Episode 163: NASA-4 Part 2 - Close Call, Ethylene Glycol, and Secret Alcohol (Linenger on Mir)

Table of Contents

When we last left Jerry Linenger, we still had most of his mission to cover! On this episode we’ve got space-bound contraband, a LEO version of ‘crisscross crash’, and a historical EVA.

Episode Audio #

Photos #

Linenger’s Letters #

If you’d like to read some of Jerry Linenger’s letters to his son, the whole batch is available on this delightfully 90s websites. The one covering the spacewalk was April 30th.

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 163, Long Duration Mir Flight NASA-4 part two: Close Call, Ethylene Glycol, and Secret Alcohol

Last time, we watched Atlantis fade away into a bright point on the horizon as we joined Jerry Linenger for the first part of his stay on the Russian Space Station Mir. We pondered some strenuous advice from John Blaha, wondered where to find extra rolls of film in space, and welcomed a new crew. Of course, we also then stepped through each terrifying moment of the worst fire to ever break out on a crewed spacecraft in orbit. The fire had the immediate effect of nearly killing the six person crew, while also planting the insidious seeds of distrust between NASA and Roscosmos.

NASA-4 was a pretty busy mission. In fact, it was so busy that I felt the only reasonable thing to do would be to split it into two episodes. Though full disclosure, the fact that last week marked my yearly pilgrimage to the mega-sized East coast anime convention Otakon may have made that decision a little easier. If you want to hear all about me and my friends running the best darn Anime Music Video contest in the country, you know how to contact me, but for now, we’ll turn our attention back to 1997. Jerry Linenger has just survived a harrowing weightless inferno and had managed to live to tell the tale. In fact, sort of counter to my initial expectations, Linenger found himself sleeping just fine after the fire, reassured that he and his orbital colleagues could survive anything survivable. With the fire behind him, it was time to get back to work.

Believe it or not, despite everything going on, we’re still only a third of the way through the NASA-4 mission. But for three of the crew members it was time to say goodbye. About a week after the fire, Soyuz TM-24 undocked from the Kvant-1 module, bound for the steppes of Kazakhstan. For Reinhold Ewald, it was the end of a short but eventful 20 or so days in space. For Mir commander Valery Korzun, it was the last time he would see his station up close, though we’ll see him again down the line. And lastly, we’ll actually see Aleksandr Kaleri on Mir one last time, as well as on the ISS a couple times. The dude just lives in space, I guess. It feels like Korzun and Kaleri have been with us forever. I didn’t mention them by name since there were already a lot of names flying around, but Korzun and Kaleri have been on the The Space Above Us stage since episode 153, joining Shannon Lucid during the last few weeks of her lengthy mission. Nearly 200 days later, they sailed through an uneventful entry and return to Earth.

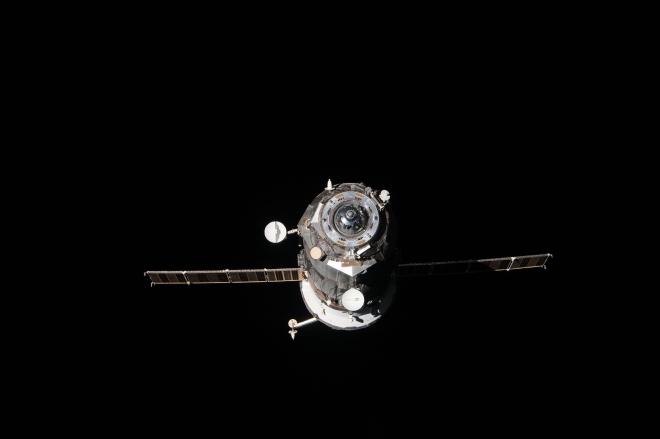

With the Kvant-1 port unoccupied, the path was now clear for the return of an unwelcome guest: Progress M-33. Almost a month ago, the crew had been glad to be rid of it. Just as a quick refresher, Progress is a cargo version of the Soyuz spacecraft. It’s basically the same thing but with the life support equipment removed, which makes it capable of carrying more stuff. Russia had been using them to keep space stations well-stocked for decades. When a Progress arrives, the crew unpacks all of the food, clothes, experiments, and other equipment, and distributes it around the station. Then before the Progress leaves, they fill it back up again with garbage that they no longer need. This could be obsolete experiments, big tanks full of waste water, literal garbage, and so on. This way rather than continuing to take up valuable room on the station, it goes out in a fiery blaze of glory somewhere in the upper atmosphere.

It sounds simple in principal but if there’s anything we’ve learned on this show it’s that nothing is as simple as it seems in space. When a Progress is sent up into orbit, an entire team of engineers and technicians carefully plays three-dimensional Tetris in order to fit as much cargo as possible. But on top of that, they also very carefully track the center of mass of the entire spacecraft and all of its contents. Without keeping a close eye on the center of mass, the Progress could end up poorly balanced, which could lead to control difficulties during ascent or while making the delicate final approach to Mir.

But now, instead of a whole team of people, we’ve just got Tsibliyev, Lazutkin, and Linenger, who don’t exactly have a lot of free time on their hands. And instead of a bunch of equipment that was supposed to fly together, it’s whatever they can figure out how to get into the spacecraft. So the task gets a lot trickier. The crew and ground would work together to try to ensure that the center of mass was correct and that things were secure. This got even trickier when the ground would change their minds on not wanting something to burn up after all, requiring the crew to unpack everything in between that item and the hatch, go get it, and then repack again.

All of that packing and repacking was never going to be perfect, but it’s not like it really needed to be completely perfect. As long as the Progress was able to back away and keep the engines pointed in more or less the right direction, it would complete its task of burning up in the atmosphere. It’s not like it had to once again complete a delicate and sensitive rendezvous and docking with Mir.. right?

This is part of the reason that the crew was less than thrilled when they learned that the Progress would, in fact, be returning to dock at the Kvant-1 port. The other part, as Linenger joked, was that the ground might ask them to rearrange the interior once again, and after a month on its own, the smell onboard the Progress was not going to be great.

OK so this begs the obvious question: why? The “why” actually brings us back to the fall of the Soviet Union. When Soviet Union failed, it broke up into a large number of nations. The biggest, of course, was Russia. But there was also Latvia, Uzbekistan, Estonia, Belarus, and so on. But critically to our story, there was the Ukraine. Ukraine was where the Soviet space program manufactured their sophisticated rendezvous and docking radar system: Kurs. Unfortunately, and apparently somewhat confusingly, for Russia.. Ukraine was now its own country. And it was not a country that was super stoked to be helping the Russians out. To make a long story short: Ukraine wanted more money for the rendezvous radars, and Russia didn’t want to, or couldn’t, pay it.

To get around this, Russian ground controllers wondered if it would be possible to forego the Kurs system entirely and just completely rely on the backup system. Right off the bat, even before I tell you anything about this backup system, you can probably tell that this isn’t a great idea. Because now instead of having a primary and a backup system, Russia would be relying on a single system and just hoping that it didn’t break.

But this idea was especially bad because the backup system was essentially just a video camera on the Progress, beaming live video to a TV on Mir, where the commander would use onboard controls to manually pilot the spacecraft in. This system really only existed for a situation like we saw when Tsibliyev and Lazutkin arrived in the first place: the spacecraft gets most of the way there, isn’t quite aligned, and needs a little manual help closing the final few meters. Instead, ground controllers would be sending Progress towards Mir and having the crew handle not only the final approach, but also the transition from far-field to near-field rendezvous. And to top this all off, when I say that the Progress sent a video feed, I mean that’s all it sent. There was no range or range-rate data, no indication of the relative velocity vector, nothing. So the Russian plan.. was to eyeball it, literally. If it worked, then gobs of money could be saved by buying fewer rendezvous radars. But if it didn’t work.. well. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

On March 4th, it was time for the test to begin. The trash-filled Progress M-33 would approach Mir, Tsibliyev would pick up the video signal, and using controls in the Base Block he would manually complete the docking. According to Linenger, despite the unorthodox request, Tsibliyev seemed confident and happy, almost looking forward to it. After all, pilots love nothing more than a little stick time. But this was going to be a tricky task. Orbital rendezvouses aren’t easy even under ideal circumstances. But today Tsibliyev would be attempting to take control of a Progress that would be arriving with only a general idea of its trajectory and velocity, and then try to brake, line up with the docking port, and execute the final docking, all with nothing more than a 2D image.

That’s because for this test, while Lazutkin would be peering through the windows of the Base Block, and Linenger would be watching from Kristall, Tsibliyev would have no window of his own. He would just be watching his TV monitor and operating the controls. He would be relying entirely on the video feed from the Progress and, if necessary, verbal reports from Lazutkin. So.. you can understand why the mood of the crew rapidly shifted when Progress arrived.. and the video feed didn’t kick in.

According to Linenger’s account, his headset went dead in Kristall, so he floated over to the Base Block to see what was going on. He spotted Lazutkin looking out the windows and imploring Tsibliyev to apply more braking. Meanwhile, Tsibliyev was frantically moving back and forth from the controls to the small window across the module, attempting to make control inputs and then observe the effect. As Linenger points out, Lazutkin was doing his best to convey the movement outside, but in this situation what is up, down, left, and right? Commander Tsibliyev spotted Linenger and told him to get in the Soyuz and prepare to abandon ship. The crew tensed for the imminent impact.. and then relaxed when it never came. Through the windows, they saw the Progress go flying past. It was a near miss, but no contact was made. For the second time in just a few weeks, Jerry Linenger had survived a near catastrophic accident on the Russian space station Mir.

When Linenger later spoke with his NASA support team they were surprised that he was so worked up over the incident. They were completely unaware of just how dangerous the situation had been, and were under the impression that there was just some minor hiccup during the attempted redocking so the attempt was canceled. Contemporaneous space reporting passed along what NASA thought to be the case: quote “The Progress M-33 cargo ship, which has been orbiting separately from Mir since Feb 6, failed to redock with Mir on Mar 4. It will be deorbited. Launch of Progress M-34 is scheduled for early April.”

The dangerous experiment had failed, but not quite catastrophically. Unfortunately, this isn’t the last time we’ll be discussing the concept, but that’s a story for another day. Progress M-33 missed, and as mentioned just now, Progress M-34 did indeed dock in April, delivering fresh supplies and equipment.

As life onboard Mir continued, the venerable space station continued to show its age. Early in March, the system dedicated to turning wastewater into breathable oxygen failed. The system, called Elektron (with a K) had a backup, but the backup was generating too much hydrogen so had to be turned back off. Until repair parts could be sent up and the system could be fixed, this left the crew with only one option: back to the candles. At least this time they didn’t have to cut off their escape route.

In the meantime, other systems struggled. An attitude control sensor failed, leaving the onboard computer blind as to their orientation, even though the control moment gyros were still working just fine. A backup system kicked in but it took several minutes, with the crew placing the station into a free drift. With nothing else controlling its orientation, Mir settled into a gravity gradient stabilized attitude. This is nice and simple but it doesn’t keep the solar panels pointed at the sun, so power was partially lost and nonessential systems had to be shut down. Linenger described the power loss, saying quote “Last night it got really, really, really dark in my room, module Spektr. Lost all power. I’ve been in dark places before, but this was unearthly dark. Darker than any dark I’ve ever seen. Dark is not even the proper word for it.”

Mir also experienced issues with some of its cooling systems. Aging coolant lines, well past their expected service life, began to leak ethylene glycol coolant into the station. This may not elicit the proper reaction until I point out that ethylene glycol has another name: antifreeze. The fluid was flammable, hazardous to inhale or get on the skin, and also filled Mir with a low level of toxic fumes. Once again donning respirators to avoid inhaling the toxic liquid, the Russian crew opened the walls of Mir and attempted to stop the leaks. But since several of the lines were all starting to leak, and some were difficult or impossible to physically reach, it was an ongoing source of irritation and frustration.

As Linenger’s stay on Mir neared its end, we finally get to a major event that was something good for a change. On April 29th, Jerry Linenger became the first American to perform an EVA outside another country’s spacecraft, wearing another country’s spacesuit.

Actually, the EVA was already noteworthy before the crew even headed outside, at least in a tongue in cheek kind of way. Progress M-34 delivered the spacesuit that Linenger would be wearing outside, and while inspecting the suit he discovered a little contraband courtesy of some folks on the ground. Up one sleeve was a bottle of cognac, and up the other was a bottle of whiskey. Linenger wasn’t partaking in any drinking while on Mir, but that’s still gotta make anyone chuckle.

On April 29th, Mir Commander Vasily Tsibliyev and Jerry Linenger donned their Russian Orlan space suits, climbed into and depressurized the airlock, and headed outside. The five hour EVA itself was pretty straightforward compared to some of the ones we’ve talked about on this show. The primary goals were to test out the new suits, install a couple of experiments on the exterior of the station, and grab a micrometeoroid experiment and some material science experiments. But if the objectives of the EVA were relatively straightforward, Linenger’s experience certainly wasn’t.

Ever since the first shuttle EVA back on STS-6, every one of NASA’s spacewalks had had the space shuttle orbiter as a home base for the EV crew. Even the earlier NASA spacewalk at Mir had been done from the shuttle, and Linda Godwin and Rich Clifford never strayed far from the big white spaceplane. For this spacewalk, Tsibliyev and Linenger would be clamoring around the exterior of the massive Mir space station, moving from module to module and reorienting themselves, with no shuttle in sight. That alone was something new for NASA, but it also meant that if something went wrong and someone became disconnected from the station, there would be no rapid rescue. So the crew had better be mindful of their two safety lines.

Another major difference was how the crew got around outside the station. We’ve become accustomed to spacewalkers being maneuvered around the shuttle payload bay with their feet firmly planted at the end of the remote manipulator system, the robot arm. This highly capable system could help transport items, could deliver crew to where they need to be, and could give them a stable working platform while they were there. The Russians had no such arm. Instead, they had Strela, Russian for Arrow.

Strela is essentially a big telescoping pole that was free to pivot around its connection to the station. The crew would manually turn a crank on the mechanism, extending the pole to the desired length, up to about 14 meters, or 50 feet. The result was sort of like the pole you see in a firefighter station, but with a bunch of fabric loops for crew members to grab onto. Linenger grabbed his payload and clipped in to the end of the arm. Then Tsibliyev turned the crank to begin extending the pole, sending him out towards another module. Suddenly finding himself far from the structure of Mir, Linenger described being struck by an intense feeling of falling as well as a sudden awareness of just how fast he was traveling. Somehow from within the confines of a spacecraft, with only a few windows to peer out, the brain just accepts the view and ignores the fact that it’s flying by at 8 kilometers per second. And as for the feeling of falling it’s actually nothing new. We’ve seen it most recently with crew members working quote-unquote “high above” the Shuttle payload bay during STS-61, the first Hubble servicing mission. But we’ve also seen it back in the Skylab days, when crew members would climb quote-unquote “up” to the Apollo Telescope Mount to swap out the film. Somehow, being a decent distance away from the primary structure, be it Skylab, Shuttle, or Mir, tricks the brain into thinking they’re up high. Combine that with the sensation of weightlessness and the now-unobstructed view of the ground speeding past and it can feel like you’re tumbling out of control at a million miles an hour. Linenger had to rely on his training and focus on the mental logic that assured him that he was safe.

And in fact, Linenger’s description of the entire spacewalk are pretty vivid. In one of the dozens of open letters that he wrote to his infant son, he discussed the experience. First, he explains that it’s impossible to truly convey what he saw and felt. He asks “What is a spacewalk like? Like a spacewalk.” The full letter is too long for me to read here, so I’ll link to it when I post the episode, but here are a few excerpts that jumped out at me.

Linenger writes, quote: “Imagine this. You are in scuba gear. Your vision is restricted by the size of your underwater mask. Your fins, wetsuit, and gloves make you clumsy and heavy. The water is frigid; in fact it is thickly frozen overhead with only one entry-exit hole drilled. Your life depends on your gear functioning properly the entire time. The farther away you venture, the farther away the escape hole in the ice, and the less you can tolerate any failure whatsoever.”

Skipping ahead, he continues: “You are not in water, but on a cliff. Crawling, slithering, gripping, reaching. You are not falling from the cliff; instead, the whole cliff is falling and you are on it. You convince yourself that it is okay for the cliff and yourself on the cliff to be falling because when you look out you see no bottom. You just fall and fall and fall.”

Skipping ahead again, “You know you are falling with it, you tell yourself surely you are falling with it because you just attached your tethers; yet it is difficult to discount the sensation that you are moving away, alone, detached.”

And finally, “In the midst of all of this, you carry out your work calmly, methodically. You snap a picture or two, and below notice the Straits of Gibraltar narrowly opening to the Mediterranean. That is how it felt, best as I can describe it.”

So yeah, like I said. Vivid. Tsibliyev and Linenger’s spacewalk was another important milestone in the growing relationship between the American and Russian space programs. And for once on this mission, it was a really positive one.

A little more than two weeks after the EVA, a familiar sight was visible out the window, and Jerry Linenger must have been glad that he had saved some film. Out the window, scooting on up the R-bar, was Space Shuttle Atlantis, back for another swap of crew and equipment on STS-84, which we’ll hear more details about on another episode. Suddenly Mir was once again a hive of activity, with a whopping ten people on the combined Shuttle-Mir spacecraft. After introducing his replacement to the facility, and saying goodbye to his Russian crewmates, Linenger soon found himself again seeing a spacecraft fading to a small bright dot on the horizon, but this time it was Mir. Before long it was time to sail through reentry, and touch down at the Kennedy Space Center. Over the last 132 days Jerry Linenger had experienced culture shock, completed valuable science, coped with questionable comms, taken beautiful photographs, survived a catastrophic fire and near-collision, and capped it all off with a history-making spacewalk. Welcome home, Jerry.

So.. again, we must ask, what are we to make of this mission. On the one hand, Jerry Linenger’s flight marked NASA’s fourth successful stint in a program that was steadily making progress in its goal of bringing NASA and Roscosmos closer together while helping to prepare for the ISS. With this mission, NASA astronauts have spent over 500 days living and working on Mir. But on the other hand, despite being a success, this mission clearly came with a number of problems. Mir’s aging systems were starting to fail more and more often, which created more opportunities for dangerous situations like the oxygen generator fire. Russia’s financial difficulties were leading to risky and reckless decisions like the no-radar rendezvous attempt. And most worrying of all, information was not flowing as it should. While Linenger got along great with his Russian crewmates and trusted them with his life, trust with the ground was nearly at a breaking point. And whether through Soviet inertia or deliberate subterfuge, the Russian space program was simply not being open and forthright with NASA.

This feels like an inflection point in the Shuttle-Mir program. Norm Thagard and Shannon Lucid experienced some hiccups, but all things considered there were no major issues with their flights. Even John Blaha’s problems were largely related to improperly calibrated expectations leading to a lot of stress. But with Jerry Linenger we have moved beyond cultural friction and into life or death peril and a dangerous lack of information sharing. Things would get better between NASA and Russia.. but first it would have to get worse.

Next time.. what better way to recover from a complex and history-making mission than with.. another complex and history-making mission? For the second time, a certain orbiting observatory is due for a tuneup. It’s time to head back to the Hubble Space Telescope!

As Astra, catch you on the next pass.