, the computer shut down all the gyrodines. This is already not great but then you remember that the conservation of angular momentum exists: when the gyrodines shut down, all that angular momentum had to go somewhere. So not only was Mir now not controlling its attitude, it was slowly spinning again.. and spinning away from the sun. They were back in the same crisis they had encountered immediately after the Progress collision.

During the lengthy effort to recover Mir’s attitude, the crew made a somewhat distressing discovery. They decided to start powering up the Soyuz, just in case the situation worsened and they were forced to abandon the station. But it turns out that this wasn’t possible. In order to turn on the Soyuz, its power supply needed to be switched from Mir to the Soyuz itself.. but in order to do that, the Soyuz needed power.. from Mir. So basically, you couldn’t turn on the Soyuz if the station was dead. Even if its batteries were fully charged, switching from Mir power to Soyuz battery power required power from Mir. This raises some obvious questions about its utility as an emergency lifeboat since it apparently meant that station power was required for an evacuation, greatly limiting the number of scenarios allowing the crew to escape. But after a bit, just by chance, Mir eventually rotated back onto the Sun enough that the crew had sufficient power to turn on the Soyuz. Foale sort of downplayed this later, saying that he thought the media made too big of a deal out of it, but for 13 minutes there the crew was simply stuck. And as we learned on Linenger’s flight, a lot can happen in 13 minutes on Mir.

Anyway, the combination of Tsibliyev’s arrhythmia, the attitude crisis, and a clearly over-stressed and overworked crew lead the ground to decide to postpone the IVA until the next Russian crew arrived in a couple of weeks.

That new crew arrived on August 7th aboard Soyuz TM-26. The spacecraft only contained the two Russian crew members, with no short term crew member joining them. Originally a French astronaut was intended to fly with the crew but due to the ongoing trouble caused by the Progress collision, his flight was delayed. This new crew is going to be with us for a while, so let’s meet them!

Commanding Mir for this next mission was Anatoly Solovyev, who is actually a familiar face. He caught a ride to Mir back on the first shuttle docking flight: STS-71. Back then, I decided to not get into his backstory since he was just flying as a passenger, but I suppose now that he’ll be a central figure it’s time to properly introduce him. Anatoly Yakovlevich Solovyev was born on January 16th, 1948 in Riga, which was then part of the Soviet Union but is now the capital of Latvia. He spent his late teens as a general laborer and metalworker before heading back to school. He graduated from the Lenin Komsomol Chernigov Higher Military Aviation School and spent the next few years serving as a senior pilot and group commander in Soviet armed forces. In 1976 he joined Cosmonaut Group 6 and began three years of general training. Solovyev apparently couldn’t get enough of space because he flew on missions in 1988, 1990, 1992, and 1995, racking up over 450 days in low Earth orbit even before adding nearly 200 more on this flight. Well he’s back for one last time on this, his fifth of five flights.

Joining Solovyev was Flight Engineer 1 for Mir EO-24: Pavel Vinogradov. Pavel Vladimirovich Vinogradov was born on August 31st, 1953 in Magadan, in the far East of Russia. He graduated from the Moscow Aviation Institute, specializing in booster design, going on to become a computer systems analyst. He spent the next six years working in software development for a variety of things surrounding recoverable space vehicles. In 1983 he began working for Energia and actually helped develop the Buran, which only flew the one time, and the Soyuz TM, which he just launched on. I actually think a pretty cool thing about the Russian space program is that it seems like a fair number of cosmonauts are just engineers who were working on the space program and then one day found themselves riding in the spacecraft that they had been working on. In 1992 he became a cosmonaut and has served in a couple of backup roles, but this is his first of three lengthy flights.

The combined crews spent the next week doing a handover, and on August 14th, Tsibliyev and Lazutkin said their goodbyes, climbed aboard Soyuz TM-25, and departed for a return to Earth. Vasily Tsibliyev and Sasha Lazutkin’s six month stay in orbit contained some of the wildest and scariest moments in all of human spaceflight history. There was a nearly catastrophic fire, a near miss from Progress M-33, and a severe collision from Progress M-34, completely changing the nature of life on Mir. But despite all that, they persevered. Mir wasn’t abandoned, nobody was killed or even seriously injured, and while Mir would never be the same after the crash, it continued to function and still had years of useful life left ahead of it. Neither man would fly in space again, so we’ll bid them farewell, and hope that their next assignment is a little less stress inducing.

The next day, Solovyev, Vinogradov, and Foale piled into the remaining Soyuz and undocked from Kvant-1 so they could reposition the spacecraft on the node’s docking port. Along the way, Solovyev brought the Soyuz near the damaged Spektr module, and Foale squirmed into the orbital module at the front of the Soyuz to take shoot some photos and video of the damage. The hope was that by analyzing this footage, clues about the source of the leak might be revealed. One quick trip around the station later, Solovyev docked the Soyuz at the Node and the crew got back to work.

A few days later, Progress M-35, which had been told to take a hike while both ports were taken up Soyuz TM-25 and -26, returned and moved in to dock with the Kvant-1 port. Despite its trouble-free docking the first time, for this approach M-35 decided to extend the streak of troublesome Progress dockings. During the last 100 or so meters, the rendezvous system failed, requiring Commander Solovyev to take over with the same TORU control system that Tsibliyev had used for both manual Progress docking attempts. But this time, the system was actually being used for the intended purpose. Progress M-35 was already most of the way there and just need a little help closing the final gap. So despite the hiccup, it re-docked with no major drama.

Once the new crew had settled in, it was time for the IVA. They donned spacesuit gloves and practiced the procedures with the adapter plate while still in a nice and easy pressurized environment. They also worked out solutions to some potentially sticky situations that could arise if things went wrong. For example, what if something went awry when swapping out the Spektr hatch and it wasn’t possible to repressurize the Node? Since the Node connects all the other modules together it wouldn’t be possible to access any other part of the station and there would be no choice to abandon Mir. OK, that wouldn’t be great, but that’s one reason why the Soyuz was docked to the Node. If the worst happened, the spacewalking crew could climb into the Soyuz and head home. Except hang on a second, Mike Foale is in there. With a fresh Russian crew on board, Foale had been bumped from the Spektr spacewalk and so would wait inside the safest place on the station and their only ride home: the Soyuz. But Foale didn’t have a space suit, so how could the Russian crew enter from a vacuum? Ah, this is pretty easy thanks to the design of the Soyuz. Foale would wait in the pressurized Descent Module and if necessary, the Orbital Module could be vented, the Russian crew could get in, close the hatch, and repressurize. It would be a tight fit but it would be doable.

Except there’s another wrinkle in this plan. The hatch to the Soyuz can’t be opened from the outside. Because of course it can’t, otherwise this would be too easy. Hmm. Well, Foale could just head over and open the door, right? No, because the Orbital Module would be depressurized and he doesn’t have a suit. So what to do? This is great, what they did was start out with Foale moving from the Node and into the Orbital Module, closing the hatch behind him. Once that was done, Solovyev and Vinogradov were left in the Node in their spacesuits, and vented half the atmosphere out. Foale then undid the latches for the Soyuz hatch. This sounds crazy at first, but the hatch was a plug-like design. So with the full atmosphere on his side and the half atmosphere on the node side, the hatch was unlatched but wedged into place. He then moved into the Descent Module and closed that hatch while he waited for the guys to finish the IVA. In the meantime, the Node and Orbital Module were fully vented. With no more pressure holding the hatch shut, it was free to swing open and let the Russian crew in.

This plan actually worked fine but with one last little complication that Foale specifically pointed out as being illustrative of the differences between the NASA and Roscosmos approaches. As the Russian crew vented the Node down to half atmosphere, Vinogradov noticed that his glove was leaking. It wasn’t an emergency but it also meant that they couldn’t proceed with the spacewalk. In response, they just repressurized, Solovyev climbed out of the back of his Orlan suit, helped Vinogradov fit on a new glove, climbed back into his suit, vented to half atmosphere again, and confirmed that the glove was ok before proceeding with the spacewalk. Foale was struck by the no nonsense “shrug and fix it” sort of response to the leaky glove, speculating that NASA likely would have at least called the EVA off for the day until the problem could be investigated. But as a great man once said, “this is how we fix problem in Russian space station.”

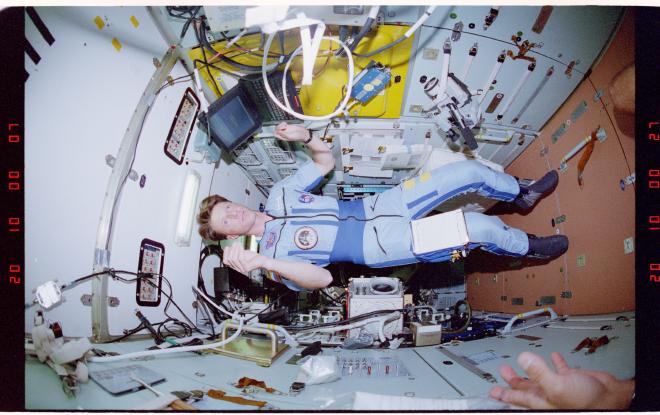

Once the IVA actually got going, it went nice and smoothly. Upon entering the module they found that much of the equipment was coated in frost and there were white crystals floating around inside. Spooky. The leak was not able to be located from inside the module, but the rewiring worked with no problems. And on the way out, Solovyev grabbed some of Foale’s stuff including family photos, his laptop, a light for an experiment, and some other odds and ends. Though I’ve got to wonder what two months of being in a hard vacuum does to a laptop. I never heard if it worked again or not. Other than the inability to find the leak, the only problem with the IVA was that solar array slew commands were not able to be passed through the adapter as was hoped. So while they now had access to any power that they generated, the panels couldn’t be rotated to track the Sun, which reduced their effectiveness somewhat. But in just a bit we’ll use a little ingenuity to improve their performance. After a five and a half hours uh.. inside, the spacewalk came to an end.

A couple weeks later it was time to put the spacesuits on again, but this time for a good old fashioned EVA. Commander Solovyev would again be climbing into his Orlan suit but this time he was joined by Mike Foale. The primary goal of this EVA was basically the same as the IVA, but coming at it from the other direction. The duo hoped to inspect the exterior of Spektr and take some close up photos and video that might indicate the source of the leak. They also brought some scaffolding that could be set up at the impact site to facilitate future repairs.

Foale’s main role in this was to operate the Strela crane, helping to move Solovyev around on Spektr. This was a pretty nice role because it actually left Foale with a lot of time to just look around and enjoy the view, which is such a rare treat when performing an EVA. But the more interesting view may have actually been over on Spektr, where Commander Solovyev, I kid you not, was hacking away at the space station module with a knife. OK, I intentionally phrased that to make it sound a little crazier, but he was literally just using a knife to slice open pieces of insulation and get a look at the bare metal underneath. And what’s wild is that this isn’t even the only time that a cosmonaut has hacked away at the exterior of a spacecraft with a knife. It’ll happen after our narrative comes to a close, but in 2018, while looking for the source of a small leak on a Soyuz docked to the International Space Station, cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko also used a knife to cut through some insulation. And unlike this Spektr EVA, there’s video footage of Kononenko really going to town on the Soyuz, so be sure to look it up.

A couple of times, Foale made the hand over hand trek down Strela to assist Solovyev, holding his feet as the cosmonaut plunged headfirst into the insulation. Despite their best efforts the source of the leak was still not found and actually never would be found, so the scaffolding was just stored nearby for potential use on another occasion. While they were out there, Solovyev adjusted Spektr’s solar arrays manually, increasing their output by about 10%. This was done manually because the new adapter plate was successful in transmitting power but did not allow them to slew the panels. So what ingenious technique did they use to manually position the arrays? Just a big pole with a hook on the end. Hey, if it works it works. On the way back inside, Foale grabbed an experiment that had been left outside by his predecessor, Jerry Linenger, closing out a six hour EVA.

After the EVA, the craziness of the mission largely died down. At this point while Spektr hadn’t been recovered, much of its power supply had, and the station was mostly functioning as intended. As the weeks ticked by there were a couple more instances of a computer crashing, leading to a loss of attitude control, but I think people sort of made a bigger deal out of this than was necessary. I don’t want to downplay it, since computers crashing and sending space stations out of control is definitely not a good thing, but I think that the description sounds way worse than it was. The station would slooowly drift off the sun and the crew would have to once again go through a arduous process of regaining power and control, but it’s not exactly all that dangerous on its own. Though that didn’t stop congressional hearings on whether the Shuttle-Mir program was too dangerous to continue running.

Much of Foale’s time was occupied by continuing to do the maintenance work that he had volunteered for early in the mission, with something like half his time being dedicated to just sopping up condensed water. This was especially a problem in the modules that hadn’t yet been fully powered up since they were so much colder, encouraging humid air to condense on their surfaces. Foale would find himself confronted by blobs of water exceeding a meter in diameter, sometimes completely immersing electronic equipment. But with spare towels, dirty clothes, and anything else that was absorbent, he slowly made progress. The final step in the drying process would be to route some of the hot air from the base block through ventilation ducts and into the powered down module. While the warm humid air would make the condensation worse at first, it would soon start to dry the module out, and equalizing the temperature made it less likely for more water to condense. The Russian ground control estimated that over the years they had lost track of seven tons of water. Foale speculated that some of that was no longer on the station, I guess leaving as air humidity with visiting vehicles and airlock dumps, but much of it was still lurking around, just hanging out in the walls. Pretty weird. But I guess now I can see why the previous crew wanted to use the Shuttle’s systems to dump some extra water overboard.

Shortly before the arrival of Space Shuttle Atlantis on STS-86, Priroda was powered on, and with that the station was basically back to full operating status. Just, y’know, minus Spektr.

As usual, we’ll cover the arrival of Space Shuttle Atlantis and Foale’s replacement in more detail when we get to those missions in the timeline, but suffice it to say that on September 27th, Atlantis docked with Mir as part of STS-86 and a little under a week later, Mike Foale said his goodbyes to the Russian crew, and soon watched Mir grow smaller and smaller through Atlantis’ windows. When Atlantis touched down at the Kennedy Space Center, it ended 144 tumultuous days in space for Mike Foale. He had endured a crisis that no NASA astronaut had encountered since the days of Apollo 13 and Skylab 2 and come through it intact. He even managed to do a fair amount of science during the flight. And in a first for the Shuttle-Mir program, this was not his last flight, so we’ll see Mike again a little down the road.

So once again we must ask ourselves what we are to make of this mission. I think it’s clear that this was the nadir of the Shuttle-Mir program. As bad as the fire during NASA-4 had been, both the crew and station made a full recovery, with Linenger’s mission ending as a success. With NASA-5, the crew were only minutes away from dying of hypoxia, or only a few meters away from Progress crashing into something less resilient and blowing out the entire onboard atmosphere all at once. Between the fire, the collision, and the computer crashes, the Shuttle-Mir program began to draw a lot of negative attention from the media and from members of congress.

But all that said.. I actually think NASA-5 is a pretty cool mission. I think the Progress rendezvous experiment wasn’t the greatest idea and could have been handled much better in order to improve its odds of success, but it wasn’t like.. completely insane to try it. And while the collision was terrible, I think having a crew deal with a close call every once in a while is probably healthy for spaceflight in general. They had to exercise their emergency procedures and verified that they actually worked, put their knowledge of physics and the station’s systems to use as they improvised a solution to the attitude problem, and it once again reinforced the lesson that spaceflight will never tolerate carelessness, incapacity, and neglect.

I also think that while nothing similar happened again during Mike Foale’s stay with NASA, it’s not the worst thing to have a member of the astronaut corps who went through something like the months long improvised recovery of Mir. That’s a unique experience that would never come up in traditional training. And if we’re ever going to leave this pale blue dot behind, we’re going to need people who can formulate and execute clever solutions to unique problems in space.

We’ll talk a little more about the investigations and hearings about Shuttle-Mir when we cover NASA-6, but I’ll mention here that Tom Stafford’s conclusion was that quote “Not only is the Mir station deemed to be a satisfactory life support platform at this time, but it is anticipated that significant operational and scientific experience is still to be gained through continued joint operations.”

I don’t know about you guys, but if it’s good enough for Tom Stafford, it’s good enough for me.

Next time, corporate needs us to find the differences between STS-83, and STS-94. They’re the same mission.

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass.