Episode 167: NASA-5 Part 1 - A Crash Course in Long Duration Spaceflight (Foale on Mir)

Table of Contents

New episode! Mike Foale’s stay on Mir for NASA-5 ended up being so eventful that I had no choice but to break it up into two parts. Thankfully, the same cannot be said for Mir after Progress M-34 comes knocking.

Episode Audio #

Photos #

Progress Collision Video #

If you’d like to see the collision happen in real time, a long uncut video is now available on the TSAU YouTube channel. I found it on the National Archives website but nowhere on YouTube, so hopefully more people have a chance to see it now.

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 167, Long Duration Mir Flight NASA-5 Part 1: A Crash Course in Long Duration Space Flight

First, yes, part one. To be honest, I don’t know what I was thinking even trying to fit this flight into a single episode. Even with splitting this mission into a two-parter, the script for part one is around 50% percent bigger than the average for the show. So don’t think of it as having to wait two weeks to hear the ending, think of it as getting to luxuriate in all the bonkers details of this mission without a huge rush, while also pushing the final episode of the podcast back just a bit more. Aaanyway.

Last time, we covered the 19th flight of Space Shuttle Atlantis: STS-84. The flight carried a number of secondary science payloads, but the primary goal of the mission was to retrieve NASA-4 astronaut Jerry Linenger from the Russian space station Mir, replacing him with NASA-5 astronaut Mike Foale. Linenger had just wrapped up an eventful stint on Mir that included some of the most intense crises we’ve ever seen in human spaceflight. Given that, Foale knew that this mission would be a little different than the spaceflights he had flown in the past. Though I doubt anyone predicted just how different.

One thing I want to note about this episode is that as always, I will be sort of streamlining the sequence of events in order to make a more coherent narrative. That is to say, there is plenty about this mission that I simply won’t have time to cover just so I have any hope of telling a complex story in an understandable way and in a reasonable amount of time. I mention this because like Linenger’s flight, my coverage for NASA-5 is going to largely focus on a small number of high stress events on the station, but I don’t want to give the impression that the entire flight was just wall to wall crazy. But if I’m going to avoid turning every Mir flight into a four-parter, this is how it’s got to be. As always, I recommend that those who are interested in really digging in to the nuance read up on the mission themselves, and I’m always happy to pass along some recommended reading.

One other note is that since this is a Russian incident on a Russian space station, I’ve struggled to find a lot of authoritative documentation. My primary source ended up being a series of three oral histories that Mike Foale gave about a year after returning from Mir, supplemented by several books about Mir. The trouble is that these sources don’t always agree on a number of points. They’re all minor points that are pretty deep in the weeds (like who was holding a laser rangefinder, Lazutkin or Foale?), but it’s enough to bug me, so I wanted to pass it on. It seems likely to me that by combining the confusion of the mission with Foale’s fading memories, some facts may shifted over time, but since I can’t seem to find a definitive account to set the record straight, I’m just going to do the best I can here and when in doubt, assume that Foale is right. The core series of events are consistent enough that I don’t really have any qualms, I just like to be transparent. Anyway, enough preamble.

Mike Foale has been in our narrative for a while now, being selected as an astronaut in the first group hired after the Challenger accident, back in 1987, and then flying for the first time on STS-45, back in 1992. At this point in our narrative he was a veteran space flyer with three shuttle flights and an EVA under his belt. Combine that with the fact that he was raised as both a British and American citizen, navigating two cultures that are fairly similar but still have their differences, and it makes sense why NASA leadership asked him to fly on Mir. Foale was actually not super excited about the prospect. He did want to do a long duration flight someday, serving on the ISS, but he wanted to wait until his kids were a little older. But this was the opportunity that was in front of him and he knew that he was capable of doing it. So while he may have hesitated to get on board at first, once he did get on board he committed to doing whatever it took to have a successful mission.

One of the things it took demonstrates the remarkable willpower and work ethic shared by so much of the astronaut corps. Foale had never been very interested in language, but especially after seeing the experiences of other Mir astronauts, he realized that if he was going to fully integrate with his Mir crew and have a successful mission, he simply had to properly learn Russian. He looked at the task, realized what it took, and accepted the fact that for the next two years he had no choice but to set aside his own hobbies and interests for the sake of the mission. He remarked that people had commented on how he had a high aptitude for language based on how well he had learned Russian, but he didn’t see it that way. In his mind, he simply just put in the time. In his estimation, people thought he just picked up the Russian language with no difficulty because they didn’t see him spending hours a day studying at home, and reading books in Russian before bed. It turns out that if you spend a whole lot of time actively learning and studying something, you can get pretty good at it. Who knew.

Foale’s insights into cultural differences between astronauts and cosmonauts helps to explain why he got along with well with both of his Russian crews. He went into this entire process with a deliberately open mind. Much like Norm Thagard’s efforts, Foale did not just want to be an American on a Russian spacecraft, he wanted to be one of three people in a cohesive crew. When he and his family arrived in Russia for his training, he truly wanted to do things the Russian way, reminding himself to not be too quick to judge, and do as the locals do, even if it’s not what comes naturally. Sometimes this meant adapting to a different style of training, and sometimes it meant eating some kind of gross jiggly fish out of a can, eyeball and all.

He also immediately realized that one particular addition to Star City that seemed like a reasonable and natural development was actually a recipe for failure: the new American housing. As you’ll recall, all the previous Mir astronauts lived in Russian apartments, in Russian apartment buildings. Despite these actually being really upscale apartments by Russian standards, they were still small, cold, and dingy by American standards. Heeding the feedback by earlier astronauts, Russia built a number of American style townhouses for future crews to live in, and Foale and his family were the first to be assigned one of these houses.

At first glance this seems like a really nice gesture, with Russia going out of their way to make the Americans feel more at home, and I have no doubt that it was done with nothing but the best intentions. But Foale immediately saw a problem. It made the Americans separate, other; it put up a barrier. It was physically separated from the Russians; Foale wouldn’t be bumping into crew members and support staff in the hallways of an apartment building. It mentally separated the American crew members from the Russians. By Russian standards, the homes were so ostentatious that Foale couldn’t convince people to come over for casual dinners. It was just too much. It was so much that Foale recalled couples going on walks by the houses and stopping to take photos of themselves with the beautiful Westernized houses. He would hear them come up to the door to take a photo and leave without ringing the bell.

And on top of all of that, the land for the houses used to be a popular park in Star City, but now there were these big American houses there. So from the perspective of the cosmonauts and other workers of Star City, not only did these Americans get a ludicrously luxurious place to live, they did it at the expense of a favorite destination of the locals.

It’s not that Foale really wanted to live in the cramped and dark Russian style apartments. But he recognized that by not doing so, he was already hindering his goal of fully integrating with the crew.

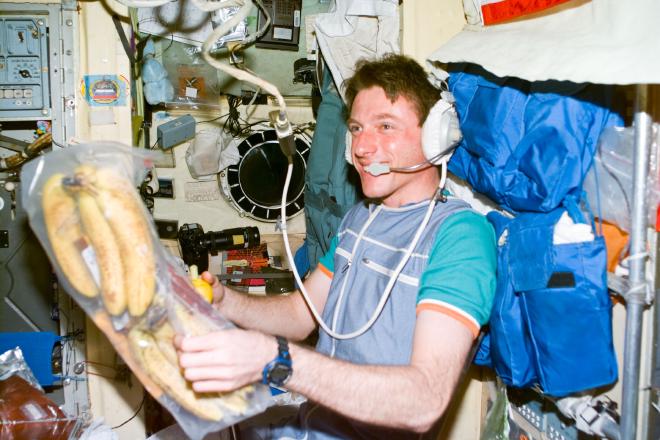

Fast forwarding through Russian training, return to the United States, some last minute family vacations, and the launch, rendezvous, and docking of STS-84, Mike Foale arrived on Mir. Jerry Linenger did as John Blaha had done for him and gave Foale strenuous advice about what to expect and how to handle emergencies. He had him physically put on a respirator, and then close his eyes and find another one, before demonstrating that he could get to the Soyuz quickly. Based on Linenger’s emails home and what Foale had heard beforehand, he had some pretty grim expectations, but was actually pleasantly surprised. Yes, living on Mir looked akin to camping in an overstuffed garage, but to his eyes it was brighter, cleaner, and more homey than he had expected. He could work with this.

One big thing that helped Mike Foale was that he went into this mission keenly aware that it was not a Shuttle mission. Some of his predecessors had tried to approach their stints on Mir with the same frenetic energy as a two week shuttle flight, only to get to the end of the two weeks and realize they still had four months left to go. Foale knew that this was a marathon, not a sprint, and he was totally content to take things day by day. If he didn’t get everything done that he wanted to get done by the end of the day, he wouldn’t beat himself up and stress about it, he’d just pick it up again the next day. If he ran out of scheduled work time, he set his work aside for later and ate and worked out and relaxed. I would imagine that this is actually an incredibly difficult thing to do. Astronauts are driven and hard-working people and they know just how expensive it is to exist in space. But a burnt out mind is a useless mind, so Foale took it easy.

Day to day life proceeded basically as we might expect based on previous missions. Foale commented that despite the limited size of the station it was easy to lose track of someone for much of the day simply due to the amount of clutter floating around. Sasha Lazutkin showed Foale where the fire had broken out in Kvant-1, apparently relishing the chance to tell a good story. Foale said that it was an amusing story, but one with serious undertones. Lazutkin also regularly invited Foale to share some tea with him.

In contrast to Jerry Linenger, Foale made sure to attend every communications pass when Mir was passing over Russian ground stations. They often were not directly relevant to what Foale was working on, but they put him in regular contact with the Russian crew members and helped to break down the barriers between them. He wasn’t just some other guy working somewhere in the ship. He was with them all the time. The ground heard his voice and got to know him, and he got to know the people on the ground. This simple gesture would pay dividends later in the mission.

As the weeks ticked by, Foale had grown frustrated with his inability to help with the day to day maintenance of the station. He didn’t like feeling like he was being put on a pedestal while his crewmates struggled with the dirty and difficult work of keeping the station running. There was an attitude that this was a Russian station and Russians would fix it. But thanks to his efforts to integrate with the crew and get to know the ground, Foale spotted an opportunity. During one ground pass, Commander Tsibliyev was complaining to the ground that he and Lazutkin were getting behind in their tasks because of all the required maintenance, including some menial things like mopping up extra water that condensed on the walls of the station. Foale chimed in with an offer to do it himself. Tsibliyev and the ground considered it, and approved. He was in.

Now, don’t get me wrong, Foale wasn’t exactly stoked to be responsible for sponging up massive blobs of gross water, but it was satisfying to be doing the same work as the rest of the crew and making their lives easier. He also put his computer programming skills to use and wrote a script that sifted through the piles of emails sent from the ground, prioritizing the ones that Tsibliyev actually needed to care about. Tsibliyev was delighted with the time-saving measure. Bit by bit, Foale became someone who could be trusted to help with daily operations. He was wearing down the mental barriers and truly becoming a part of the crew. Somewhat hilariously, at least according to one source, the Russians were surprised to discover that this American was willing to work hard. In order to explain this, they concluded that it must be the English in him, not the American. Oh well.

Around six weeks into the mission, we come to the event that would dominate life on Mir for the remainder of Foale’s stay, as well as the remainder our coverage. As you’ll recall, while Jerry Linenger had been on board, Commander Tsibliyev and Flight Engineer Lazutkin had been tasked with executing a risky test using a Progress resupply vehicle. Typically, it would automatically rendezvous with Mir, using a system called Kurs. Kurs worked great most of the time, but it was somewhat expensive and the Russian space program was pretty strapped for cash. The ground wanted to know how feasible it would be to skip using Kurs entirely and just manually pilot the Progress from Mir, by using a live video feed from onboard Progress. If it worked, Russia couple save a couple million dollars per flight.

Technically, this option was always on the table since it was the backup method in case of Kurs failure. But the idea there was that if Kurs failed, the Progress would likely already be near the station and in a stable situation, allowing the Russian crew to just hop into manual control mode to finish up the last parts of the approach before docking. Instead, with this test, Tsibliyev was expected to use this manual mode to essentially catch the Progress as it flew past the station, null out most of its relative velocity, and guide it in to the docking port. Using some flight dynamics lingo, instead of being responsible for the last few moments of prox ops, Tsibliyev would now have to transition from far field rendezvous to near field rendezvous, and then do the entire final approach. All by hand.

To Linenger’s horror, during the test Tsibliyev had lost the video feed from Progress M-33, making it impossible to control, and the cargo vehicle only narrowly avoided colliding with the station as it cruised by. It was a close call that highlighted just how tricky and dangerous this technique could be, and how cooking up new cost-saving measures on the fly without dedicated training might not be a great idea.

So, of course, we’re about to try again. Same crew, same plan. What could go wrong?

On June 24th, Progress M-34 undocked from the Kvant-1 module and puttered away from the station. Since there was a chance that it wouldn’t be able to re-dock, it had already been stuffed full of garbage that the crew no longer needed and that would eventually burn up with the Progress during reentry. The next day, Progress was on its way back to the station and it was time for the test to begin.

This time there were still some dropouts in the onboard video, but the signal was much more stable, providing Commander Tsibliyev with a view from the front of the Progress. But there were still problems. For one thing, it was difficult to even see Mir in the video. I have been unable to determine the exact approach used by Progress M-34 for this test, but looking at footage shot by the Progress itself, it appears that the plan was to move down the Minus R-bar and then transition to the Plus V-bar. That is, descend from above and then move over to the front, where the Kvant-1 docking port is located.

Long time listeners of the show may have already picked up on a major problem. Waaay back in the Gemini program, while all this rendezvous and docking stuff was first being figured out, this exact scenario was attempted. There was a concern that if an Apollo Lunar Module were to find itself stranded in a low orbit, requiring the Command Module to swoop down and get them, it might be difficult to pick out the LM against the visual backdrop of the moon. After all, it was pretty easy for the gray and lumpy LM to blend in with the gray and lumpy surface of the moon. So in Project Gemini they actually tried this, using the Sahara desert as a proxy for the surface of the moon. The result was that the Gemini commander found it to be nearly impossible to spot the rendezvous target among all the visual clutter from the Earth in the background. In fact, the commander who delivered this assessment will actually make a cameo a little later in the episode to deliver this message in a press briefing.

This issue of a visually distracting background is a big reason why NASA missions rendezvoused with their target from below, allowing them to see it clearly against the black background of space. And that Gemini test was with sharp test pilot eyes, not squinting at a blurry and staticky black and white image playing on a small standard definition television. So suffice it to say that Tsibliyev was having difficulty spotting the station in the Progress video feed.

This would be bad enough, but spotting Mir was super important in this case because the only data Progress was providing was that video feed. There was no information about range, range-rate, relative velocity indicators, anything. Tsibliyev had to just look at the 2D image of Mir with an overlaid grid on the monitor, and try to figure everything out from that.

The result was a disaster. Progress arrived in the vicinity of Mir at far too great a relative velocity, and despite Tsibliyev commanding full braking, it was too late. Lazutkin and Foale had been peering through the windows hoping to spot the Progress. Foale was armed with a handheld laser rangefinder which would have provided critical range and range-rate data. But due to the limited windows on Mir and angle of the Progress approach, neither crewman could see it until it was too late. When Lazutkin saw the Progress emerge from behind some solar arrays that had been blocking his view, he knew right away that there was a major problem, and commanded Foale to head for the Soyuz.

Foale flew towards the Soyuz, getting as far the node, when he heard some loud thumps. He felt the station shudder through his fingertips and then had the strange experience of the seeing the entire station moving around him. A moment later his ears popped. Uh ohhhh.

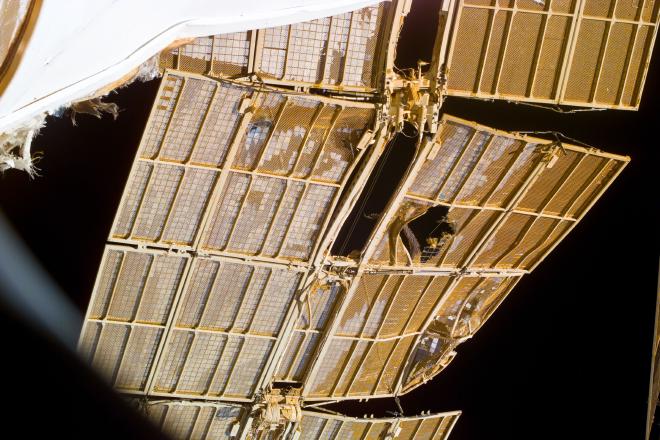

Progress M-34 had missed its intended target of Kvant-1. From what I can tell it didn’t even have a chance because it had been approaching at a crazy 90 degree angle from the capture axis, completely perpendicular to the intended docking port. Instead, it narrowly missed the Base Block and slammed into the large solar arrays extending from the Spektr module. From there, the front of the resupply ship bounced into the Spektr module itself, crushing some radiators and puncturing the hull before tumbling off into space.

This was.. very bad!

The crew’s ears had popped because the onboard atmosphere was escaping at an alarming rate. Commander Tsibliyev calculated that they only had around 24 minutes to either fix the problem or be in the Soyuz so they could abandon the station.

Foale’s first thoughts was that this was it. Surely they would be forced to abandon the station. And actually, in the moment, he found himself to be happy that he would soon be seeing his wife and kids again. But he quickly set that thought aside and got to work helping to resolve the critical situation unfolding around them.

The situation was this.. whether by wrenching the solar array mounts or directly puncturing the hull, Progress M-34 had opened up a hole in the Spektr module of probably around 3 square centimeters, or half an inch. This was actually probably one of the more fortunate possible outcomes of crashing a Progress into Mir. A solar panel and radiator can bend and twist and crush, absorbing energy. If Progress had hit a bare wall or something like a window, it probably would’ve just blasted right through and it would’ve been game over.

Another stroke of luck was that even with the restricted viewing angles, the crew had seen the trajectory of the cargo ship and had a pretty good guess as to where the collision had occurred. Sasha Lazutkin began to disconnect the tangle of cables leading into Spektr with great urgency. Thanks to the way that Mir was designed, there were hundreds of cables snaking their way from module to module, all on the inside of the station, and thus through the airtight hatches. The only way to close the hatch was to disconnect all of the cables.

The crew also worked on freeing the heavy hatch designed to seal Spektr. There were a number of these hatches already in the node. In fact, they were forever in the node, because they were bigger than the exits to the node. But since they were big and bulky and typically were never needed, they were securely fastened to the sides of the node. A little too securely, it turns out. The crew wasted a whole minute of their precious time attempting to unstrap the hatch before giving up and switching to a lighter one they had easier access to.

As Lazutkin worked on unhooking the cables, not all of the connections could be separated or even found, so he resorted to just sawing through them using a kitchen knife, with sparks flying from the live wires. Finally, the passageway was clear and the hatch was free and the crew moved the hatch into place, noting with relief that it was sucked into place all on its own, confirming that the leak was in the Spektr module. The crew’s ears stopped popping. After a few moments it became apparent that that was the only leak and the immediate crisis was over.

Foale said that once the hatch was in place he was actually momentarily annoyed because in the previous few minutes he had accepted that he would soon be going home to be with his family and was looking forward to it. But ever the optimist, he quickly reframed the situation and was again happy, but now because they had just successfully gotten through a serious emergency.

But when I say that the immediate crisis was over, I mean it. The crew were still very much in a crisis situation. In fact, as Foale puts it, right after Spektr was sealed off, quote “all hell started to break loose.” The problem was a lack of electrical power. For one thing, one of Spektr’s primary functions was to use its large solar arrays to provide additional power to the station. And now at least one of those arrays has been crippled by having a spacecraft bounce off it, and the rest were no longer delivering power anyway because Lazutkin disconnected their cables, maybe with a kitchen knife.

But second, when Progress hit Mir it was going pretty fast, on the order of 3 meters per second, or around six and a half miles an hour. That may not sound all that fast, but imagine a car moving at that speed and driving into a building. There is a lot of momentum and stuff is gonna get knocked around and break. The upshot was that now the entire station was rotating and no longer pointing any of its solar arrays at the sun. The station was able to get by using its battery power (after all, that’s what it does during the night portion of every orbit) but that battery power was finite. And while the crew was occupied by sealing the leak, they weren’t shutting down non-essential equipment and soon the batteries were drained. And with no solar panels pointed at the sun, they stayed drained. So the crew now found themselves in a completely dormant space station. No power, no lights, no fans. Nothing.

During the daylight portion of their orbit they were able to get some intermittent power and establish contact with the ground to inform them of the situation. Foale used a neat trick to determine their spin rate, holding his hand out at full arm’s length and looking at how quickly stars moved across the width of his thumb. Knowing that a thumb is about one and a half degrees wide, this told him that they were rotating about 1 to one-and-a-half degrees a second. This is pretty fast for such a big spacecraft. It might not look like it does in the movies, but Mir was tumbling out of control. Foale relayed his estimation of the spin rate to Lazutkin, who agreed, and the crew relayed it to the ground. Once the ground knew their rate of spin and their spin axis they were able to fire Mir’s thrusters and counteract the rotation. It’s interesting to wonder if the crew and ground would have so quickly accepted Foale’s assessment if he hadn’t made so much effort to be a useful and trusted member of the crew earlier in the flight.

The ground stopping the rotation was good but they weren’t out of the woods yet. Mir was no longer tumbling out of control but it also wasn’t pointing at the sun. Foale recalled a trick he had learned from cosmonaut Vladimir Titov, who had flown with Foale on STS-63. Titov told Foale of another time that Mir had lost attitude control and how they had used the thrusters on the Soyuz to reorient the station. The same trick should work now. Tsibliyev was concerned that the station was much larger than it was during Titov’s time and that they might burn through too much Soyuz propellant. If they ran out of Soyuz prop then that was it, they wouldn’t be able to get home. But if power couldn’t be restored then Mir was dead, and the Soyuz actually had a fair amount of margin, so Tsibliyev finally agreed.

Using Soyuz to slew the entire station was a difficult problem. For one thing, nobody was completely sure what the moments of inertia were of the station and its various modules. Put another way, they weren’t sure of the weight distribution and how it would behave when pushed by the Soyuz. For an extreme example of how this can affect things, blow up a balloon and tape some coins to opposite sites. Throw the balloon around and see how it behaves. Now tape all the coins to the same side, right next to each other and do it again. Same mass, different moment of inertia, totally different behavior.

So they would experiment. Tsibliyev would fire the thrusters for a few seconds, and Foale and Lazutkin would look out the windows to determine what the effect was. This was further complicated by the fact that the Soyuz docked at a 45 degree roll angle to the main axis of the station and there were no clear sight lines through the node into the Soyuz. So what Lazutkin and Foale might call “up” in one part of the station was not at all what was considered “up” for Tsibliyev, and communicating the correct direction was deceivingly difficult. And needless to say, nobody anywhere had ever been trained on anything like this. Eventually one of the experimental firings generated a good result. Or rather, it generated the precisely wrong result, meaning they could just reverse that input to achieve the desired effect. After some trial and error, Mir’s solar arrays were once again facing the sun and power was partially restored.

OK, so, great! They’re back on the sun! Everything’s back to normal, right? Not even close. Mir was pointed at the sun now but what did we learn about from LDEF, TSS, and a whole boatload of materials science shuttle flights? Gravity gradient stabilization. If you leave an object in low orbit and don’t control its attitude, assuming the drag effects are small enough, it’s going to orient itself with its long axis along the local vertical. So if Mir was left alone, it would gradually shift to having the axis with the Base Block, Node, and Soyuz, up and down relative to the horizon. Unfortunately, this would not be an ideal attitude for gathering sunlight, and it also meant that when they did get sun, as the angle relative to the sun changed the power would slowly build up, crest, and fade, in a difficult-to-use sine wave. Or I guess cosine wave, but who’s counting.

So what was the crew to do? They used their newfound ability to slew the station in order to employ a technique used by hundreds of satellites and which has a weirdly passionate fan base among certain corners of this podcast’s listenership: spin stabilization. If they could get the solar arrays pointed towards the sun and then gently spin about the imaginary line connecting them to the sun, then they would be gyroscopically stabilized there. With a few more thrusts of the Soyuz, this spin was achieved, and the crew were finally able to enjoy some relatively stable power.

But we’re not quite done with the physics lesson. If you really want some extra credit, pause the podcast, go look up a diagram of Mir, and predict what will happen as it’s spun about the Y axis. Now, for you sane people who just kept listening, I’ll just tell you. The crew only really had a choice between two axes to spin Mir if they wanted stable power, and one of those was not doable with the Soyuz, leaving only one option remaining. It wasn’t the longest axis, and it wasn’t the shortest axis.. it was the intermediate axis. Over the next few orbits, the crew noticed that they were getting less and less electrical power. Lazutkin had a really clever idea and put a piece of paper across a periscope in the Base Block and every few minutes marked where the sun was. The plot revealed that the sun was spiraling away from the center. Foale realized that they were precessing, like when a gyroscope starts to wobble on its base. He also realized that soon the entire space station would flip over, completely away from the sun.

But why? For a much longer and more detailed version of what I’m going to say, look up “Physics Girl” on YouTube and find her video on skateboarding science, but I’ll give the short version. Skateboarders had long noticed that they had no problem spinning their skateboard along the long axis, like a barrel roll, or about the short axis, with the deck always facing up. But they just couldn’t get it to spin end over end and land the trick. It seemed to be impossible. So when legendary skateboarder Rodney Mullen finally found a way to do it by gently guiding the board with his foot, the trick was known as the Impossible. You can try this yourself. Grab something boxy shaped that’s got different lengths in all three dimensions. In the Physics Girl video she suggests a smart phone and as long as you’re careful this works fine. Try tossing it in the air, spinning it about the long axis, no problem. Now try spinning it along the thin axis, with the screen staying pointing up at the ceiling. Again, no problem. But if you try to flip it end over end, it’ll twist in the air and not remain stable. It turns out that your phone, the skateboarders, and the crew of Mir, had all stumbled across the intermediate axis theorem.

If you take anything that’s not symmetrical across all three dimensions, you’ll be able to spin it along its long axis no problem, and theoretically its short axis with no problem but that has other issues we won’t get into. However if you try the intermediate axis, it’s gonna tumble. But if you’re in space, where you’ve got plenty of time for the tumble to play out, you’ll see that it’ll spin normally for a bit, and then suddenly flip, only to continue spinning in that new orientation.. and then it will suddenly flip again, going back and forth! There are great videos of astronauts demonstrating this effect on the ISS and I’ll be sure to post the link. But now it was happening with the entire Mir space station, just in slow motion.

So using his physics background, Foale was able to figure out a) why they were drifting off the sun, b) they would soon flip and face the complete wrong way, but c) soon they’d flip back again. And a stable on-off pattern is easier to work with than an annoying sine wave pattern.

Haha, sorry for the really detailed physics lesson, but I thought Foale’s realization here was really neat and I really wanted to underscore just what a clever moment it was.

Taking advantage of this sort of stable situation, the crew were then able to slowly and laboriously start recharge the station’s batteries, restore critical systems, and begin to get the situation under control. After 30 frantic hours of activity, they could rest. And even better, after 48 hours, they had enough power for the toilet which, as Foale put it, was quote “terribly important.”

So now that the crew has a moment to catch their breath, let’s take a step back and figure out what happened here. Progress collided with the Spektr module at the end of a disastrous manual rendezvous and docking attempt but what set the crew up for failure? As always, it’s a combination of a few different things. First, let’s look at training.

Tsibliyev had received training in how to perform a manual rendezvous, but with a key difference. In Tsibliyev’s training, the Progress had approached Mir from below, making the station clearly visible against the backdrop of space. This is a completely different situation than approaching from above and having to visually track Mir with the ever-changing landscape passing by below it. This was pointed out in a NASA press briefing by an individual who had been asked to leverage his considerable spaceflight expertise to investigate the troubling incidents on Mir: none other than Tom Stafford himself, the very guy who had attempted the tricky from-above rendezvous on Gemini IX-A.

Second, Tsibliyev had been in space for over four months at this point, meaning that any training he did receive was starting to get rusty. This had been a concern for the Space Shuttle commanders with missions lasting only two weeks, leading to the introduction of the PILOT experiment, which allowed commanders and pilots to perform simulated shuttle landings during the mission itself. Four months is a lot of time for a critical skill set to fade, and Tsibliyev did make some mistakes during the rendezvous. On their own they shouldn’t have been enough to lead to the collision, but when added up with everything else, it made a bad situation worse.

Third, this was a used Progress, literally stuffed full of garbage. As I touched on in the NASA-4 episode, this is an important detail because rather than being securely packed by a team of dedicated technicians, Progress M-34 was packed by three busy guys who had to manually keep track of everything that went inside and where it ended up in order to determine overall mass and the center of mass. And even if they did know the center of mass, it was likely to shift around as the trash shifted around in the weightless vehicle. And indeed, it seems likely that the Progress had more mass than was expected, which would have impacted the efficacy of its thruster firings.

Fourth, when the ground sent Progress back towards Mir, its arrival trajectory was within specifications, but right near the margins. This meant that it was going faster than was ideal and was not on the ideal path. At the same time, the thruster performance on the Progress was also within specifications but under the nominal values. That is, the thrusters were technically OK, but weaker than was ideal. The combination of a faster Progress and weaker thrusters resulted in a far more sluggish vehicle. We actually have to consider this sort of thing a lot at my day job on OSAM-1. If the launch vehicle drops us off at the extremes of our orbital insertion requirements and the thrusters under-perform at the extremes of their requirements and maybe the first few burns are cold and the next few burns are hot.. can our rendezvous sequence still close successfully? In the case of the Progress the answer should have been technically yes, but there was less and less margin for error.

Fifth, given all of the above, the procedures and planned maneuvers given to Tsibliyev were inadequate. The braking sequence needed to happen sooner and burn for longer. According to Tom Stafford, Russia actually took five of their best pilots and put them in the simulator with the same situation and same procedures as Tsibliyev. Not only did all five of them fail to successfully complete the docking, they all hit Spektr! And it’s not like there was no way to know this ahead of time. The ground could have performed some engineering test burns with the Progress while still far from the station and evaluated how they affected its orbit, providing insight into how the combination of spacecraft mass and thruster performance actually affected each maneuver’s delta-v. This could have revealed the sluggish nature of this particular spacecraft in this particular configuration. I honestly have no idea if such a calibration was performed but given what happened, it seems unlikely.

So when we combine all of these factors together I think we can summarize the incident like this: the experimental rendezvous was always risky and of dubious value, and was hampered by a lack of adequate training, a lack of adequate information for the commander, an unusually fast approach, unusually poorly performing thrusters, and mistakes by the crew. The result plunged Mir and its crew into days of stress and chaos that very nearly resulted in the loss of the station or even the loss of the crew, and did result in the depressurization and emergency sealing of one of its modules. All in an effort to save a few tens of millions of dollars.

Next time, Mike Foale still has a ways to go until he sees Space Shuttle Atlantis in the window. We’ll meet a new Russian crew, perform spacewalks both outside and inside the station, stab some more space hardware with a knife, and wonder how many tons of water are hiding inside Mir’s walls.

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass.