Episode 179: Phase One Done (Shuttle-Mir Retrospective)

Table of Contents

With the end of the Shuttle-Mir program upon us, we take a quick look back at how it started, what happened during it, and what the ultimate fate of Mir was. I hope you like tacos.

Episode Audio #

Photos #

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 179, Shuttle-Mir Retrospective: Phase One Done

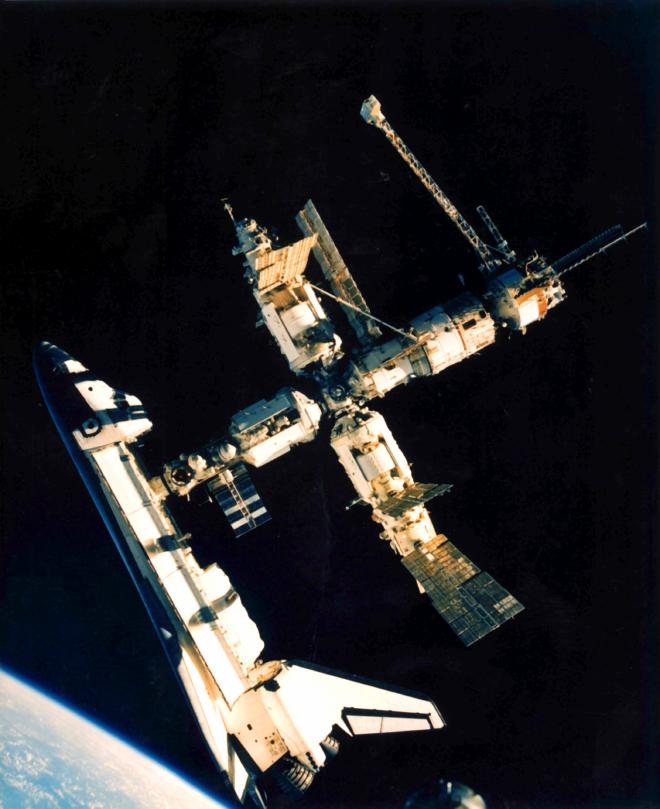

Last time, we rode along on the ninth and final Space Shuttle mission to dock with the Russian space station Mir. While there, we transferred one last batch of supplies for our Russian partners, packed up the American equipment and science samples, and welcomed astronaut Andy Thomas back to the shuttle for his ride home. With the successful entry and landing of Space Shuttle Discovery, the Shuttle-Mir program was over. Setting aside the planning and just looking at the missions, the program spanned nearly five years, with 44 Americans boarding the station, including seven who served on long duration flights. It’s pretty remarkable when you consider the whole reason that the space race got kicked off in the first place.

The program also took place across just over two years of The Space Above Us and, including this one, a kind of surprising 21 episodes. Just looking at the long duration mission coverage it comes out to over five and a half hours, which is pretty hilarious when you consider that my original plan was to just make a single episode to cover all seven flights.

So with all of that so spread out, I thought it might be helpful to take a quick look back and just sort of remind ourselves what happened. And also, to be honest, with me still sort of in recovery mode it’s a nice opportunity to write a somewhat easier episode, leaving some of the nitty gritty details to the previous episodes and to some recommended reading I’ll mention at the end.

With all that out of the way, let’s take a quick look back at Phase One, the program we know and love as Shuttle-Mir.

Deciding when a historical event started can sometimes be tricky, but I like to think of Shuttle-Mir as really starting in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union. 34 years after the Soviets scared the heck out of the American public with a small harmless satellite named Sputnik, after decades of rivalry that brought humanity to the verge of nuclear annihilation, America’s nightmare boogeyman A-number-one was gone. Except.. not really. The real world isn’t a video game. The Russian armed forces were still there, as were all the scientists, engineers, and technicians that supported them during the high tech escalation of the Cold War. Russia was still an adversary to be reckoned with, but now it was more disorganized, less predictable, and less able to pay the bills. There was a concern that the skilled men and women who had designed and built the Russian space program might be tempted to sell out to the highest bidder and go make rockets and missiles for other countries that the United States considered to be less than friendly.

So out of a desire to keep rocket scientists busy and to bring the US and Russia closer together, a partnership in space was proposed by American president George H. W. Bush and Russian president Boris Yeltsin.

What started out as a small plan to fly an astronaut on Mir and a cosmonaut on the Shuttle soon sprawled into not only the seven long duration missions that we’re now familiar with, but the International Space Station: NASA’s human spaceflight destination for at least the next two decades. Indeed, the proper name for Shuttle-Mir is “Phase One”, the first phase of the ISS project, with the ISS being Phase Two.

Since the very existence of the Space Shuttle played a not insignificant role in the ultimate downfall of the Soviet Union, it’s interesting to think of the historical ripples and echoes caused by the program. Envisioned in the 1960s, designed in the 1970s, flown in the 1980s, and then used in the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s to build and supply the International Space Station, which itself could maybe even operate into the 2030s. But I seem to have wandered off topic a bit. Let’s rein it back in and revisit the first Shuttle-Mir mission.

It’s sort of easy to forget, but the first flight of the program was actually STS-60 in February of 1994, over a year before Norm Thagard climbed aboard a Soyuz. The flight saw the inclusion of Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev, in what I look at as a sort of cultural integration test. The flight itself didn’t really have anything to do with Mir, but it was a great opportunity to host a couple of cosmonauts in the United States and teach them the way that NASA approaches spaceflight. Krikalev would later fly on the shuttle twice more, so clearly there were no issues with crew integration. STS-60 was also only the second flight of SPACEHAB, the commercialized version of Spacelab which would be used to transport large amounts of cargo to and from Mir in the years to come.

13 months later in March of 1995, Norm Thagard became the first American to launch into orbit on a Russian rocket. His experience training for the flight should probably have set off more alarm bells in NASA management than it apparently did. Thagard wanted to be treated just like the cosmonauts, which is mostly what he got. But that also meant that he dove into a compressed training schedule with very little language training and barely any NASA support while in Russia. Once on orbit, he found that he had little to do at first. Much of his work was supposed to take place on the Spektr module, which wouldn’t launch until most of Thagard’s mission was already over. He also found that he was being treated less as an equal member of the crew, and more like the Russian equivalent of a Payload Specialist. He was a welcome guest, but a guest nonetheless.

In the end, Thagard’s 115 day flight would be a success and an excellent reintroduction to long duration spaceflight for NASA. But an opportunity to recognize and stop early problems passed by unrealized. Difficulties with Russian language training, support of astronauts in Russia, and lack of sufficient communication while on orbit would become ongoing issues for much of the program.

That said, our next long duration flier seems to have soared through her mission without any significant problems. A year after Norm Thagard rode a Soyuz to orbit, Shannon Lucid arrived at Mir aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis. While she too struggled with the Russian language, Lucid and her crewmates soon learned that they were still able to communicate, even if it required resorting to some Russian-ish words in what they came to call their shared “Cosmic Language”. Like Thagard, Lucid’s work was stalled due to a delayed Mir module, in this case Priroda, but the delay was less severe so it had less of an impact. In fact, Lucid’s flight may have been the smoothest and most trouble-free of all seven long duration missions. Even with an SRB-related problem causing a delay for her ride home pushing Lucid’s mission to 188 days, easily the longest of the Shuttle-Mir missions, Lucid seemed unperturbed. Providing, of course, that she had enough reading material and Jell-O.

At the end of her lengthy stint, Shannon Lucid passed the proverbial baton over to her old Shuttle commander John Blaha, in NASA’s first ever on-orbit handover. Unfortunately for Blaha, he would be the one to suffer from that lack of experience. No special planning had gone into the brief handover period and after a few days of whirlwind activity Blaha found himself on the Mir side of the hatch, watching his predecessor, with her head full of useful knowledge, flying away. Blaha struggled to adapt to the slower but sustained pace of a long duration mission, more accustomed to the all-out round the clock effort characteristic of short Shuttle flights. This struggle to adapt, combined with limited communications and lack of understanding by Blaha’s ground support team, resulted in a frustrated and likely depressed astronaut. Unfortunately, the lessons learned during Skylab, more than 20 years earlier seem to have been forgotten. The ground simply forgot what it’s like to actually live in space for day after day, week after week, month after month. The driven and mission-oriented Blaha found himself fraying as he attempted to work an impossible schedule, confused why the ground was setting him up for failure. At the same time, while he doesn’t seem to have had any problems with his Russian crewmates, the warm sense of camaraderie that Lucid had enjoyed seemed to have been replaced by the American and the Russians mostly tending to their own business.

Despite the catastrophes that would come, I tend to think of Blaha’s stint on Mir as having the most unpleasant crew experience. Astronauts train every day to handle life-threatening emergencies. Somehow I doubt that they’re trained to handle long sustained periods of frustration and homesickness. Not to be defeated, Blaha took his bad experience and used it to motivate him to help improve the process for those who followed him. He greatly increased the emphasis on the handover and made it clear to ground support teams what the needs of the on-orbit crew members were. That said, I’m sure that Blaha was delighted to see the end of his 128 day mission.

Replacing John Blaha was our next long term resident, Jerry Linenger. Linenger benefited from Blaha’s bleak experience, with Blaha carving out additional time to show Linenger around and explain to him how life really worked on the station. Of course, we probably best remember Linenger’s mission for what happened about a month and a half into the flight: when jets of flame and billowing smoke began to spew from the Kvant-1 module. There’s never a good time to have an uncontrolled fire in space, but the timing of this fire was especially bad, coming during the multi-week handover between Russian crews, resulting in six people being on the station. Worse, the fire cut off the path to one of the two Soyuz spacecraft, which meant that a complete evacuation was not an option for the expanded crew. For fourteen harrowing minutes, the crew exhausted fire extinguisher after fire extinguisher, before the flames finally died down. And there seems to be some doubt that they even made a difference in the end. The fire may have simply run out of fuel.

The Kvant-1 fire was a stark reminder of just how quickly disasters can unfold in space, and it placed a spotlight on the Russian approach to safety. One minute the six person crew were enjoying a pleasant meal together. 14 minutes later they were blinking through their emergency respirators at the damage done by the raging fire, trying to figure out what the heck just happened and what to do next. But something that had the potential to be the most damaging of all was how Russia responded to the accident. The Russian crew tried to keep the full extent of the accident from the ground, and the Russian ground controllers in turn tried to keep the full extent of the accident from NASA. This was not how partnerships were supposed to work.

But Linenger’s 132 day mission was not all doom and gloom. He got along well with his crewmates, took thousands of stunning photos, and became the first American to perform an EVA in a Russian spacesuit. Even among the damage and distrust resulting from the fire, the two countries were still making progress on becoming partners in space.

After the nearly lethal fire of Linenger’s mission, I’m sure our next long term resident was just hoping for a nice and straightforward flight. Unfortunately for Mike Foale, this wish was not granted. Foale was initially a little wary of this mission, but went into it with a good attitude and a good work ethic. His diligent efforts to learn Russian before the flight and his willingness to do time consuming and boring, but necessary, work drew the respect of his Russian crewmates. And that respect would be critical a little more than a month later when a multi-ton spacecraft named Progress M-34 crashed into the space station. What followed was a nerve-wracking rush to save the station, and the crew. Even when the immediate crisis was over, the crew found themselves in a darkened and slowly tumbling spacecraft, completely on their own. Foale’s quick thinking, combined with the Russian crew’s knowledge of the station, allowed the trio to recover attitude control and, incredibly, get back to something approaching normality.

Mir would forever be diminished by the Progress M-34 collision, with its Spektr module suffering a punctured hull that defied repair. But I actually view this incident as a key moment in the United States and Russia partnership in space. Even more than the fire, which was more focused on short term survival, I think the slow recovery of the station proved to both sides that they could count on the other to stick it out even when things got difficult. By the time Space Shuttle Atlantis arrived to pick Foale up, life on Mir was almost completely back to normal; an incredible achievement. Combine that with another successful joint EVA and I actually think NASA-5 is a hidden gem of a mission. Obviously no telling of this mission would be complete without talking about the collision, but I think the recovery from the collision is the real story and is worthy of praise.

When Foale returned home after 144 days, the original plan was for him to be replaced by Wendy Lawrence. But the Progress collision solidified a decision that all crew members must be able to perform an EVA, and Wendy Lawrence was simply too short to effectively wear a Russian space suit. So instead, when Lawrence arrived on Mir she applied her skills and knowledge towards maximizing the chances of a successful mission for her backup: Dave Wolf.

Wolf’s stint on Mir was practically a snooze when compared to the previous two missions. Yes, Wolf still had to deal with the realities of living in a station that was well past what its designers had intended, and there still were computer failures and attitude excursions, but there were no catastrophes or near-death experiences. Well, almost. There were some tense moments when the outer airlock door failed to seal after a spacewalk, and Wolf and his commander had to disconnect from their life support systems and make their way into the smaller inner airlock before their visors fogged over.. but who’s counting.

Yes, Mir was back enough on track that Wolf was able to largely focus on the science experiments that were ostensibly the whole reason he was up there. This must have been especially fun for Wolf since before he became an astronaut he had actually been the lead behind one of the experiments that he was now performing himself on Mir. His 126 day mission passed with no major incidents and he was soon welcoming his replacement: Andy Thomas.

Upon arrival, Thomas hit a minor snag in the form of an ill-fitting Sokol suit, which would have been used in case of an emergency deorbit on the Soyuz. But really, it’s notable that that was one of the most significant problems he encountered during his 132 day mission. Yes, there was another fire, but it was far smaller and mostly self-contained. And it’s true that the attitude control computer still liked to remind everyone of the chaos it could wreak whenever it felt like it. But overall, Thomas had a nice by the books mission. In between routine maintenance of the station and his own body, wrapping up the last of the science experiments, and supporting numerous Russian EVAs from inside the station, Thomas even found some time to enjoy some video games in space, a first for an American. When STS-91 came to retrieve Thomas, it brought no replacement crew member, and that was it for the NASA presence on Mir.

To further summarize that summary, I think I can capture the seven missions with seven words: Reintroduction, Harmony, Depression, Fire, Collision, Recovery, Routine. It’s good that they were able to end on a higher note.

So what did we give and what did we get? Not counting STS-60, NASA fully or mostly dedicated ten shuttle missions to Shuttle-Mir. No one knew this at the time, but that works out to about seven-and-a-half percent of all missions of the entire Space Shuttle Program. That’s ten more missions that could have flown a Spacelab full of science experiments or deployed a satellite or tried some funky new technology like the Wake Shield Facility or the Tethered Satellite System. NASA also helped finance the completion and launch of the Spektr and Priroda modules. I didn’t dig up the numbers on how much, exactly, that cost us, but I think it’s safe to assume that new space station modules ain’t cheap. I think it might even be possible to say that the program cost NASA some political capital, as it defended itself against a Congress that was reasonably alarmed by reports of fires and collisions on Mir.

That’s a lot to give, but in return, we got a lot back. We got our first taste of long duration flight in over 20 years, allowing NASA to flex some muscles that it had long since forgotten how to use. When we look back at Norm Thagard’s car breaking down in Death Valley on his way to get some basic Russian language training and contrast it to Andy Thomas’ well-trodden road to orbit, it becomes clear that in only seven missions, NASA had made a lot of progress in re-learning the art of preparing for and operating long duration spaceflights. There was still some work to go before getting to the routine of the ISS, but the support network was already much stronger.

We got dozens and dozens of experiments, investigations, and tech demos that could only have been done with the long spans of time in weightlessness afforded by a space station. We got nearly 1000 days of crew time on orbit. And we kept Russian aerospace experts from looking elsewhere to offer their services, while also cementing a new friendship and partnership in space with our old enemies.

And that partnership extends to this day.. for the most part. Obviously, as I write this in June of 2023, things have been a little rockier on the whole “partnership with Russia” front. I have avoided the topic since I don’t like to refer to contemporaneous events too much, but yeah. Russia has been waging a devastating war against Ukraine for over a year now. It’s not good.

But I think that the ongoing conflict just goes to show how strong a bond spaceflight can create between nations. Despite the war, despite the sanctions and the boycotts and denunciations, NASA and Roscosmos continue to fly the ISS together day in and day out. Americans still fly on Soyuz and Russians still fly on Dragon. At least for now.

So, with all of that said, what are we to make of the Shuttle-Mir program? I think there are actually some parallels to Apollo. I think someone who was not a fan of either program could reasonably say that both were very risky and very expensive for not much of a concrete return. And honestly, I can’t really argue with that. But just like Apollo, I think Shuttle-Mir was worth it for the intangibles. It changed the trajectory of spaceflight history, and set the stage for the next 20-30 years of space. Again, I’m sure there are some people questioning how valuable the last few decades of spaceflight on the ISS have been, but one thing’s certain: whether you like the ISS or not, there can be no doubt that it’s better thanks to Shuttle-Mir. Everything NASA learned across those seven missions would have been learned anyway, but this time with the added challenge of building a space station thrown into the mix.

And on a selfish note, I think it’s also worth noting that we got a lot of really great stories out of the program. Some of my favorite spaceflight moments happened on Mir, and it’s been a blast relaying them to all of you.

But I suppose we should loop back and tell the end of Mir’s story. NASA’s last mission to Mir actually wasn’t too far off from the end of the station itself. STS-91 departed the station on June 8th, 1998. Onboard was Andy Thomas, who had served as a member of Mir mission EO-25. A little more than a year later, on August 28th 1999, the crew of EO-27 departed Mir, with no replacement crew on board. After more than 12 years of continuous human presence, the Russian space station was left on its own. Of course, the ground was still keeping on eye on things, but with no crew onboard performing hours of daily maintenance and repairs, it was only a matter of time until the station would hit an unrecoverable problem and that would be it.

Except, now we have to talk about reality TV. What? Yeah, I’ll explain. Russia was essentially done with Mir and were starting to turn their full attention to the nascent ISS, the first part of which had already launched almost a year earlier. But surprise, a company called MirCorp essentially wanted to buy the station, or at least pay to have to fixed up, lease it, and try to make it into a space tourism destination. One potential such space tourist would have been the winner of a planned reality TV show called Destination Mir. This would have been a show in the same style as Survivor, starting off with a big group of contestants and then every week someone would be kicked out by actual Russian officials. In the meantime, the show would focus on training and presumably dumb little games and confessionals and manufactured drama and such. It was, after all, a reality TV show.

MirCorp gave the Russian government a whole boatload of cash to keep flying the station and they even funded one final flight to the station: Mir EO-28. The mission was commanded by Sergey Zalyotin on his rookie mission. We’ll see him again on the ISS so I won’t do a proper biography today. Joining him as flight engineer was Shannon Lucid’s old buddy Aleksandr Kaleri. 222 days after Mir was left to fend for itself, the new crew arrived and began to get to work on fixing the station, including fixing a small air leak. In fact, the leak had been bad enough that after docking, the crew had to pump additional air in before opening the hatch.

The station was still running, but things were getting pretty rough. The available onboard power had diminished to the point that the Priroda module could no longer be used, at least in part due to an external cable on Kvant-1 that had somehow burned through from a short circuit. After 10 weeks of work, on June 15th 2000, the duo left. No one would ever see Mir up close again. Additional funding to repair the station fell through, a second repair mission was canceled, and that was it for Mir.

In early 2001, a Progress cargo spacecraft was launched to dock with the station. This was one of the first of the new M1 Progress variant, which had additional propellant capability. This was good, because this Progress would be used to safely deorbit the station, so the more propellant the better. A safe deorbit was extremely important, since allowing Mir to come down in a populated area could have been catastrophic. With that in mind, a backup crew of Gennadi Padalka (who had flown the mission after Andy Thomas’s) and Nikolai Budarin (who had flown with Thomas) was ready to launch and fix any problems if needed.

Not wanting to squander a good news story, Taco Bell took advantage of all the attention being paid to the station’s demise and set up a 40 foot by 40 foot floating square in the South Pacific Ocean. Painted on the square was a giant bulls eye with the Taco Bell logo at the center and the words “FREE TACO HERE”. The fast food company had promised a free Taco to everyone in America if the core of Mir hit the target. It was a pretty good bet considering that the target was placed just off the coast of Australia and Mir was actually being aimed several hundred miles out to sea, but just in case, they took out an insurance policy. You never know. And yes, if this entire episode was dedicated to Mir’s demise, the title 100% would have been “FREE TACO HERE”.

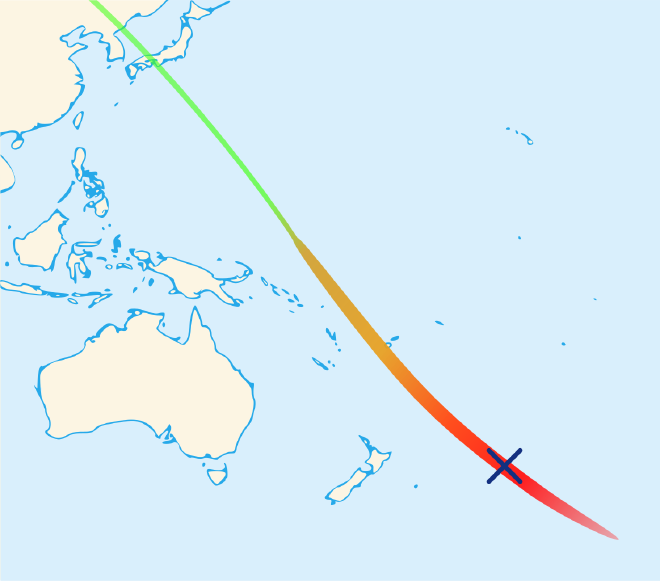

On March 20th, Mir’s orbit had drifted low enough for Progress to begin the deorbit campaign. And on March 23rd 2001, the Progress performed three final burns, aiming the station at the South Pacific.

Mir entered the atmosphere and began to break apart, starting with the solar arrays, before moving on to the radial modules. At around 1.7 times the mass of Skylab, this was the heaviest human-made object to reenter the Earth’s atmosphere. 16 minutes after hitting entry interface, the remaining debris impacted the ocean around 2000 kilometers east of New Zealand. After more than 15 years in space, Mir was gone. Nobody won a taco.

If you’d like to read more about Mir for yourself, here are a few books and documents you can check out. Of course, there’s our old pal Ben Evans and his book The Twentieth-Century in Space. Another great book that covers the whole history of space stations in general is Outposts on the Frontier: A Fifty-Year History of Space Stations by Jay Chladek. And while we’re at it, I’ll just recommend the entire Outward Odyssey series of books which, among other things, includes a The Space Above Us favorite: Bold They Rise.

Clay Morgan’s book “Shuttle-Mir: The United States and Russia Share History’s Highest Stage” was very helpful for these missions and is available for free from NASA. I’d advise against buying this from an online book store since when I did, I got a shoddy printout of the free PDF but with the images all stretched out. Just go to NASA’s website. Another handy resource to check out is The Story of Space Station Mir by David Harland.

Of course, you can also read books by people who lived on Mir, including Tumbleweed by Shannon Lucid and Off the Planet by Jerry Linenger.

There are also a number of useful documents available on NASA’s NTRS service, such as the Mir Mission Chronicle by Sue McDonald, Mir Hardware Heritage by David Portree, and the Phase 1 Program Joint Report.

You can also always find recommended reading and episode sources at the show’s website thespaceabove.us. Eventually. I’m very slow to update the episodes there and even slower to update the sources, but it all gets there in the end.

Lastly, since it’s been a while, I’ll just quickly say that if you’d like to help support the show and get access to some non-essential goodies, such as access to a Discord chat, my own director-style commentaries on top of some well known space movies, and a monthly voice chat, head on over to patreon.com/thespaceaboveus. Or just tell your friends to listen.

Next time.. we’ll do some onboard science, give a ride to a free-flying spartan, and catch up with a blast from the past. Keep your retrorockets firmly strapped in place and your firefly net handy, because this is the second and final flight of a remarkable individual who has been with us since Episode 5: the one, the only, John Glenn.

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass