Episode 161: STS-81 - Space Deli (Linenger to Mir)

Table of Contents

On STS-81 we’ll deliver Jerry Linenger to his new orbital home, bring John Blaha back to Earth, throw some meat and cheese around in weightlessness, and try not to get lost in Mir’s darkened twist and turns.

Episode Audio #

Photos #

Post-Flight Presentation #

You can also see the mission in motion by checking out the post-flight presentation, available here:

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 161. Space Shuttle flight 81, STS-81: Space Deli

Last time, we took a quick break from press kits, mission reports, oral histories, and all the other usual sources, and heard about flying in space straight from someone who’s been there himself: astronaut Tom Jones. Jones gave us some great details about the duties of a middeck crew member during ascent, some insight into mid-90s skepticism of the Shuttle-Mir program, what Story Musgrave may have been thinking as he hung out on the flight deck during reentry, and more.

Talking to Tom Jones was a great time, and I think we’re all looking forward to reading his upcoming book Space Shuttle Voices, but for now, we once again roll the clock back and turn our attention to the first shuttle flight of 1997: STS-81.

The mission we’ll be discussing today will feel pretty familiar, since we’ll be retreading ground that just a few episodes back was exotic new territory, and heading to the Russian Space Station Mir. Our primary objective: to retrieve John Blaha, deliver Jerry Linenger, and make sure that thousands of pounds of supplies and equipment are on the correct side of the hatch when Atlantis backs away. We’ll again be using SPACEHAB in the double-module configuration, leaving plenty of room for cargo and experiments. Today’s flight doesn’t feature much in the way of drama, but don’t worry. We’ll more than make up our drama budget in the next episode.

We’ve got a shuttle full of spaceflight veterans this time, so it’s familiar faces all around. Let’s meet the crew!

Commanding the flight was Mike Baker, aka Bakes. When we last saw Baker he was commanding STS-68, the second Space Radar Laboratory mission. If that flight sounds familiar, it’s because one of the mission specialists was none other than Tom Jones, who we just spoke to last time. This is Baker’s fourth and final flight.

Joining Bakes up front was Brent Jett. We know Jett from his role as pilot on STS-72, which among other things retrieved the Japanese-made Space Flyer Unit, returning it safely to Earth. That flight lifted off almost exactly one year before today’s mission, so it’s been a busy year for Jett. This is his second of four flights.

Behind Jett on the flight deck for ascent was Mission Specialist 1, Jeff Wisoff. Like Commander Baker’s, Wisoff’s previous flight was also STS-68, the Space Radar Laboratory 2 flight. This marks his third of four missions.

Moving over to the left, seated behind and between the pilot crew we find Mission Specialist 2, John Grunsfeld. Grunsfeld last flew on STS-67, helping operate the cluster of specialized telescopes that comprised the ASTRO-2 payload. And speaking of ASTRO, if anybody is interested in a new conversation starter for your living room, at the time of this recording, some guy on the Washington DC craigslist is selling the Broad Band X-Ray Telescope from ASTRO-1. Despite it being a 32 year old relic designed to work with a spacecraft that no longer operates, the asking price is an eye-watering one hundred million dollars, which is probably more than it cost when it was actually relevant. And speaking of relevance, let’s get back on topic. STS-81 marks John Grunsfeld’s second of five flights.

Moving downstairs to the middeck we find Mission Specialist 3, Marsha Ivins. Ivins is another frequent flyer, most recently serving on the crew of STS-62, the US Microgravity Payload 2 mission. This marks her fourth of five flights.

And last but not least, Mission Specialist 4, Jerry Linenger. When we last saw Linenger, it was on STS-64, which among other things demonstrated the new “SAFER” apparatus in a rare untethered EVA. Once Atlantis arrives at Mir, he’ll swap places with John Blaha, who will then become the new Mission Specialist 4. This is Linenger’s second of two flights.

The flight was pushed a bit down the calendar due to the flights before it being delayed by SRB problems. As always, delays create more delays. But on launch day itself, January 12th 1997, there were no delays in sight. The crew suited up around midnight, climbed aboard the astrovan for the short drive to the pad, and strapped into the seats on Space Shuttle Atlantis to await liftoff. The countdown proceeded smoothly with no unscheduled holds and at 4:27:23 AM, Atlantis rose from the pad to begin its nominal ascent. At that moment, Mir was flying high above the ocean, somewhere near the Galapagos islands. The orbiter itself experienced no issues during the ride uphill, but the right-hand SRB decided to throw the Thiokol folks a curve-ball, getting the risers for one of the parachutes tangled with a vent line, and causing a harder than usual splashdown. The SRB was fine, but I’m sure it kept folks busy until they could be positive that it wasn’t a problem.

In an interview, Mission Specialist Jeff Wisoff talked a bit about what it feels like in the shuttle right at the moment of main engine cutoff, or MECO. As the orbiter expends propellant and gets lighter, the G-forces mount, eventually requiring the engines to throttle back in order to remain at a more comfortable 3 times the normal force of gravity. But “comfortable” is a relative term here. Wisoff described the sensation as feeling like a bear is sitting on your chest. But suddenly, MECO. The bear is gone, and the ends of your seat belts drift up into view, and you know you’ve arrived in orbit. Just a few seconds later there is a loud clang as the external tank is separated. Wisoff said the actual sound of the empty metallic clang is much louder than in the simulators, and often catches rookies off guard. And then right after that, the cannon-like primary RCS thrusters kick in with a series of loud booms as they move the orbiter away. To me it seems akin to a little fireworks show to celebrate a successful orbital insertion.

Among the usual tasks of opening the payload bay doors, activating a handful of secondary experiments, and executing the rendezvous maneuvers, the early days of the mission were occupied by assembling and testing a new treadmill system down in SPACEHAB. Residents of Mir were all too familiar with just how much influence someone jogging on the treadmill could have over the entire station. In fact, Shannon Lucid discovered that her running pace just happened to be close to a harmonic of the station, resulting in vibrations growing larger and larger until a frantic Russian crewmate urged her to stop before shaking the entire station apart. The Treadmill Isolation and Stabilization System, or TVIS, aimed to solve this problem.

Using some clever engineering, the vibrations from the crew’s pounding feet would be damped out and barely make a difference on the surrounding structure. Unfortunately, some unclever engineering lead to a series of frustrating problems. First, somehow, TVIS did not match with the orbiter’s power cables. This one is kind of baffling to me since I would imagine that this payload was being supported by a mountain of interface control documents and engineering specs. But here we are. No matter though, the crew performed an in-flight maintenance procedure to install some jumper wires and get the system going.

Once TVIS was running, the crew could get running! The system worked great, doing exactly what it said on the box. Astronauts were able to get in a good workout without shaking their spacecraft to pieces. The only problem was that through a series of mishaps, the engineering data supporting this evaluation was not properly recorded. I’m not sure on the exact sequence of events here, but at various points the memory card had a read-only switch enabled, a configuration file had the wrong values and wouldn’t write to the card in the first place, and the Payload General Support Computer aka PGSC aka “laptop” had malfunctioned. The crew would actually have to reassemble TVIS and do it all over again after departing Mir. Oh well, at least they got a decent workout in.

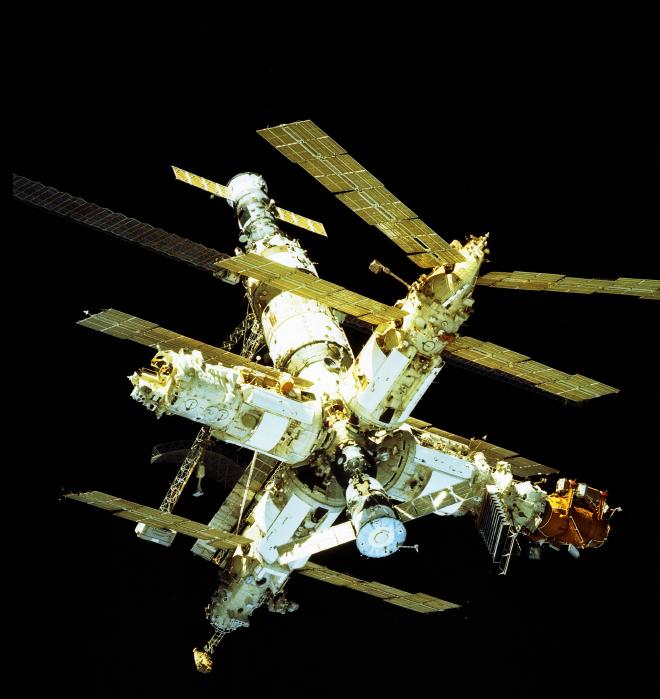

Flight day three was the big day, with Mir becoming visible on the horizon as what appeared to be a very bright star. Jerry Linenger described in his book “Off The Planet” how as Atlantis drew closer, that bright star became better defined, eventually resembling a quote “Tinker-Toy-like monstrosity floating in space.” I should mention that I found several passages of Linenger’s book to be helpful when looking for some extra details, which is why it gets mentioned here a lot, but I’ve really only just started it, so I’ll hold off on a proper book review until later. Anyway, Linenger went on to describe Mir as looking like six school buses hooked together, with four of them having crashed into each other from four different directions. Well, school bus crash site or not, that’s your home for the next few months, Jerry.

As always, the rendezvous was a team effort. Marsha Ivins operated the laser range-finder out the window, providing the shuttle computers with critical range and range-rate data. Jeff Wisoff kept an eye on various systems, especially the docking mechanism. Brent Jett and John Grunsfeld were sitting in the Commander and Pilot’s seats, respectively, running the checklists and keeping the computer up to date. Jerry Linenger operated the VHF radio and kept the Russian crew up to date on what was happening. And Commander Baker was situated at the aft of the flight deck, manually controlling Atlantis for the final approach. Pilot Brent Jett said that the rendezvous was too busy for him to really get a good look at the station as they approached. But he did zip to the back of the flight deck a few times to peer out the overhead windows at the orbital outpost.

2 days, 18 hours, 27 minutes, and 28 seconds into the mission, Atlantis made contact with the Docking Module. The mechanisms on both sides latched into place and the oscillations induced by the snail-paced collision were damped out. I had to laugh when I watched the post-flight presentation and saw video footage from the center-line camera. Why? Well, remember how I told you that on a previous mission the crew used some Kapton tape to reattach the black target indicator? Well there it was, right on the video. They did a good job though! It looked great!

Just over two hours later, the requisite pressure equalization procedures and systems checks had been performed, and the crews opened the hatch. As Linenger described it, they were greeted by an ecstatic John Blaha who let out an uninhibited laugh and called out “Welcome! Welcome to space station Mir!” Soon after that there was quote-unquote “bedlam” as the new-to-space shuttle crew clumsily navigated through the hatch.

The transition from the shuttle environment to Mir made an impact on several crew members. Mission Specialist John Grunsfeld compared exploring the station to exploring a cave. Mission Specialist and new long duration resident Jerry Linenger paints a picture of a dim station that smells like his grandparents’ basement. Pilot Brent Jett described how soon after arriving, Flight Engineer Aleksandr Kaleri noticed Jett struggling to find his way through Kristall and pointed out a line they had installed to aid in navigation and movement. The reason that Jett was having trouble was that Kristall, one time a cutting edge spaceborne research facility, had, as he tells it, essentially been turned into Mir’s attic. Other than a narrow passage in the middle it was completely jam-packed with stuff. But more on that later, because as the crew continued on through the node and then into the base block, they found an environment that was a little more like the space station they had expected.

Shortly after arriving, a press conference had been scheduled, so the crew began to assemble. But it was called off when Mir’s master alarm sounded. Linenger thought that Korzun seemed more embarrassed than distressed as he explained that it was caused by low electricity levels and began shutting down some lights. Linenger glanced at Blaha who returned a knowing look. Not the most auspicious start, but no harm done. The crew continued their work.

For the second time, Atlantis carried the double SPACEHAB module in its payload bay, providing ample space for equipment, supplies, and experiments. Of course, there was the mandatory reentry suit and seat liner for Linenger, in case an emergency return to home on the Soyuz was required. But there was also around 500 kilograms of US research equipment, 1000 kilograms of Russian supplies, 120 kilograms of some miscellaneous gear, and 635 kilograms of water spread across 16 bags. Coming back on the shuttle was over a metric ton of equipment that was no longer needed, along with scientific samples such as the wheat that had been planted by Shannon Lucid and harvested by John Blaha. The wheat samples represented the first plants that had gone through an entire life cycle in space, and scientists were eager to get their hands on them.

With so much stuff crossing through the docking module, it was important to have one person who took overall responsibility for tracking everything, and for today’s flight the load master was Marsha Ivins, who is reported to have ruled with an iron fist. She knew exactly where everything on the shuttle was and exactly where it needed to be. Her careful organization and attention to detail was no match for the general chaos of Mir, however. Linenger describes encountering Ivins as she was attempting to make her way to the Progress resupply vehicle docked to the Kvant 1 module, only to be stymied by floating clutter in the astrophysics module.

Getting to the Progress under normal conditions would already be a somewhat daunting task. Just as a hypothetical, let’s imagine that Ivins started out this quest by first enjoying the view out the flight deck. She would first drift down to the middeck, then begin to float down the tunnel to SPACEHAB. But before getting all the way there, turn not left, not right, but up and into the docking module, continuing on through the equipment floating around Kristall. From there she would end up in the node, where six different modules come together. She’d have to turn 90 degrees and enter the base block, the command center of the station. Drift all the way through and we finally arrive at Kvant 1.

Once there, Ivins got lost among a sea of old equipment, storage containers, and plastic bags full of stinky garbage. She asked Linenger if this was the right way to the Progress, which was theoretically in the back of the module. I had to laugh because while Brent Jett compared Kristall to Mir’s attic, Linenger went on to describe Kvant 1 like this, quote: “Generally the space station resembled an old attic belonging to an eccentric recluse, a perpetual saver of all things, a person who believed adamantly that ‘You never know when it might come in handy.’ and who, therefore, has amassed a lifetime of ancient and useless stuff.” So.. hoarders. We’ve got space hoarders.

Toooo be fair to Korzun and Kaleri, and as Linenger rightly points out, this wasn’t all their garbage. It had accreted over the course of more than a decade of flying in space. During that time, dozens of crew members across more than 20 missions came and went, each with their own batch of essential supplies and unique equipment. And unless you wanted to destroy something by sending it back in a Progress with limited space, the only option was to hang onto it. The Soyuz simply did not have much down-mass capability. So the list of stuff grew and grew and grew.

Amid all the sifting through clutter and transferring equipment, one very important task was underway. John Blaha had spent the last few months with a sense of frustration that he was inadequately prepared for what life onboard Mir was truly like. Seeking to rectify this, he had carved time out of the schedule to walk through things with Linenger, who would soon be replacing him. Blaha explained how to use the treadmill, how to use the toilet, where things actually were instead of where the ground thought they were, and even how to stay clean. Blaha demonstrated how even 2 or 3 thimblefuls of water could be sufficient to clean up after a workout with a little care and planning. When we discuss Linenger’s extended mission in detail, we will learn about some pretty alarming and dangerous situations. It’s entirely possible that Blaha going the extra mile here made a real difference in how events played out. But that’s a story for later.

Something that was not nearly as essential, but a lot funnier, played out a few days after Atlantis arrived at Mir. Listeners of a certain age may be familiar with the National Public Radio program “Car Talk” starring Tom and Ray Magliozzi aka Click and Clack, the Tappet Brothers. For those who are not familiar, Car Talk was an hour long show that played every week for 35 years. People would call in to ask for help with unusual car problems, and Tom and Ray would lend them their expertise, in-between cracking jokes and slipping into bouts of cackling laughter. Well, it turns out that when Mission Specialist John Grunsfeld was studying at MIT, he occasionally brought his car to the garage operated by two other MIT alums: Click and Clack. After a pre-flight call to the show’s producers to arrange things, the stage was set.

So it was that on an episode of Car Talk, “John from Houston” called in to talk to the Tappet Brothers. He said that he occasionally drove a government vehicle that was quote “one of those Rockwell things”. He went on to say that it starts great and accelerates really really well, but runs incredibly rough for the first two minutes before experiencing a jolt and then smoothing out. But then only six and a half minutes after that the engine dies entirely. Even weirder, he had encountered this on two different vehicles of the same type but with different serial numbers. Of course, Grunsfeld neglected to mention that those serial numbers were OV-105 and OV-104.

The hosts were momentarily a bit perplexed, but despite intentionally coming off as doofuses, they were actually pretty clever. One of them soon latched on to the unique quality of the sound of the phone call, which sounded awfully similar to Tom Hanks in the recently released film Apollo 13, saying “Houston, we have a problem.” Finally, they asked the caller where he was calling from. Grunsfeld said he needed a second to look, before replying “about 200 miles north of Hawaii”

At this point the jig was up, and the duo had fun asking some more questions about the shuttle and the mission, while also reminiscing about Grunsfeld’s old beater of a car. Before signing off, they reminded Grunsfeld that he still owed them five bucks from the last time he rented a repair bay!

I’m going to link to the audio of that exchange in the announcement tweet for this episode, but you can find it pretty easily by searching for “Car Talk STS-81”. I’ve also reached out to the folks running Car Talk these days asking if I could play the clip as a supplemental, so if we get lucky it’ll just be on the podcast feed.

Life aboard Atlantis and Mir continued on largely uneventfully. Linenger moved in, Blaha moved out, everyone moved equipment around, and there were few significant anomalies on the orbiter. But there was one minor glitch I wanted to bring up for the sake of one listener in particular. One instrument studying the shared atmosphere of the shuttle and station was the Volatile Organic Analyzer. It was powered up and left to bake out, basically waiting for any compounds in the instrument from before the flight to outgas before it was ready to start taking measurements. Unfortunately, shortly after that the current in the instrument dropped and it shut down. The crew and ground couldn’t figure out what was going on with it but suspected that the 3 amp fuse had blown. The fuse was not accessible by the crew, so there wasn’t much to do but shrug leave the system shut down until another flight. The official mission report didn’t expand on the true cause of the failure, but fuses always make a convenient scapegoat. Right, Jack?

Of course, like all the Shuttle-Mir missions, the two crews found ways to have some fun together. There was the usual exchange of gifts, with the shuttle crew bearing some pragmatic gifts such as some new flashlights and high quality can openers. They also brought a less pragmatic, but beautiful gift: a stained glass Mir, complete with stained glass Atlantis. Though in a sort of funny twist, the shuttle crew also brought it back home with them since, again, the Soyuz isn’t so great for bringing stuff back to Earth.

The Russians put their new can opener to good use, breaking out some of their better supplies, along with some fresh treats from home. In addition to some of the more coveted food items from the standard supplies, Korzun and Kaleri cut pieces of highly prized cheese and salami, tossing them across the weightless cabin to hungry astronauts. Jeff Wisoff said it was like being in a space deli and was one of the best meals he’d ever had in space.

And on top of all that, while docked, Jerry Linenger celebrated his 42nd birthday. The combined crews enjoyed some birthday cake and some favorites from the shuttle’s pantry including dehydrated shrimp cocktail. And what would a birthday party be without dehydrated shrimp cocktail?

After five days of docked operations, it was time for the crew of STS-81 to say goodbye. Though somewhat hilariously, in the post-flight presentation Blaha felt the need to point out that the video footage of the crews exchanging goodbyes was a quote “fake goodbye” staged for the camera. Thanks John.

With Blaha and Linenger on the correct sides of the hatch, the docking sequence was played out in reverse. Though with all the jokes about how eager Blaha was to be going home, I don’t think there was any doubt as to which side of the hatch he’d be on. With the flip of a switch by Jeff Wisoff, the mechanism unlatched and springs pushed the orbiter away before Commander Baker followed it up with some low-Z thruster pulses. After two trips around Mir for the usual flyaround and photography, Atlantis once more fired its thrusters and flew away.

The mission wasn’t quite over yet though. Along with tending to a few experiments in the Biorack module in SPACEHAB, there were a few other odds and ends to keep the crew busy before heading home. As I mentioned earlier, they had to once more assemble the TVIS treadmill for another test run. They also kept an eye on KidSat, which was flying again. This is that digital camera that students on the ground were able to operate in order to take photos of the earth. The goal had been to take at least 287 pictures, but they ended up almost doubling that weirdly specific number, ending up with 525 photos shot through the orbiter’s windows.

The crew also tested out a new medical restraint system designed to help a sick or injured crew member. In only 56 seconds, a single crew member was able to secure another in the new system. Thankfully such a system was never required, but better safe than sorry.

And of course, with much of the SPACEHAB now empty, the crew enjoyed spinning and tumbling around, hamming it up for the camera. Marsha Ivins even grabbed the camera to provide a first-person view of her weightless gyrations.

When landing day arrived, the first attempt at reentry was waived off due to unacceptable conditions at the Kennedy Space Center, but the weather cleared up in time for the second. After an uneventful reentry, Space Shuttle Atlantis landed at the Kennedy Space Center. The flight lasted 10 days, 4 hours, 55 minutes, and 23 seconds. But for John Blaha, it marked the end of over 161 days in space spread across five missions, making him the most experienced male astronaut, second in the corps only to Shannon Lucid. Welcome home, John. I hope to see you again at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex someday.

It may have occurred to you that this flight seemed a little light on science, and that’s because it was. That’s not to discount the secondary payloads that flew on Atlantis, and of course this mission enabled long duration science to be done on Mir. But the fact remains that this mission essentially used a multi-billion dollar vehicle as a moving van. I actually happen to think that this a perfectly fine use for that vehicle (it was, after all, the original idea) but I wanted to point it out because before I learned more about the Shuttle-Mir program it wasn’t immediately apparent that a trade-off was being made here.

There was no way of knowing the total number at the time, but NASA was trading over 8% of all shuttle flights to support the Shuttle-Mir program. In exchange we got to fly seven Americans on long duration spaceflights for the first time since Skylab, and we got to do some experiments that simply couldn’t be accomplished on the brief durations available on the shuttle. We also got a partner for building a future in space together, as well as a sort of test run for how that relationship would work. One could also argue that strengthening that relationship in space would help to ease the tensions that would inevitably come and go in other parts of the complex relationship between the United States and Russia. It kept them talking and working together. And talking, even if (especially if) one partner disagrees with the other, has significant value all its own.

All that is a long winded way of saying that everything in space is a trade-off. So it’s important to be aware of what it is you’re trading, even if you’re satisfied with the outcome.

Next time.. Jerry Linenger is going to want to double check his Soyuz seat liner, because his stay on Mir is going to be a little more eventful than he had planned.

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass.