Episode 171: STS-86 - Does He Stay Or Does He Go Now? (Wolf to Mir)

Table of Contents

Dave Wolf didn’t think he was going to Mir for another six months, but when Russia decides Wendy Lawrence is too short, schedules change. Though if Congress has anything to say about it, Wolf might not be going anywhere after all.

Episode Audio #

Also, “MEEP!”

Photos #

Post-Flight Presentation #

If you’d like to see the mission in motion you can check out the post-flight presentation here:

Mir Safety Hearing #

If you want to see the House hearing on Mir safety you can find that here: https://c-span.org/video/?91415-1/mir-safety-feasibility For a fun brain-melting time, try watching it at 2x speed. Good luck not falling into a trance.

Wake Up Calls #

Thanks again to TSAU listener broe91 for putting together a Spotify playlist of all the songs used as wakeup calls for the mission. This mission is a little more patriotic in nature than the last time we did this, but that’s still fun!

Transcript #

NOTE: This transcript was made by me just copying and pasting the script that I read to make the podcast. I often tweak the phrasing on the fly and then forget to update the script, so this is not guaranteed to align perfectly with the episode audio, but it should be pretty close. Also, since these are really only intended to be read by myself, I might use some funky punctuation to help remind myself how I want a sentence to flow, so don’t look to these as a grammar reference. If you notice any egregious transcription errors or notes to myself that I neglected to remove, feel free to let me know and I’ll fix it.

Hello, and welcome to The Space Above Us. Episode 171, Space Shuttle flight 87, STS-86: Does He Stay Or Does He Go Now?

Before we begin, I have a quick update about a previous mission. Back on NASA-5, I relayed the somewhat comical, somewhat irritating tale of the MAPS payload being delivered to Mir right as Tsibliyev, Lazutkin, and Foale were trying to deal with a major unfolding crisis. At the time I wasn’t able to determine what exactly this payload was but since Mike Foale didn’t know either I figured I’d just leave it at that. But this wasn’t good enough for podcast listener Matt H though, and he rolled up his sleeves and figured it out himself, sending me the details. It turns out that there’s a reason that MAPS sounded so familiar to me, we’ve seen it before! In fact, MAPS has been with us almost since the very beginning of the shuttle program, flying on STS-2, STS-41G, STS-59, and most recently on STS-68. The Measurement of Air Pollution from Satellites payload was dedicated to mapping out carbon monoxide levels in the lower part of Earth’s atmosphere, all across the world. Spotting carbon monoxide was a good way to spot pollution and generally anything that’s burning, so it was a helpful thing to track. Of course, MAPS never did make it outside of Mir, so I guess STS-68 was the end of the road after all. But how bizarre is it that a scientific payload on STS-2 would end up being destroyed aboard Mir as the Russian Space Station plunged through the Earth’s atmosphere 20 years later. Thanks to Matt for digging into that story and double-thanks for passing it along for all to enjoy.

Last time, we followed along on the 23rd flight of Space Shuttle Discovery as STS-85 carried out a variety of different experiments and tech demonstrations. We bid farewell to SPAS, fiddled around with a Japanese robotic arm in the payload bay, and squinted at the rapidly fading Comet Hale-Bopp. Today the only other celestial object we’ll be looking at is the Russian Space Station Mir, and it fills the view out the flight deck windows of Space Shuttle Atlantis.

That’s because today we’re heading back to the popular shuttle destination in order to retrieve Mike Foale from an eventful mission and drop off the next long haul Mir astronaut: ..Wendy Lawrence. At least, that was the plan up to about seven weeks before liftoff. Wendy Lawrence had been preparing to participate in the Mir program ever since returning to Earth on her previous flight, but right from the start there were some problems. Just days before leaving for Russia, Lawrence learned that the minimum height requirement for riding in Soyuz had been changed from 160 centimeters to 164 centimeters, or 5-foot-three to 5-foot-four-and-a-half. Lawrence was precisely 160 centimeters, so this was a problem. Rather than canceling the entire thing, Lawrence agreed to head over as NASA’s Director of Operations in Russia, helping smooth things over for the astronauts training to stay on Mir. Once over there she got to know everyone better, was measured again, and somehow this time they decided it was totally fine, no problem. She could fly on Soyuz.

But there was a wrinkle. The Sokol suit used for launch and entry in the Soyuz was one thing, but when she tried on the Orlan space suit used for extravehicular activity, the suit was far too big for her. When it was pressurized her hands couldn’t reach all the way into the gloves. So no spacewalks. But OK, no problem. She would be allowed to stay on Mir with the caveat that she would not be allowed to be perform a spacewalk.

This was fine until another problem crunched into the picture at three meters per second: Progress M-34. When the Progress resupply vehicle impacted the Spektr module of Mir, it changed the situation. Russia was determined to repair Spektr, which would require multiple difficult spacewalks. Suddenly having a member of the crew who couldn’t go outside was a liability. So less than two months before she was due to begin her Mir adventure, Wendy Lawrence was told that she couldn’t stay after all. Instead, her backup Dave Wolf would fly in her place.

You would think that Lawrence would be absolutely crushed by such a turn of events, but she seemed to take it surprisingly well. It turns out there was a reason for that. To ease the sting of having her long duration mission taken away from her, Lawrence would not only still be flying on STS-86, but was also assigned to STS-91. So before even lifting off on this mission, Lawrence had another one in the bag. Not the worst outcome, all things considered.

Another reason for Lawrence to not be crushed was that up until the day of the launch it wasn’t at all clear if Dave Wolf would even be remaining on Mir. In light of the major fire and near collision experienced by Jerry Linenger and the actual collision and depressurization experienced by Mike Foale, there were some obvious questions raised about the safety of the Mir space station. A week before the launch, NASA officials were questioned in a hearing before the House Science Committee. Congressman James Sensenbrenner started off the hearing by saying that it was prompted by a series of mistakes, accidents, systems-failures, and two life-threatening incidents, going on to say that maybe these problems should be called “Mir-haps” instead of mishaps. Pause for crickets.

The hearing went on for several hours but the gist of the Congressman’s position was this: what do long term stays on the station get us that regular resupply visits don’t? What is the scientific and technical value of having an American on Mir? And does somebody need to be killed before NASA and Russia decide that the situation is no longer safe? In making this last point, he invoked the Challenger accident, pointing out how issues with the SRB were known for years before the fatal accident but were not acted upon until disaster struck.

Just as an aside, I want to say that I disagree with Representative Sensenbrenner’s comparison here. Mir’s failures were not the same as Challenger’s. With the o-ring issue, the same problem was being observed again and again, and it was understood that if the problem progressed it would lead to a nearly instant catastrophic loss of the crew and vehicle with no recourse. Mir was experiencing a variety of different problems that while urgent, didn’t unfold on the scale of milliseconds. They could likely be addressed and if not the crew had a high probability of being able to evacuate. But let’s get back to the hearing.

The committee then invited the NASA Inspector General Roberta Gross to speak about what she had learned about the incidents on Mir. Gross brought up basically all the stuff you’d expect: hardware failures, the fire, the collision, ethylene glycol in the cabin atmosphere, CO2 levels, et cetera. Also testifying were two people who I’m sure are familiar names to many listeners of this show: James Oberg and Marcia Smith.

The main defense of the program came from Frank Culbertson. Of course, we mainly know Culbertson as the pilot of STS-38 and the commander of STS-51, but it was his role as manager of the Shuttle-Mir program that got him in the hot seat today. Culbertson talked about how the language used in the media generated mental imagery that was more extreme than the reality. For instance, when an attitude computer fails, the station doesn’t immediately spiral out of control. He even made this point with a large model of Mir, saying something like “if we were to show five minutes in five seconds, this is what the station would look like normally.. and this is what it would look like when the attitude computer failed”, and then not touching the model for either case. His point was that they’d look the same to the naked eye. I guess that’s true, and the media was painting a more dire picture than necessary, but I thought this example with the model was a little disingenuous since ok, yeah, not so bad after five minutes, but let’s see what it looks like after a couple hours.

A more salient point was that the Russian space program had a philosophy of using their components until failure. Basically, if you design your station such that any one component can fail without becoming a major safety hazard, then why would you replace stuff early? Just keep running it until it fails and then replace it. You’ll save money, better understand the capabilities and limitations of the hardware, and allow the crew to spend their time on more useful things. Of course, one catch to this approach is that someone closely following Mir’s status will observe a steady drumbeat of failures.

The upshot of this hearing was that Congress was increasingly concerned about the safety of living on Mir, and while acknowledging that it is not their call to make, strongly advised that NASA stop long duration stays on the Russian space station.

The person who did have to make the call was NASA Administrator Dan Goldin. He held off on making a final decision until almost the last possible moment. On the morning of the STS-86 launch, he held a press conference flanked by our old buddy Tom Stafford and Thomas Young, a member of the National Academy of Engineering who had performed an independent review of the decision. Goldin stated quote “It is only after carefully reviewing of the facts, thoroughly assessing the input from independent evaluators, and measuring the weighty responsibility NASA bears with putting Americans in space, that I approve the decision to continue the next phase of the Shuttle-Mir mission.” Over the course of his statement he talked about the robust safety and review processes in place, as well as the different independent groups which had agreed with the decision, including Dave Wolf himself.

I think that this was the right decision. NASA had had a wild ride on Mir over the course of 1997, but despite everything I think things weren’t quite as crazy as they looked. Personally the two things that concerned me the most were that possibility of another oxygen generator fire or the inability to start up a Soyuz without station power. The oxygen generator fire was the scariest issue, but these had been used for decades without major incident, being the primary source of oxygen for Russia’s numerous space stations. And the crew now knew to keep a close eye on them when igniting the candles. And while the Soyuz startup issue was a serious concern, it was only a concern for certain types of incidents and for a limited amount of time.

In exchange for that risk, NASA was gaining immense amounts of experience in running long duration spaceflights, and building stronger bridges between themselves and Russia. These bridges that would be critical if the ISS were to be a success. Switching to resupply missions only, or abandoning Shuttle-Mir entirely, would be a massive vote of no confidence in the skills and abilities of their Russian partners that would be difficult to return from. In NASA’s view, just like how Mercury and Gemini were proving grounds for Apollo, Shuttle-Mir was the proving ground for the ISS. The mission would proceed. Let’s find out who’s flying it.

Commanding this mission was a familiar face: Jim Wetherbee. We’ve seen Wetherbee a number of times already, most recently when he commanded STS-63, the Near Mir flight. Today he’ll be closing the final few meters to the station for docking on this, his fourth of six flights.

Joining Wetherbee up front was today’s pilot and lone rookie for this mission, Mike Bloomfield. Michael Bloomfield was born on March 16th 1959 in Flint, Michigan, growing up just down the road in Lake Fenton, Michigan. He earned a Bachelor’s in Engineering Mechanics from the US Air Force Academy and later down the road picked up a Master’s in Engineering Management from Old Dominion University. In between those two degrees he reported to Vance Air Force Base and learned how to fly the F-15. He served as a combat pilot and instructor pilot for eight years before graduating from the US Air Force Test Pilot School, becoming a test pilot for the F-16. He was selected as an astronaut in 1994 and this is his first of three flights.

Moving back in the flight deck we find Mission Specialist 1 Vladimir Titov. Titov is a cosmonaut whose first two flights were on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft, but he’s also flown on the shuttle before, joining Commander Wetherbee on STS-63 just a few years back. This is his fourth and final mission.

Next to Titov was Mission Specialist 2, Scott Parazynski. We know Parazynski from his first flight, STS-66, which flew the ATLAS-3 payload and also deployed and retrieved the first iteration of the CRISTA-SPAS payload. This is his second of five flights.

Moving downstairs, we meet Mission Specialist 3, Jean-Loup Chretien. This is actually Chretien’s third flight into space, but it’s his first with us, so we’ll do a quick bio. Jean-Loup Chretien was born on August 20th, 1938 in La Rochelle, France. And settle down, Star Trek fans, that’s Jean-Loup, not Jean-Luc. He graduated from the –oh boy– Coo-LEIGE San Sharl a San Bree-yuu and then the French Air Force Academy, earning a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the latter. The French Air Force taught him how to fly fighter jets and that’s what he did for the next 18 years or so, serving in a variety of roles on a variety of aircraft, including supervising the flight test program for the Mirage F-1 fighter. In 1979 France and the Soviet Union agreed to fly a French cosmonaut on a future Soviet flight and the next year Chretien was selected as one of two finalists. A year after that he began training for his first mission and a year after that launched on Soyuz T-6, docking with Salyut 7, the predecessor to Mir, making him the first French person to fly in space. Six years later he returned to space, spending 22 days on Mir and even performing an EVA. With that EVA he became the first person who wasn’t American or Russian to walk in space. This is his third and final flight.

Joining Chretien on the middeck was Mission Specialist 4, Wendy Lawrence. We know Lawrence from the second flight of the ASTRO payload, flying on Space Shuttle Endeavour on STS-67. She may not be remaining on Mir as expected on this flight, but her training would not go to waste, as she put her expertise to use helping to set Dave Wolf up for success as he flew in her place.

And finally we arrive at Mission Specialist 5, Dave Wolf, the only member of the crew who won’t be returning to Earth at the end of this flight. When we last saw Wolf, he was flying on STS-58, the Space Life Sciences 2 flight, with two other Mir long haulers: John Blaha and Shannon Lucid. When looking at the trouble experienced by Linenger and Foale on their stints, the thought that he might be getting more than he bargained for with this mission must have crossed Wolf’s mind at some point. But when asked about it he said quote “It’s easy to be good partners with the Russians when things are going easy, but it’s when things are difficult that we really can show what good partners we will be.” This is Wolf’s second of four flights.

After all the debate about the state of the Shuttle-Mir program, the launch finally occurred right on schedule on September 25th, 1997, at 10:34 PM Eastern Daylight Time, with no unplanned holds. After an uneventful ascent and far field rendezvous, Mir was soon a bright point on the horizon.

Today’s rendezvous would be notable since it was the first to use an optimized version of the R-bar approach that we’re already familiar with. Appropriately enough, the new technique was called the Optimized R-bar Targeted Rendezvous or ORBT. The last phase of rendezvous begins with the Terminal Insertion, or Ti, burn. This is typically done around 15 kilometers behind the rendezvous target while at the same altitude. Once performed, the shuttle would dip down below the altitude of the target, which of course meant that it moved faster in its orbit, which meant that it would catch up with the target. After half a trip around the world it would reach the new low point of its orbit and start moving back up. Assuming the flight dynamics team on the ground did their math right, the shuttle then comes rising up right to the place where the target is. At least, that was the old way of doing it, the so called Stable Orbit Rendezvous. This wasn’t great because we don’t actually want to come swooping directly up to Mir, we want to arrive on the R-bar and sort of slowly nudge our way up. With a Stable Orbit Rendezvous, extra burns are required to deviate from the path the orbiter would be on and instead arrive on the R-bar.

With this new Optimized approach, the shuttle basically missed on purpose. Instead of the target point being Mir itself, it was a position underneath Mir on its R-bar, doing away with the need for some of the correction burns. Further optimizing the approach, the Ti burn was performed while slightly below the V-bar. This is really getting into the weeds, but by doing this burn lower, it meant that the MC4 midcourse correction burn could mostly be done along the orbiter’s +X axis. In other words, just by thrusting forwards. I believe that this was taking advantage of the timing of the final parts of the rendezvous and the attitude the shuttle would be in at that time, such that it could use more efficient thrusters as opposed to something like the inefficient Low-Z mode we’ve discussed in earlier episodes. This slight tweak to the approach could save almost 100 kilograms of propellant, so it was worth the effort. In fact, this is how all R-bar approaches will be performed for the remainder of the shuttle program. Commander Wetherbee and Pilot Bloomfield, with the rest of the crew assisting, executed this new approach with no issues, docking with Mir about 41 hours after lifting off.

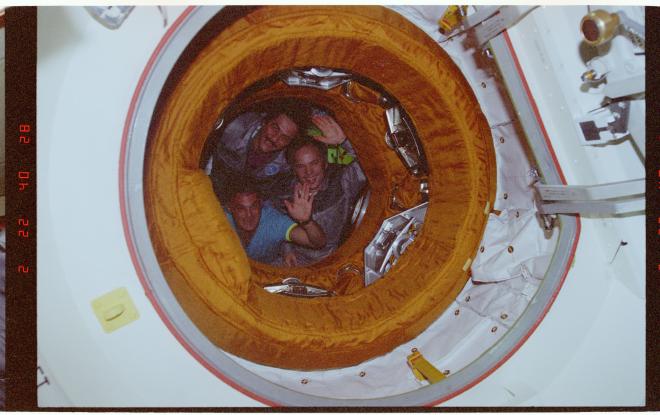

One of Mir’s most pressing issues these days was an ailing attitude control computer. In an all too frequent annoyance for the crew, and apparently Congress, the computer would occasionally crash, leading to Mir drifting out of its nominal attitude and power being lost. Russia already had a replacement computer packed onto an upcoming Progress resupply ship, but also provided one for the shuttle crew to bring up with them. Originally it was slated to be transferred over to the station on the second day of docked operations, but Mir commander Solovyev had requested that they bring it over after the welcoming ceremony on docking day. Deciding to take things even further, when Commander Wetherbee and Commander Solovyev shook hands across the hatch, Wetherbee was holding the new computer in his other hand and was able to deliver it immediately. How’s that for service?

The shuttle’s arrival meant that the new computer was available, but it also meant that when the swap actually happened a few days later it was much easier. With the shuttle handling attitude control for the entire docked structure, the Mir crew were able to replace the computer without having to worry about aimless drifting.

As usual, the next few days were a flurry of activity as the combined crew moved thousands of kilograms of equipment, clothing, food, science experiments, and water between the two vehicles, and finding places to store all of it. Wendy Lawrence would no longer be remaining behind for the long haul, but still had an integral role to play during docked operations. Since until recently she had expected to be running these experiments and Dave Wolf had, well, not, Lawrence zipped around getting everything set up for Wolf. Her assistance in this first part of the mission ensured that Wolf could hit the ground running, or I guess floating, and not waste precious time just trying to set up the basics. It also allowed him to spend more time with Foale, learning how life on Mir actually worked.

While Lawrence and Wolf scurry around inside getting set up for the months to come, we get to turn our attention outside for a significant milestone in spaceflight history. When Scott Parazynski emerged for the mission’s lone EVA, he was soon joined by Vladimir Titov, making this the first time that a non-American has performed a spacewalk for an American mission. The duo immediately got to work, traversing over to the Docking Module. The main goal of this EVA was to retrieve the Mir Environmental Effects Payload, or MEEP, which remains a fun word to say. MEEP was one of these experiments that falls into the category of “let’s just stick some stuff in space for a while.” Specifically, the goal was to stick a bunch of materials that might be used for the ISS in space for a while so if there were any major issues they could be caught before NASA was committed to them. It was an especially good test because Mir was in a very similar orbit to the one that was planned for the ISS, so the MEEP results should be representative of what to expect.

MEEP had been placed there back on STS-76 when Linda Godwin and Rich Clifford became the first Americans to climb around outside Mir. After a year and a half of waiting, it was time to come back inside. Parazynski said that the operation was surprisingly delicate since both he and Titov had to be extremely mindful of the position of their bodies and tethers as they approached the payload. One errant touch from their equipment could contaminate the samples and invalidate the results. But with a little extra care, the experiments were retrieved and stowed in the orbiter payload bay without incident.

While they were on the Docking Module, they also attached a heavy metal cap to its exterior for safekeeping. The cap was hopefully going to be used on a future Russian spacewalk to seal the leak on Spektr. The tentative plan was that if the leak was indeed where the damaged solar array connected to the module, the solar array could be jettisoned and then this cap could be fit over its connection. The cap was delivered by Atlantis because it was actually too big to be deployed from Mir.

Another task performed while outside was an evaluation of the production version of the SAFER jetpack. As you’ll recall, SAFER, or “Simplified Aid For EVA Rescue” was sort of a slimmed down version of the old Manned Maneuvering Unit jetpack that could be bolted onto a spacewalker’s life support backpack. With so many EVAs expected for space station construction, SAFER provided spacewalkers with the ability to rescue themselves if they became disconnected from the station structure. Theoretically the shuttle could undock and retrieve them, but as we’ve learned, undocking isn’t something that can be done quickly and with little warning, and rendezvousing with a stranded astronaut who departed in a random direction with a random delta-v and with a multi-hour head start would not be trivial. Instead, a stranded astronaut could pull a lanyard down, gaining access to the SAFER controls. Operating the controls would fire little nitrogen gas thrusters and allow the astronaut to control their attitude and putt-putt back over to the station. When it was first tested, back on STS-64, it was the last untethered spacewalk of the shuttle program.

Rather than risk an untethered EVA this time, Parazynski and Titov remained firmly attached to a foot restraint as they tested the apparatus. Parazynski reported being able to hear the tiny thrusters firing but felt no movement pushing him around. Which makes sense, it doesn’t take much to gently push a person around in weightlessness, so it’s not like the thrusters needed to be strong enough to knock him around. SAFER worked as expected and would become a staple for ISS spacewalks.

After 5 hours and 1 minute outside, Parazynski and Titov were back inside, and the 39th spacewalk of the shuttle program was complete.

As docked operations wrapped up, Wendy Lawrence said goodbye to Mir for now, Mike Foale said goodbye to Mir forever, and Dave Wolf said goodbye to Space Shuttle Atlantis. With the hatch sealed up, the pilot crew retracted the latches on the Orbiter Docking System, fired the Low-Z thrusters, and gently backed away. Once at a safe distance, Wetherbee handed controls over to rookie pilot Bloomfield, which is a pretty nice thing for a shuttle commander to do.

First on the agenda was to back away in stages, similar to what had been done last time we left Mir, and for the exact same reason. The European Space Agency was hard at work developing the Automated Transfer Vehicle, their own space station resupply spacecraft, and it was critical that its range sensors work properly. Using Atlantis as a stand-in for the ATV and Mir as a stand-in for the ISS was a perfect way to see how it performed in real world conditions. As Atlantis backed away to a distance of 180 meters the sensor did just fine, and once its evaluation was complete, unlike last time, Atlantis moved back in, re-approaching Mir. As Atlantis gently flew around the station at a distance of 60 meters and both crews snapped photos of the others’ vehicles through the windows, there was one more test to perform. When Atlantis was positioned such that it had a good view of the battered solar array on Spektr, the Mir crew opened some valves and allowed a small amount of air to enter the depressurized module. The hope was that when the small amount of air leaked through the damaged hull, it would make some sort of visible disruption. Maybe it’d be some ice crystals or maybe some debris could kick loose, who knows. But if the shuttle crew could spot stuff streaming out of Spektr the leak could possibly be pinpointed and repaired.

The leak test was a good idea, but it didn’t work out quite as well as was hoped. At first there was indeed a stream of particles visible coming from somewhere near the base of the solar array, but the stream soon stopped and was wasn’t enough to see exactly where the particles came from. They tried a second pulse of air but barely anything resulted from the second attempt. The site of the leak remained elusive.

After the flyaround was complete, Atlantis again fired its RCS thrusters and Mir was soon once again nothing more than a distant point of light. The crew were treated to an extra day on orbit when two attempted landings at the Kennedy Space Center were called off, but the next day it turned out that the third time’s the charm. After cruising through an uneventful reentry, Atlantis touched down at the Shuttle Landing Facility rolling to a stop and closing out a mission lasting 10 days, 19 hours, 20 minutes, and 53 seconds.

With this flight, the budding relationship between NASA and their Russian counterparts had survived a serious test and the partnership carried on. With the Atlantis crew back home, all eyes turned to Dave Wolf and his Russian crewmates for what everyone hoped would be a nice, boring, productive and uneventful flight.

Next time.. I usually avoid including scheduling notes on the podcast since a lot of people listen to the show years after the fact. But considering that a) the next episode will cover Dave Wolf’s flight on NASA-6, b) my track record for delivering Mir episodes on time is terrible and c) Saturnalia (and the resulting holiday travel) is upon us, don’t be surprised if I slip the episode by a week or so. But it’ll be worth the wait because next time.. Dave Wolf is in for a nasty surprise at the end of his first spacewalk, when he discovers why Mir has a backup airlock.

Ad Astra, catch you on the next pass.