Episode 158: NASA-3 - Blaha Blast (Blaha on Mir)

Table of Contents

John Blaha will stay on Mir for four months and will encounter unexpected bubbles, limited communications, fourteen hour days, and the first ever NASA in-space handover. Let’s just hope his sanity survives the next few months.

Episode Audio #

Photos #

I took these two photos when I met Blaha for the second time back in 2018!

T-shirt #

This is kind of out of left field, but one time the folks on the The Space Above Us Patreon chat played some Jackbox games, including the one where you make T-shirts based on shuffled-up images and phrases. Somehow this happened. I really should have bought the shirt.

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 158. Long Duration Mir Flight NASA-3: Blaha Blast

Last time, we covered the fifth flight of the space shuttle to the Russian space station Mir, STS-79. Atlantis once again docked to the station using the handy-dandy docking module that had been attached to the Kristall Module a few flights back, and the crew immediately got to work transferring literally tons of equipment in both directions across the hatch. Well, almost immediately. First the Russian commander made them enjoy a meal and relax together.. but then the frantic activity began. Among the thousands of kilograms of equipment being transferred to Mir was one particularly specialized piece of equipment: John Blaha. Today we’ll follow Blaha over to the Russian space station, wave goodbye to Atlantis, and settle in for a four month stay on orbit.

Before we begin, two quick notes. First, thank you to podcast listener Jonas Reilly for the amazing episode title suggestion. Second, I have something a little unusual to mention: an anti-recommendation. Over the years here I’ve recommended a lot of excellent books. Examples include Failure is Not an Option by Gene Kranz, Falling to Earth by Al Worden, Into the Black by Rowland White, and dozens more. There are so many incredible books about space out there that are worth picking up and enjoying. But today I want to specifically warn you about a book to avoid: “Dragonfly: NASA and the Crisis Aboard Mir” by Brian Burrough. Normally I wouldn’t bother with this, but Dragonfly came up so often in my research that I thought it would be best to do a little public service announcement. Dragonfly was published in December of 1998, just as the Shuttle-Mir program was winding down. It features a number of astronaut interviews and insider stories, including exciting and previously unknown details about what life was like on the Russian station. The problem is.. it’s nonsense. When I started to read it I noticed a few odd errors here and there, but eventually it got so personal and speculative that I came to distrust it. Astronauts in the book later stated that they had essentially been tricked into the interviews under false pretenses and that the contents of the book are a work of fiction.

From what I can tell, it’s not complete nonsense, but it gets a lot of basic facts wrong and presents some kind-of-wild conclusions as if they are facts. It strikes me an author looking to zhuzh up an already exciting story by adding speculative conflict and drama, which isn’t a great way to learn history.

The reason I bring this up is that the book is weirdly popular. I found a lot of other sources that cite it, to the point that it was difficult for me to be 100% sure if my information was free of influence from this corrupting book. So I wanted to mention it because if you decide to learn more about the Shuttle-Mir program there’s a good chance you’ll encounter it on your own, either directly or through other sources.

Alright, with that out of the way, let’s get back to the matter at hand. When we last saw John Blaha, it was as he floated through the Kristall module, moving in to his new orbital home. But how did we get to this point? Blaha, of course, is a shuttle pilot and commander who has been with us since being selected as an astronaut in 1980. But he specifically became interested in the idea of living and working on Mir when he first attended an Association of Space Explorers Conference in Berlin in October of 1991. While there, after the formal part of the conference was over, he spoke with some cosmonauts and saw a video about Mir, and it really piqued his interest. It also occurred to him that at his age it was unlikely that he would get to serve on the International Space Station, which was still a number of years away. As the Shuttle-Mir program evolved he expressed interest in participating and before long he was packing his bags for Russia.

Just like Norm Thagard and Shannon Lucid, John Blaha’s Mir experience included a lengthy stay in Star City where he trained to learn the Russian language as well as the systems and procedures of Mir and the Soyuz spacecraft. Upon arriving in Russia he immediately hit a problem that Shannon Lucid also encountered: learning Russian is hard. In an oral history given a few years after his return to Earth, he specifically called out the Russian-language-training as one of the biggest issues with the program. When he met with the language experts at Monterey Language Services, they told him how they had told NASA that thanks to the cold war they had been teaching Russian for decades and knew that it took about two years of dedicated study to properly learn it. According to Monterey, NASA’s response was that astronauts are smarter than normal people and they could do it in five months. I mean.. astronauts are smart people, but I’m not sure language learning works that way.

As for the space systems training, Blaha had similar observations as Lucid, which makes sense since they were often training side by side. Blaha noted that in America the astronauts train the easy but expensive way. Astronauts practically live inside high fidelity simulators with dedicated training crews for month after month. By the time they climb into their real spacecraft it feels like home. In Russia you get a classroom, a blackboard, and an instructor with some chalk. I had to laugh at this because while it wasn’t exactly the same thing, my first math professor in college was Russian and my mind was sort of blown when she did the exact same thing. No book, no handouts, no visuals. Just Professor Sternberg with her notes, a blackboard, and a lot of chalk.

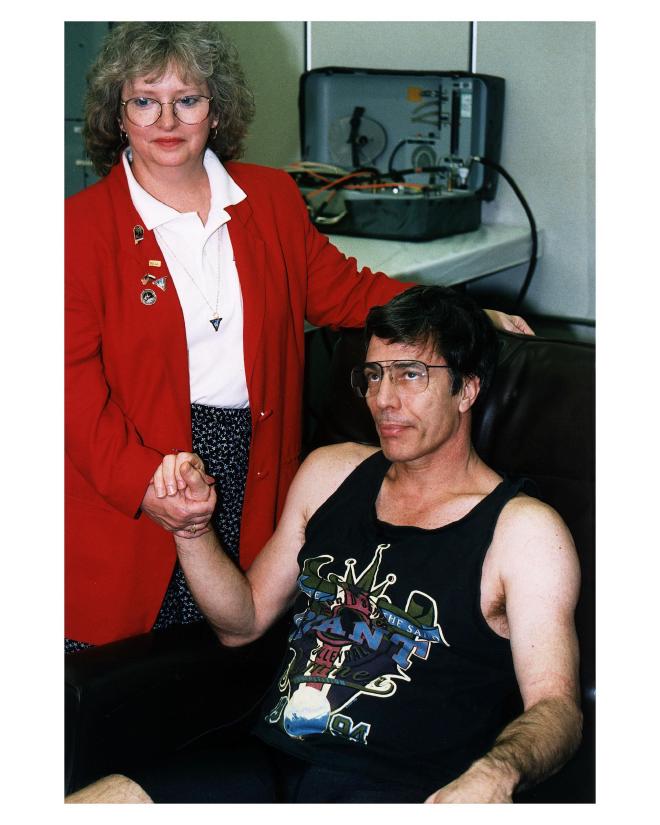

One big benefit Blaha had was that his wife Brenda joined him for his lengthy stay in Russia. They had a weekly routine of exploring the country and enjoying what the local cities had to offer, but Blaha painted a rather bleak picture of what his personal experience was mostly like. This was highlighted when after returning home, Brenda showed him two big photo books she had made, documenting their 18 months in Russia. Blaha said that they were really great books but not what he saw of Russia. What he saw was a desk in a small little room in his apartment where he studied all day every day!

I will be very curious to see how NASA and Russia’s approach to training for long duration flights changes in the future. It seems to me that few on the NASA side fully appreciated what sort of sacrifice would be required of the Mir crews, perhaps even the Mir crews themselves!

And speaking of crews, let’s meet the Russian crewmates that John Blaha would be spending over four months with. Blaha had trained with cosmonauts Gennadi Manakov and Pavel Vinogradov but just weeks before their scheduled liftoff, Manakov and Vinogradov were replaced. During a routine medical checkup, it was discovered that Manakov had a worrying heart rhythm and would be unable to fly. Since Russia preferred to swap entire crews, Vinogradov was also replaced. But don’t feel too bad, we’ll see him a couple times during the ISS era.

So with the clock ticking, Blaha scrambled to meet and get to know his new orbital crewmates. But with so little time, the American and Russian sides of the crew would essentially be strangers.

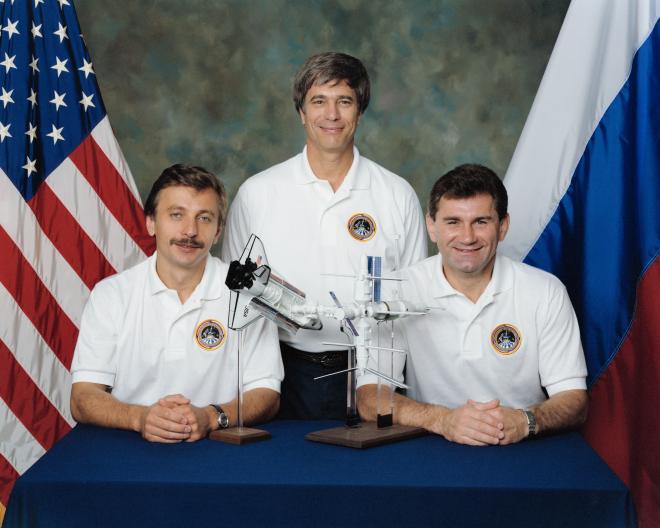

But that doesn’t mean the new crew has to be strangers to us. We actually briefly met them during the end of Shannon Lucid’s stay, since they arrived a few weeks before she departed, but let’s meet them properly.

Commanding the mission was Valery Korzun. Valery Korzun was born on March 5th, 1953 in Krasny Sulin, which is part of Rostov Oblast, in the South-West of Russia. He graduated from the Kachin Military Aviation College before joining the Soviet Air Force, eventually commanding an air force squadron. In 1987 he was selected as a cosmonaut and this is his first of two flights.

Joining Korzun in the Soyuz capsule was the mission’s Flight Engineer, Aleksandr Kaleri. Aleksandr Kaleri was born on May 13th, 1956 in Yurmala, Latvia. He graduated from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology before heading off to work at Energia, the major Russian spaceflight corporation. He worked on design and technical documentation as well as full scale tests of Mir before being selected as a cosmonaut in 1984. He served as a backup crew member for the third Mir mission before flying there himself five years later in 1992. That flight was 145 days long and included a spacewalk. Today’s mission marks his second of five flights so far, including the final crewed mission to Mir.

On August 17th, 1996, Korzun, Kaleri, and French researcher Claudie Haigneré rocketed out of the Baikonur Cosmodrome and set their sites on Mir. Haigneré would only be staying onboard briefly during the crew handover, but Korzun and Kaleri were in it for the long haul.

Just shy of 30 days later, STS-79 launched and soon delivered John Blaha to his orbital destination, completing the Mir EO-22 crew.

As I mentioned last time, Blaha’s first task was to transfer his Soyuz seat liner from Atlantis and make sure it was properly installed in the Russian spacecraft in case of an emergency. After the seat liner was installed and he performed a check of his entry spacesuit, he became a part of the Mir crew and got to work.

Part of that work involved trying to learn as much as possible about life on Mir from Shannon Lucid in the five days or so that Atlantis would be there. This is actually pretty notable since it marks the first time that an outgoing NASA crew member has briefed an incoming NASA crew member while in space. All the Skylab crews launched after the previous crew had already landed. And even Norm Thagard, who had preceded Lucid on Mir, had been home for almost a year before she launched. So while the Russians had been doing this for years, this in-space handover was a new concept for NASA. More on the handover later.

As Blaha settled in, he noted the impressive roominess of the facility. His estimate was that it was around five times larger than the shuttle, which is a pretty impressive estimate. In reality Mir’s 351 cubic meters of habitable volume is 4.7 times bigger than the shuttle’s 74 cubic meters of space. When you consider that the shuttle often had a crew size of seven and Mir usually only had a crew size of three, that means that Blaha had 11 times more room than he was used to. What luxury! In a series of emails home, he mentioned that while two of the modules were new inside, quote “The other four modules look a bit used - as you could imagine a house looking after people have lived in it in orbit for 10 or 11 years, without the advantage of bringing the vehicle home and letting it be cleaned up on the ground.” This made me laugh because it’s not really an analogy since that’s.. actually true? Regardless of how lived-in it may look, Blaha called it an “incredible space station”.

But actually, early in the mission John didn’t have too much time to look around. Before the shuttle had even departed, one of his major experiments was running into trouble. The somewhat generically named Biotechnology System would be studying the effects of low gravity on mammalian cartilage cells. But notably, it wasn’t quite studying weightlessness. Inside this experiment was a drum that could be made to rotate at different speeds. This would allow the experiment to dial in the precise acceleration it wanted. Want zero-g? Stop the spinning. Want one-g? Well, do the math and figure out the precise rotation rate required. And for something in between, just pick a rate in between. So given that setup, can you guess where we’re going with this? Yeah. The experiment stopped rotating.

This was a pretty big deal, so Blaha leapt into action. The troubleshooting procedures provided didn’t seem to do the trick and the clock was ticking. STS-79 Mission Specialist Jay Apt helped out by taking a bunch of digital photos and downlinking them to the ground so the project scientists could try to figure out what was wrong. The ground suggested more fixes, Blaha tried them, but they were still out of luck. Blaha actually became so absorbed in trying to fix it that he had to skip the big formal goodbye when the STS-79 crew left, instead dedicating his time to repairing the stricken experiment.

Eventually the ground came up with a solution. By studying the photos they noticed that a data cable had come loose and that was the cause of the problem. All they needed to tell Blaha to do was to access the cable and plug it back in. Given the bizarrely strict and bureaucratic nature of communication from the ground to Mir, this actually had the potential to be a show stopper, requiring days of approval. But in this case the Russian flight director helped clear the way and the procedure was soon uplinked and Blaha was able to get everything back on track.

A scientist working on the experiment later said quote “It ain’t Apollo 13, but from a scientist’s perspective, we pulled it off and saved that experiment.”

With the Biotechnology System fixed, Blaha was able to turn to his other experiments and continue to dive into his work. This actually made him the first American to have this ability, since both Thagard and Lucid were stuck waiting months for their experiments to arrive on Spektr and Priroda, respectively. Both modules had their launches delayed and left the American crew members with little to do in the early parts of their missions. As such, they were more or less forced to ease into their routine, courtesy of some involuntary downtime. So whether it was a blessing or a curse, Blaha had plenty to do. And actually, it’s kind of funny that he was the first Mir astronaut to benefit from this since Blaha was also the first and only of those seven people who was not a scientist. He came from a pilot background. In fact, as he pointed out in his oral history, among the five people who flew to Mir while he was still with NASA, he was the only non-scientist but also the only one who was able to complete all his scientific work without major disruptions. Funny how things work out sometimes.

Joining the Biotechnology System was the Diffusion-controlled Crystallization Apparatus, or DCAM. DCAM was actually a holdover from Lucid’s flight and actually didn’t require too much interaction, so was not a huge addition to the workload. It was studying the growth of crystals across a semi-permeable membrane. Another crystal-related experiment was the Binary Colloidal Alloy Tests. In this experiment, two different types of crystals were sort of grown into each other over time. So now we’re in double crystal territory! The technology had applications in liquid crystal displays and drugs that dissolve in the body over time, among other things. This experiment was really a precursor to one planned on the ISS, so ten different samples were provided, which Blaha had to photograph twice a day for 90 days. The results would help decide how to proceed with the followup experiment.

Some experiments were studying how Blaha interacted with the station, again with an eye towards the ISS. In one, a special foot restraint was provided, which measured how much force Blaha used when keeping himself in place. And in another, an instrumented push-off pad measured how much force he used in order to get around. I would imagine that while this is a pretty straightforward test, the results would be extremely helpful when designing equipment for the crew to use on the ISS, while also ensuring that mass and money were saved by not over-engineering it.

Another experiment sought to measure the influence of weak but persistent acceleration from stuff like atmospheric drag as the station flew through the extremely thin air outside. By using a ball in a fluid-filled tube and a little ingenuity, scientists were able to craft an experiment that measure accelerations as low as 50 nano-Gs. Nanogravity! That’s even better than microgravity!

Blaha also put on his farmer hat and harvested a sample of wheat that had been planted by Lucid and had been growing on the station. Most of it was frozen for the trip back to Earth but some of it was replanted by the astronaut, and allowed to grow for a bit before it too was frozen for later analysis. This kind of research has obvious applications for long duration spaceflight, where growing plants can help replenish oxygen in the onboard atmosphere and also provide fresh food. Plus, I imagine that the psychological effect of maintaining a little garden inside a tin can is worth something too.

When Blaha wasn’t working on the various onboard experiments, he was exercising, preparing food, talking to the ground, and enjoying the views out the window. That last activity was aided by a laptop that showed a ground-track of Mir along with times that it would be flying over particular locations. Blaha could set an alarm and take a brief break to admire the view of a particular city or mountain range from hundreds of kilometers up.

But one thing he didn’t do a ton of was interact with his crewmates. This was interesting to me because it really contrasted with Lucid’s experience on NASA-2. Lucid had struggled a lot with Russian, but once she and her crew developed their “cosmic language” they were able to communicate and enjoy each other’s company. Blaha said that he actually did just fine with the language, likely benefiting from six months more practice than Lucid, but that he didn’t really do much with Korzun and Kaleri. It doesn’t sound like there was any acrimony or bitterness, it’s just that with the last minute crew swap, Blaha and the Russians were mostly strangers. They were all professionals and able to work together to get their jobs done, but I never saw any stories with the same good-time feels as Lucid, Onufriyenko, and Usachov enjoying a nice bag of Jell-o.

Blaha himself estimated that over the four month mission he maybe did stuff with the cosmonauts only 15 to 20 times, which works out to around once a week. During the day they gathered every 90 minutes or so to participate in communications passes with the ground, and they would sometimes eat together, but with Blaha’s time occupied by experiments, and the Russians putting in 16 hour days, half of which was dedicated to maintenance of the station, their paths didn’t cross all that much. I would imagine that even for professionals that would become draining after a while.

Blaha relaxed by winding down most days with one of 50 onboard movies or some taped NFL games. He also enjoyed using the ham radio setup on the station to talk to friends, family, and some lucky amateur radio enthusiasts around the world. In his oral history he said that the biggest struggle was the extended period away from his wife. He figured that if he was able to simply beam up to Mir at the start of the week and beam home to his wife on the weekends he could’ve gone on for four or five years living and working on the station. Maybe someday access to space will be routine enough to support a commuting astronaut, but for now Blaha had to content himself with radio calls and uplinked emails.

But the isolation wasn’t the only frustration for Blaha’s mission. Over time a disconnect grew between Blaha and his ground support team. Every day a new Form 24, their daily schedule, was uplinked to the crew. But to Blaha’s dismay, the schedule was often far from realistic. Experiments wouldn’t be allotted an appropriate amount of time, and setup time was often neglected entirely. Sure, maybe actually performing the experiment would only take an hour, but the schedule wasn’t accounting for the fact that it might take him several hours to gather the required equipment in the first place. This wasn’t helped by the fact that Mir was cluttered with decades worth of equipment as well as literal bags of trash waiting for a fiery ride back to Earth onboard a Progress resupply ship. On top of that, especially early in the mission, much of the station was kept dark in order to save electricity, thanks to some old and under-performing solar arrays.

Part of this disconnect was caused by the limited and sluggish communication caused by the rigid Russian process. Everything had to be reviewed and approved by Russian ground controllers, and then uplinked through Form 24. But if this disconnect sounds familiar, I’m right there with you. Because this reminds me of nothing so much as Skylab 4 all over again. Support staff on the ground didn’t understand the realities of life on Mir and didn’t realize what they were signing Blaha up for or why he was struggling. And Blaha didn’t understand why the ground kept setting him up for failure. We didn’t get anything nearly as dramatic as Skylab 4, but combined with the higher levels of isolation, it was a recipe for frustration and weariness on Blaha’s part.

The long distance communication also caused a completely unique problem partway through the mission. Blaha had arrived at Mir in September 1996 and wouldn’t be coming home until January 1997. And what’s that square in the middle of those two dates? The 1996 election season. Everything from city council all the way up to President of United States was on the docket, with that last contest coming down to incumbent-president Bill Clinton, Republican challenger Senator Bob Dole, and businessman Ross Perot running as a third party challenger from the Reform Party. Bill Clinton eventually emerged victorious, but John Blaha did not have a say in the matter one way or the other. Absentee ballots weren’t ready when he departed for orbit, and there was no legal method to allow him to vote from space. It just wasn’t something that had been considered when the law was written.

Blaha wouldn’t benefit from it, but the next year a new law was passed in Texas that remedied the situation. In August of 1997, Texas Secretary of State Tony Garza started off a press conference by introducing himself as quote “the jerk who wouldn’t let the astronaut vote last November” before providing details about the new law. Astronauts could now send encrypted emails down to NASA who could forward them along to county election officials who would be able to officially record their vote. We’ll get to see it in action just a little bit down the road on another Mir mission. But in a funny little twist it seems that the Russians have once again just beaten us to a notable spaceflight milestone. The first votes ever cast from orbit were sent down from none other than Yuri Onufriyenko and Yuri Usachov, the previous Mir crew, just a few months earlier in June of 1996.

One big highlight of the mission came in late November when a Progress resupply ship arrived. This was big news for a couple of reasons. For one thing, they could stuff the departing Progress full of garbage, including 600, yes, 600 liters of urine, and send it off to burn up on reentry. But also, when the new Progress arrived the crew could enjoy care packages from their family and from their ground support teams, as well as something us Earthlings take for granted: different-smelling air. Lucid had actually remarked on this during her stay. It wasn’t that the air on a Progress smelled good or bad, it’s that it smelled different. And that was appreciated by the crew. As always seems to happen, all other work ceased for a bit while the crew dug into their care packages and enjoyed their connection to Earth.

But the Progress was also a big deal because it enabled a spacewalk for the Russian crew, presumably by delivering some of the needed equipment. Solar panels degrade over time in space, and the solar panels on Mir were providing much less power than when they were first installed over a decade ago. What they really needed was a new set of solar arrays. And hey, what’s this attached to the Docking Module? A new set of solar arrays! Specifically, the “Cooperative Solar Array”, made in collaboration, or i guess cooperation, between NASA and Russia. Yep, remember back on STS-74 when I briefly mentioned that the DM was a convenient place to stick some solar arrays which would later be moved to a permanent location by some cosmonauts on a future EVA? Well, that EVA actually happened on the previous Mir mission, with Lucid holding down the fort inside and Onufriyenko and Usachov moving the solar panels from the docking module to the Kristall module. But they didn’t actually hook them up to anything, so that’s what we’re going to do today!

With Blaha keeping an eye on systems inside, Korzun and Kaleri suited up and climbed out onto the exterior of the space station. They made their way over to the Kvant module and began sifting through the various cables that had accreted over the years, seeking out the one they needed to disconnect. They hooked up a 22 meter extension cable to the Cooperative Solar Array, and routed it over to the socket where the old solar array was hooked up. Next they disconnected the old array, connected the new array to its socket, and with that, 6 kilowatts of power began to flow into the station. After six hours outside, the Russian crew came back inside and the crew enjoyed a big meal together.

The solar panel was working great, but they soon discovered that somewhere in all that cable rerouting, the antenna for the amateur radio setup had been disconnected. I imagine this was especially disappointing to Blaha, who had really taken to the airwaves. But Blaha didn’t have to wait long for the radio to be fixed. The next week the Russian crew suited up once more and exited the airlock for their second EVA. The main goal was to install a new Kurz rendezvous radar antenna on the docking module, which would enable automated dockings by the Progress and Soyuz vehicles. This task was made especially tricky by the small nuts and bolts and by bulky spacesuits but was completed successfully. The EV crew then continued on to fix the connection of the amateur radio antenna.

The spacewalks clearly made an impact on Blaha, who later said quote “I will forever remember the incredible views of these two cosmonauts floating in space, silhouetted against the black of space, with planet Earth rotating by us below. I will forever remember the sounds of strain in their breathing when the workload was intense. And, finally, I will never forget the incredible feeling of accomplishment after the job was complete, and everyone was safely inside the Mir Space Station.”

As the four month mission wore on, Blaha faced his own fair share of troubleshooting. The Biotechnology System, with its cartilage cells and rotating drum, had started forming bubbles in the cellular medium. The bubbles eventually grew to as much as 20% of the total volume. Blaha swapped out the medium and tried some other troubleshooting techniques but nothing could fix the bubbles. But since the bubbles sort of stayed on their own and weren’t obviously interfering, the scientists on the ground decided to stop trying to fix it and simply added a similar amount of bubbles to the copies of the experiment they had running on the ground as a control.

Just two days before STS-81 launched to come bring Blaha home, he was alarmed to hear a loud clattering noise in the Spektr module. Upon investigation, he discovered that one of the two cooling fans in the life science freezer had broken and was just banging around. This was.. very bad! Inside that freezer were all of the life sciences samples that Blaha had been so diligently collecting for months. If the freezer failed it would destroy all of the samples and all of those experiments. While Blaha got to work on trying to repair the freezer, folks on the ground went into super-scramble mode, getting a replacement fan and a backup fan and rushing them over to Florida to load into the shuttle, all in less than 36 hours. It was actually pretty lucky that this fan broke when it did. Blaha was able to remove the broken fan and get the freezer working with just one, but that wasn’t sustainable. If there hadn’t already been a shuttle mission on the way, the samples would have been doomed. Instead, thanks to quick action by Blaha and people on the ground, the samples were eventually saved and the freezer would now have an additional layer of redundancy thanks to its backup fan.

On January 15th, 1997, a familiar sight greeted Blaha out the window. Space Shuttle Atlantis had once again returned to the Russian station. All that stood between the astronaut and returning home to his wife was a few frantic days of activity as he transferred the results from his experiments and briefed incoming Mir astronaut Jerry Linenger.

And it turns out, this is a frantic few days that Blaha had been putting a lot of thought into. Not just because it meant that he would soon be returning home, but because this was when the handover from Blaha to Linenger would take place. Blaha had been thinking about this because, well, to be blunt, he was not very impressed with the handover he got from Shannon Lucid. He didn’t seem to be angry with his friend and former crewmate, but he also wasn’t happy. When asked in an oral history if Lucid had provided valuable information during their swap, Blaha responded “Some. But all through my debrief–and this I never understood, to this day I don’t understand it –in my view, I didn’t get a real good handover.” He later would specifically use the word “disappointed” to describe his feelings about it. This is pretty surprising, considering that Blaha and Lucid had worked so well together on STS-43 and STS-58, but once you take a step back and look at it, you can see how this situation happened.

First, it’s important to recognize that this had never happened before. As I mentioned earlier in the episode, this on-orbit handover had never happened between two NASA astronauts. Each Skylab crew landed before the next one launched, and Norm Thagard had been back on Earth for almost a year before Lucid lifted off.

Second, I think this is another example of the disconnect between the ground and space once again rearing its ugly head. Inadequate time had been provided for Lucid and Blaha to work through everything during the five days the shuttle was docked to the station. Blaha specifically called this out when planning the handover to Linenger, asking the ground to provide a schedule, and requesting specific tasks to be reassigned away from Linenger to other crew members. So I think one part of the problem was just a simple lack of experience leading to nobody putting much thought or planning into what turned out to be a critical period. I doubt even Blaha recognized its importance until he suddenly found himself on the other side of the hatch, watching the orbiter fly away.

Third, Lucid had less to do when arriving at the station. A lot of her work was being delivered aboard the Priroda module, which was still months away from liftoff. This likely gave her ample time to figure stuff out for herself with no pressure. She literally had little to do but learn how to live on Mir. In Blaha’s case, he was thrown into a frantic science experiment troubleshooting effort before Atlantis had even departed, giving him little time to acclimate before being in the thick of things.

Blaha believed so strongly in the importance of this handover that he had been sending down detailed emails every few weeks in an attempt to convey to Linenger all the stuff that nobody on the ground was going to teach him. He also spent months developing a detailed checklist to ensure that he didn’t miss anything when showing Linenger around. On top of that, once back on Earth he worked with mission planners to continue to improve handovers between future astronauts on Mir.

This unfortunate struggle sounds like a real bummer for John Blaha, but it strikes me that this is kind of what the Shuttle-Mir program was all about. It was able discovering what NASA didn’t know they didn’t know, so when it came time to work on the ISS, most of the painful lessons would be behind them. I was curious to hear what a handover looked like in the ISS days, so I reached out to someone who had been through one himself, friend of the show astronaut Dan Tani.

Dan noted a few things working in his favor when he arrived for Expedition 16 in October of 2007. For one thing, NASA had built their segment of the ISS and had been working with it since day one. So they clearly had a much better picture of its systems, the items onboard the station and their location, as well as general day to day life. Tani also benefited from video conferences with Clay Anderson, the crew member he’d be replacing. Once at the station, 20 hours of time spread across almost 11 days was dedicated to Anderson showing Tani around and getting him comfortable with what he’d be doing as a Flight Engineer. And then on top of that, once the shuttle departed, Tani could easily get in contact with Anderson again if another question came up. This is quite a contrast to Blaha being only the third American crew member on a station that was foreign in several ways, relying on a compressed training completed in another language, a few frantic hours of information from his predecessor, and the occasional email or ham radio call for followup questions.

It’s also telling that in his oral history interview, Blaha made it clear that there were no hard feelings, but stressed that he thought NASA had missed out on some lessons learned during the Shuttle-Mir program. His feelings were that NASA failed to properly capture knowledge about long-duration versus short-duration flight. He later put it another way saying that NASA learned a lot about planning and flying logistics rendezvous missions to a space station, but that once the hatch closed, the only Americans who learned about long-duration spaceflight were the seven Americans who remained on Mir. Having read a number of interviews with ground-based support staff I think Blaha might be overstating things a little here, but the fact that an astronaut who had been with the program for 16 years and who had commanded two shuttle missions would feel so strongly and be so blunt, even two years after returning to Earth, is certainly something to consider.

Just shy of five days after Atlantis docked, it once again departed, this time with Blaha back on the orbiter side of the hatch and his time on Mir behind him. Despite what seems to be a somewhat tough stint on the station, I’m sure Blaha would have preferred his mission to the uh.. “exciting” events met by his successor. But that’s a story for another day.

After reentry and landing at the Kennedy Space Center, Blaha was back on Earth after 128 days, 5 hours, 29 minutes, and 42 seconds in space. He said he was absolutely stunned at the strength of gravity, and seemed happy to accommodate the researchers who had asked him to be carried off of Atlantis so they could better study his return to his home planet.

While Blaha’s mission was unequivocally a success, I think his post-mission self would agree with something he had said beforehand: quote Every shuttle flight I’ve flown, I’ve never wanted to come home on entry day. I really enjoyed being in orbit. I’ve always said I would stay there forever. I think that on this mission, I will define what ‘ever’ is.”

I have had the privilege of meeting John Blaha twice thanks to his frequent appearances at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, and I can confirm that he is a fascinating dude. Among the folks in the The Space Above Us Patreon chatroom he’s become something of a mascot of the show, so it’s sad to see him go. We’ll send him off one last time when we cover STS-81 in full, but for now, we’ll just say Ad Astra, John.

Next time.. the Wake Shield Facility is back for one last hurrah, the airlock hatch will make a few enemies, and Story Musgrave surfs on a wave of plasma at 28,000 kilometers per hour.

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass.